In Passing

Nicole Coson

Silverlens, New York

About

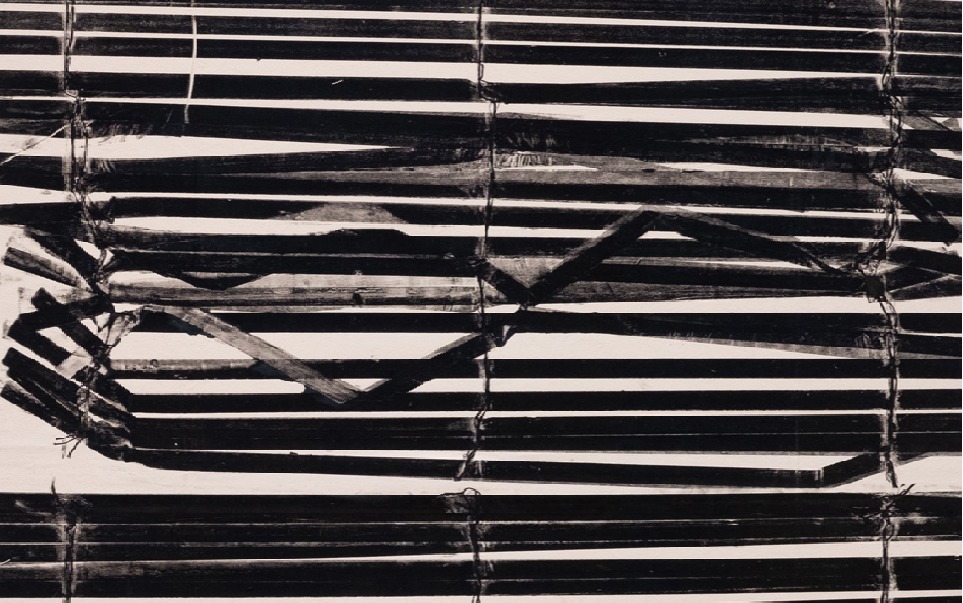

London-based artist Nicole Coson (b. 1992, Manila, Philippines) debuts her New York solo show, In Passing. For Coson, repetition and seriality are conceptual matrixes for questioning the durability of traces across geographies and time. Over the last decade, the artist has expanded printmaking’s limits, deepening its material registration logic by incorporating everyday household items into the traditional press. Through the exhaustive repetition of seemingly cordoned-off or non-signifying surfaces (camouflage textile, window blinds), Coson’s work quietly allows for an appreciation of diasporic identity through allegories of infrastructure and material culture.

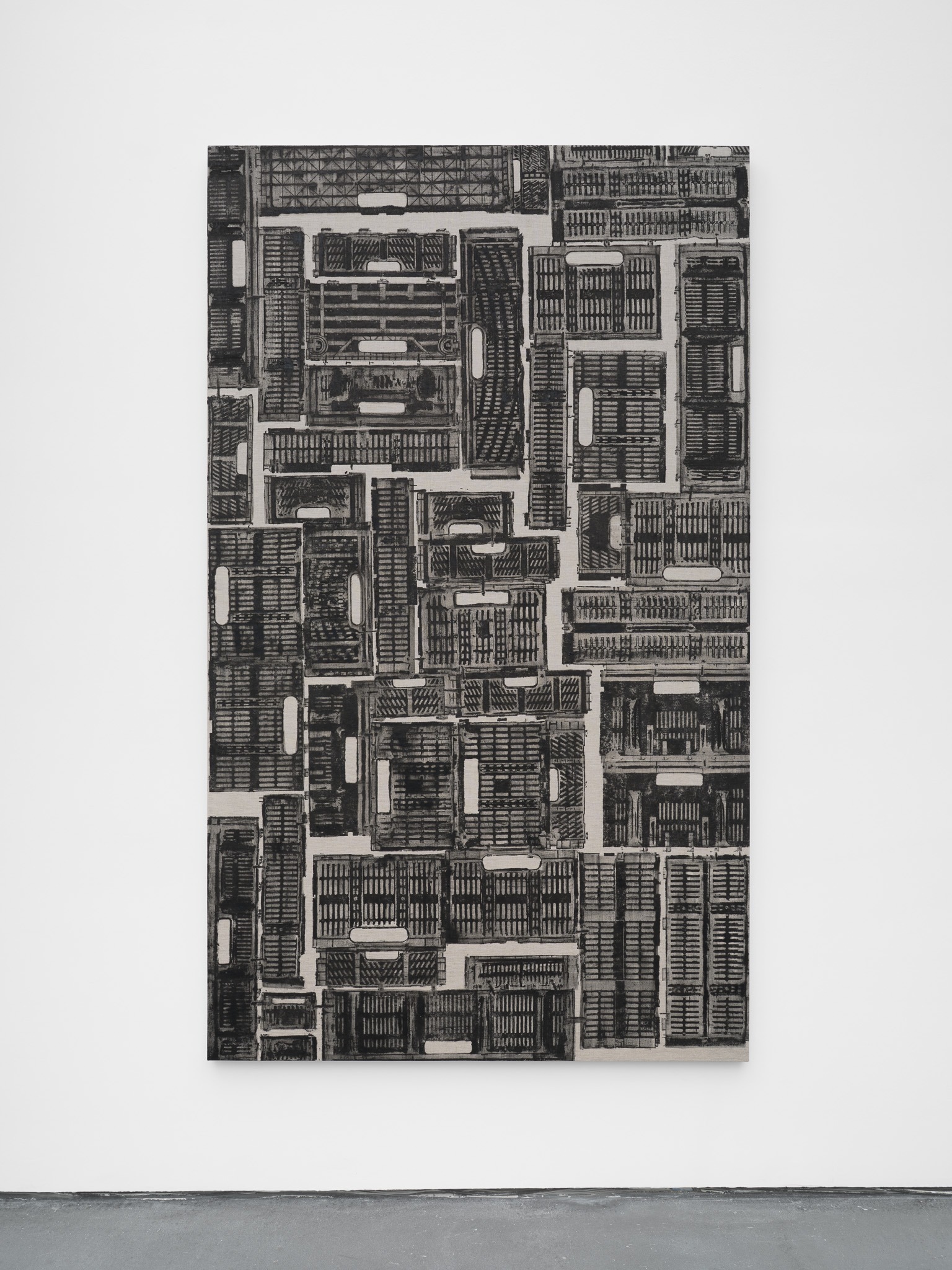

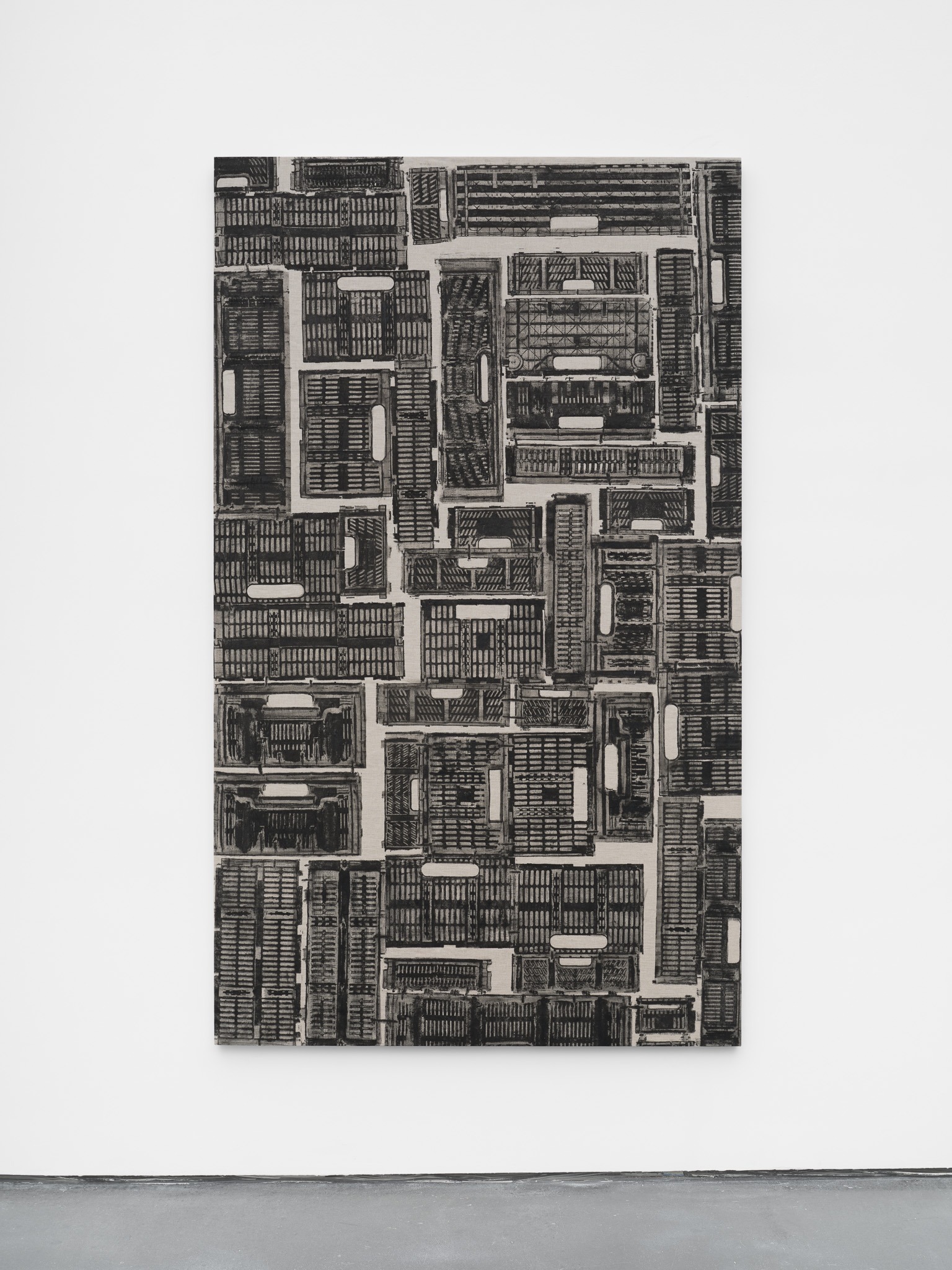

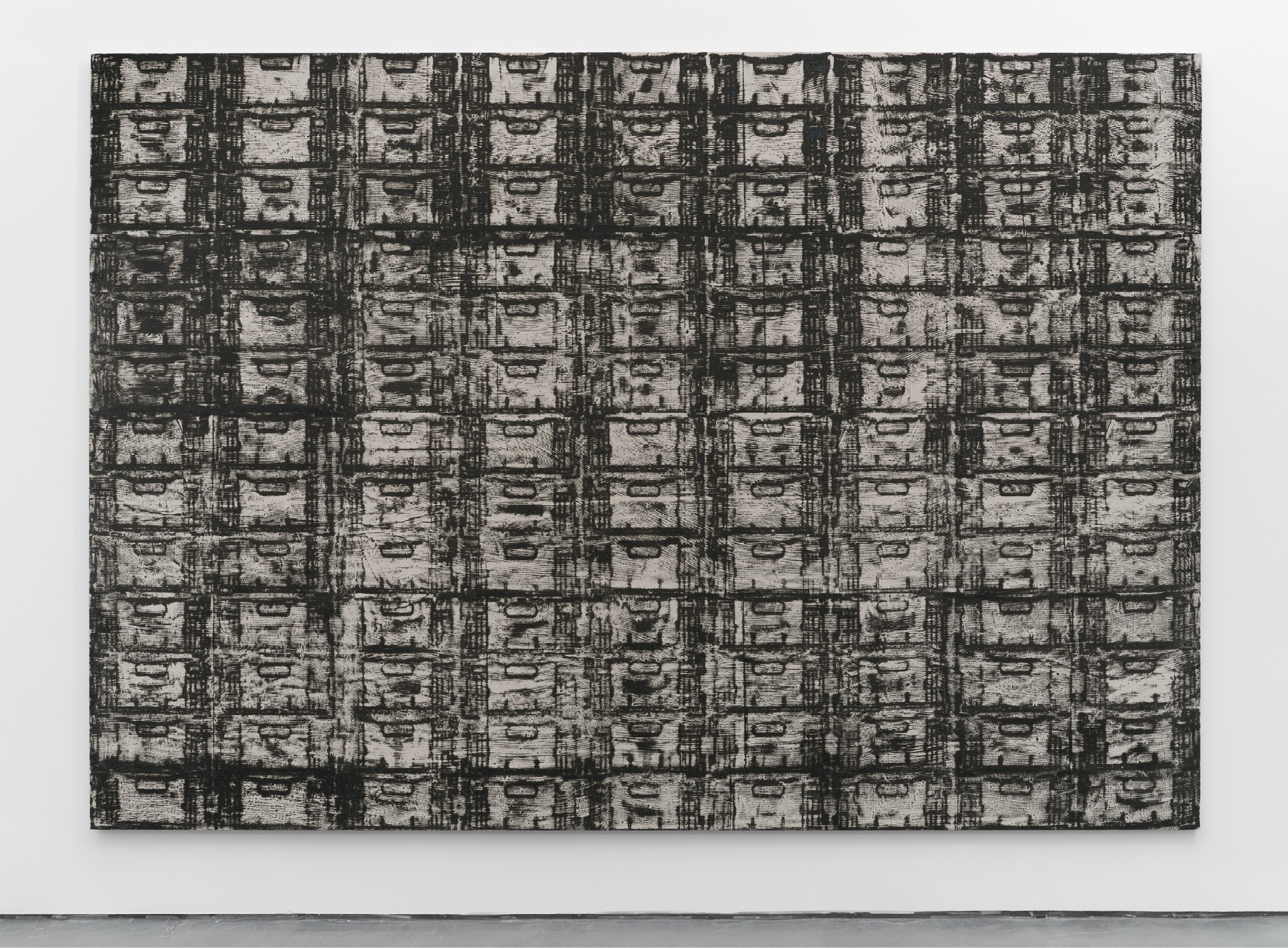

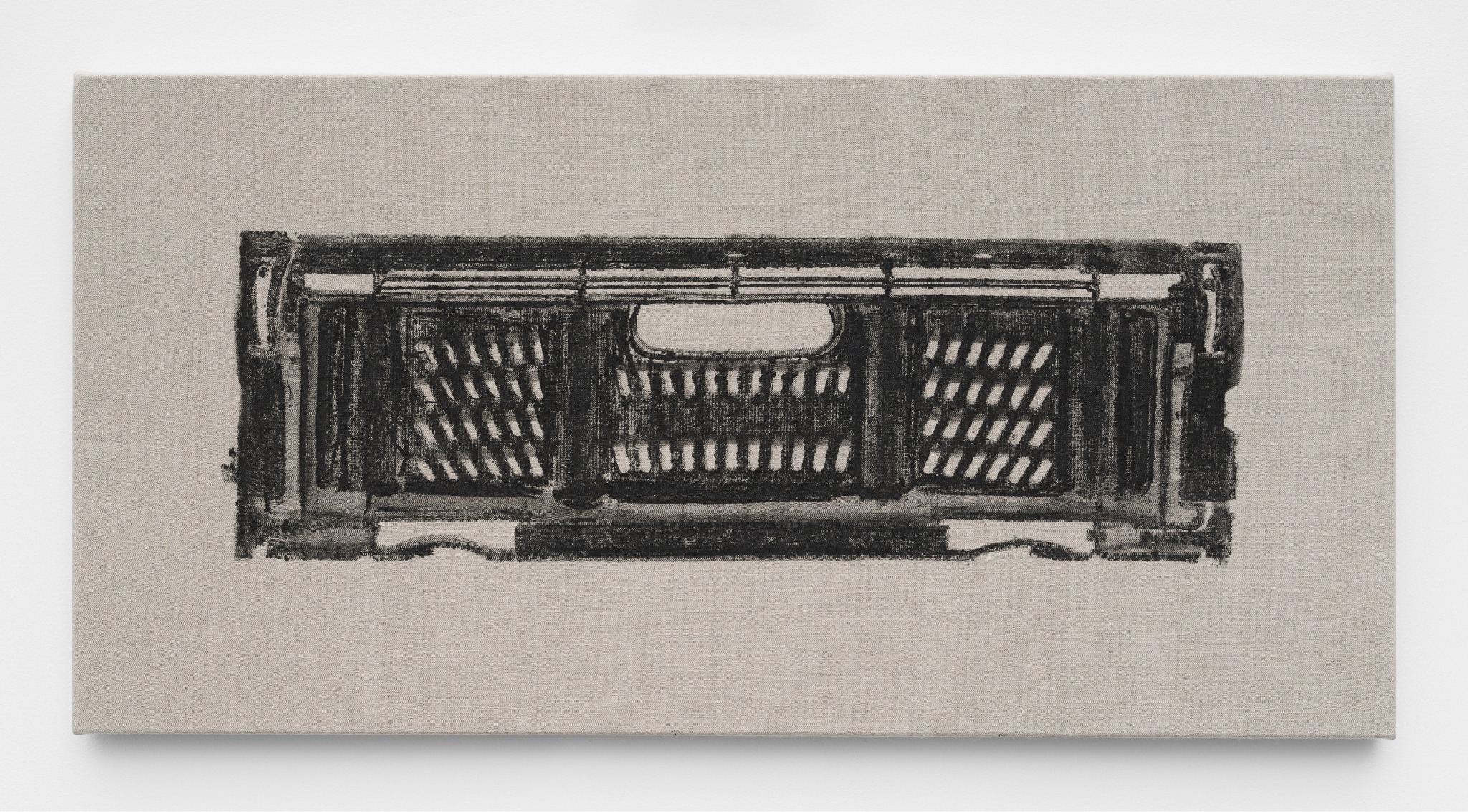

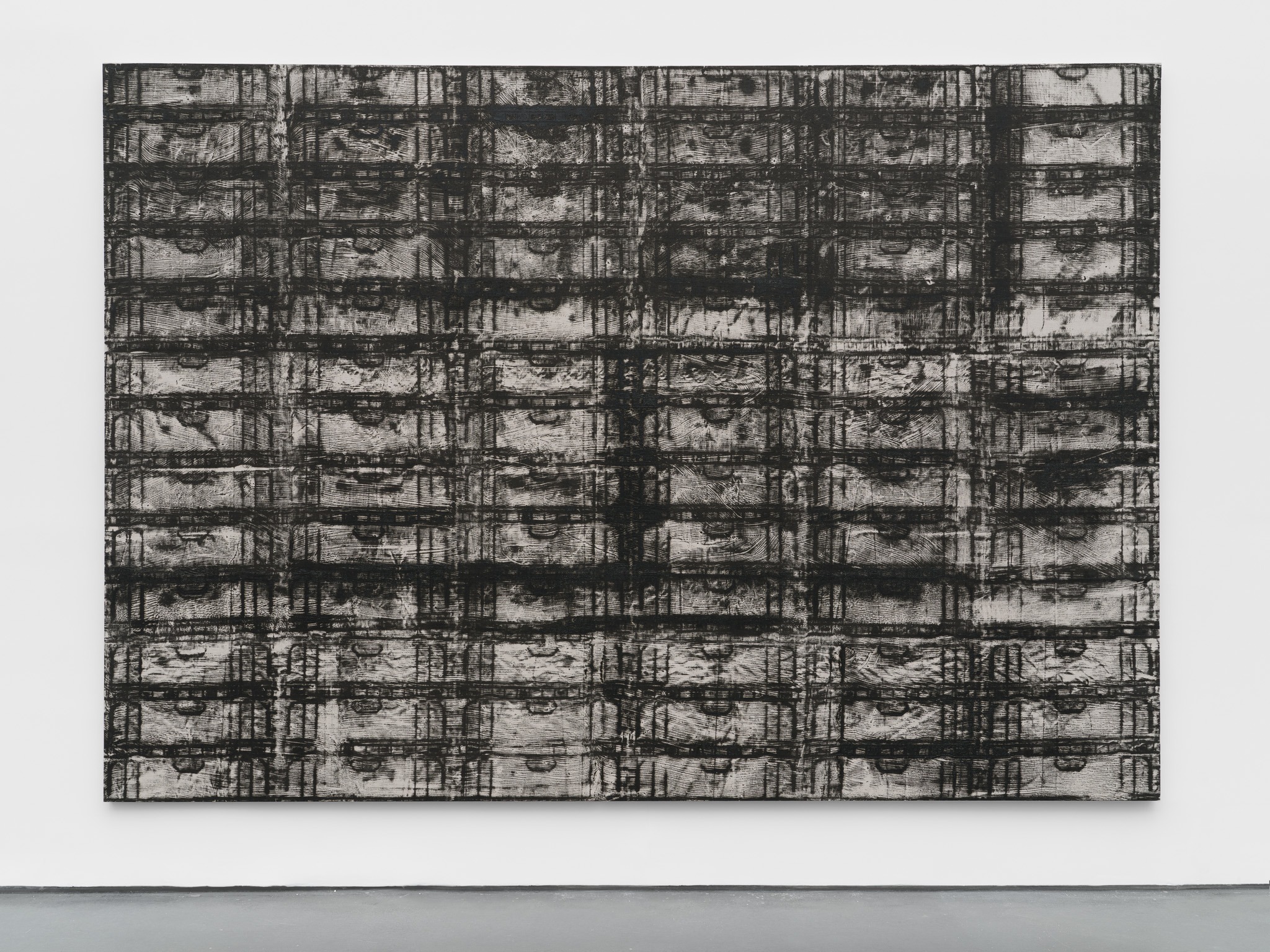

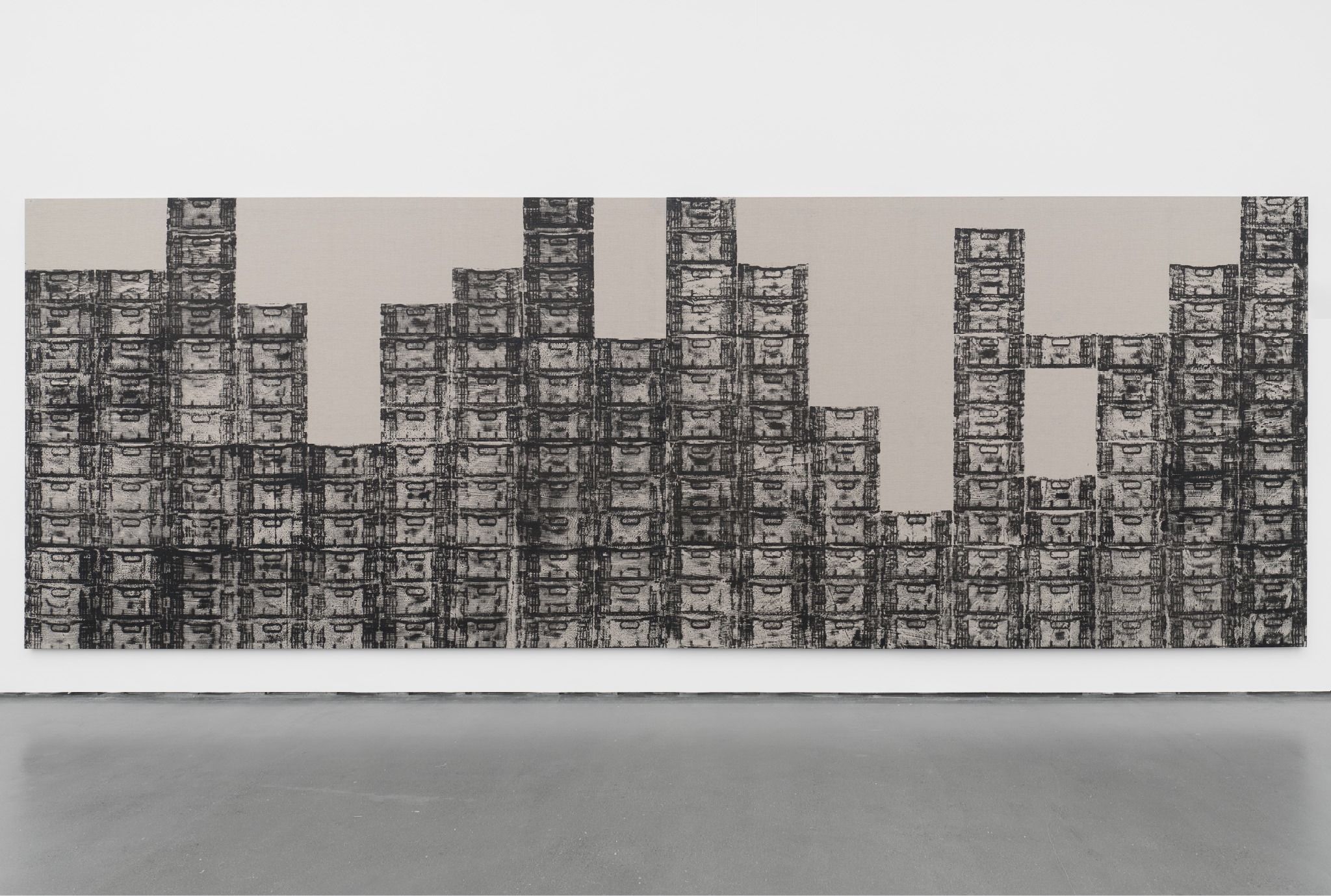

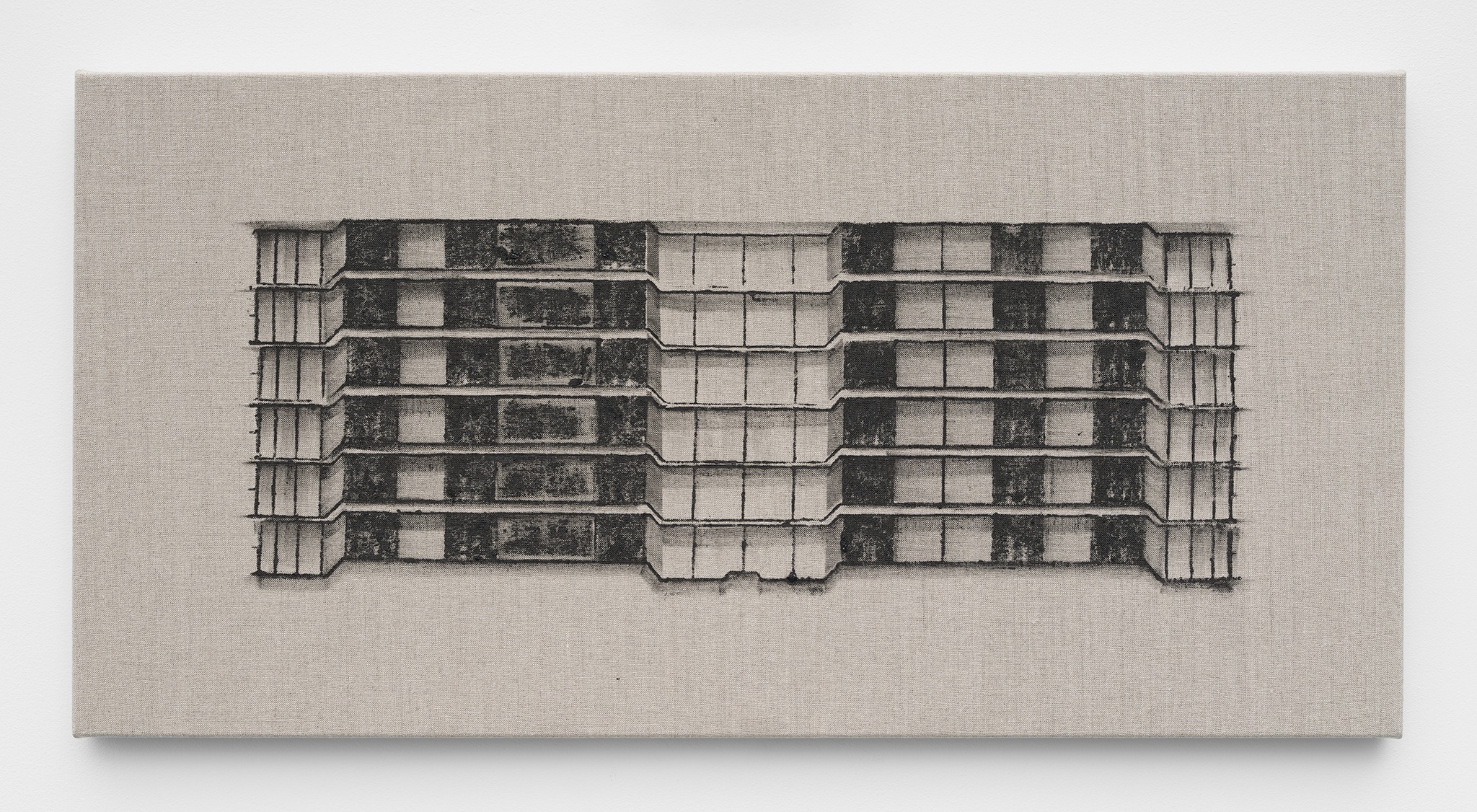

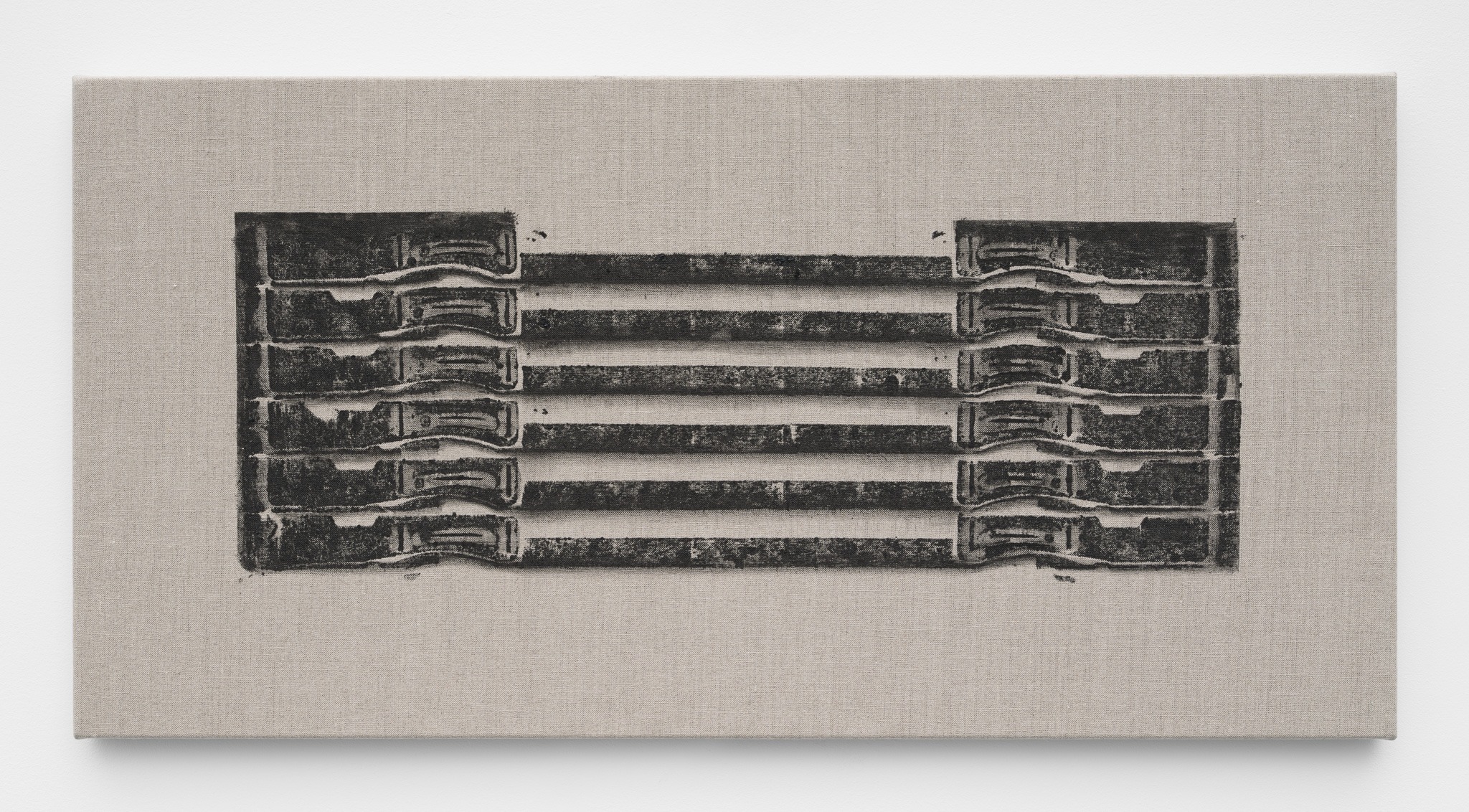

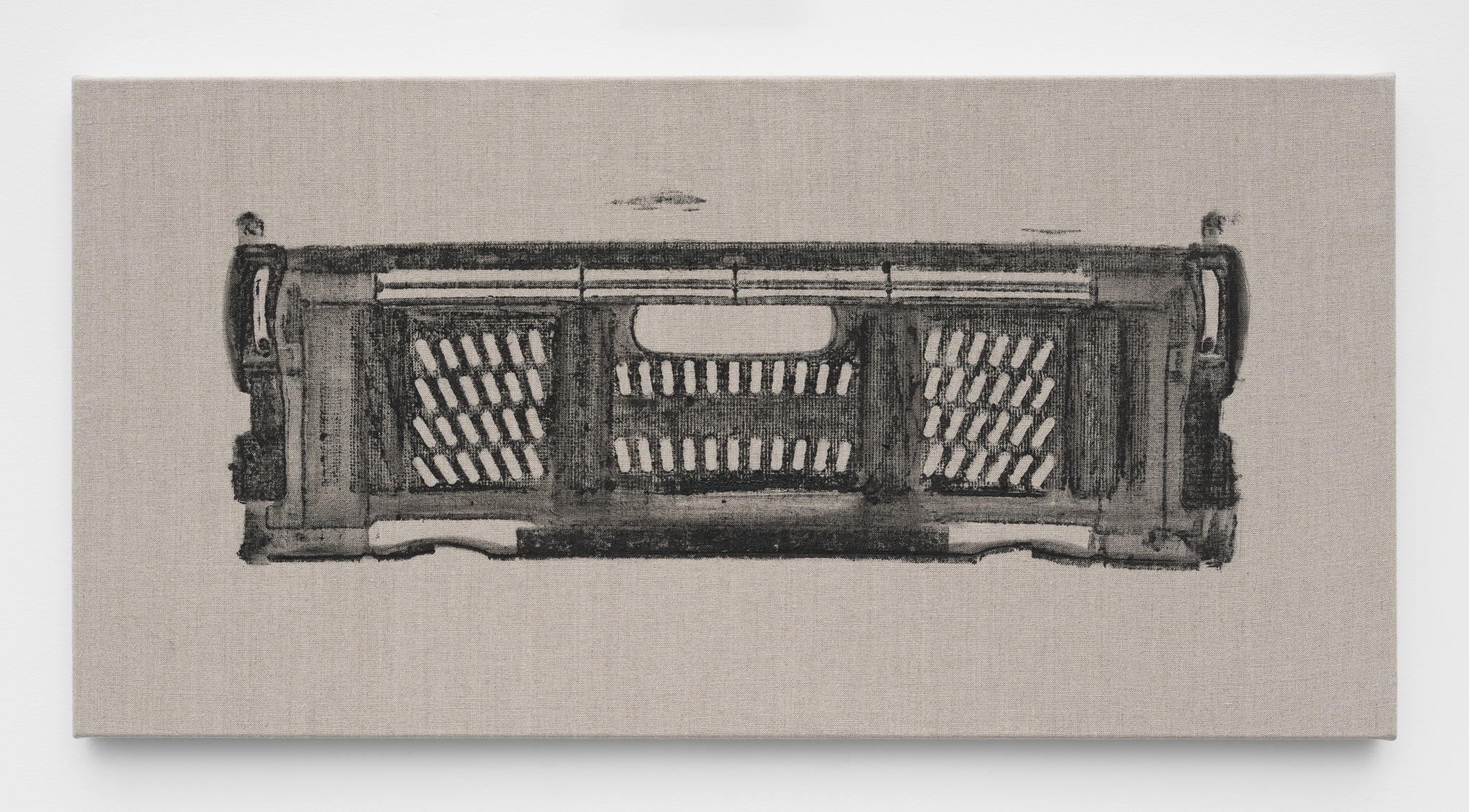

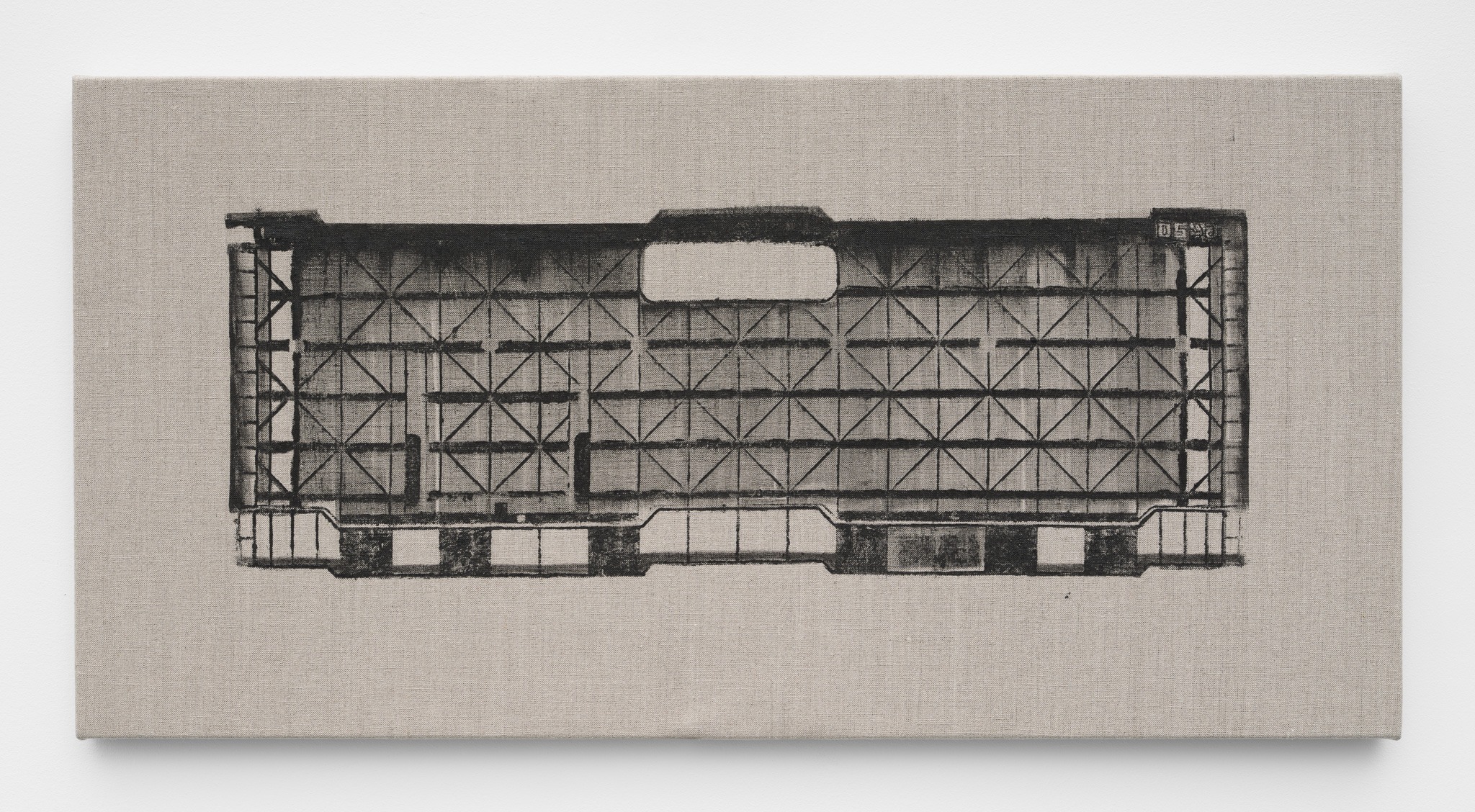

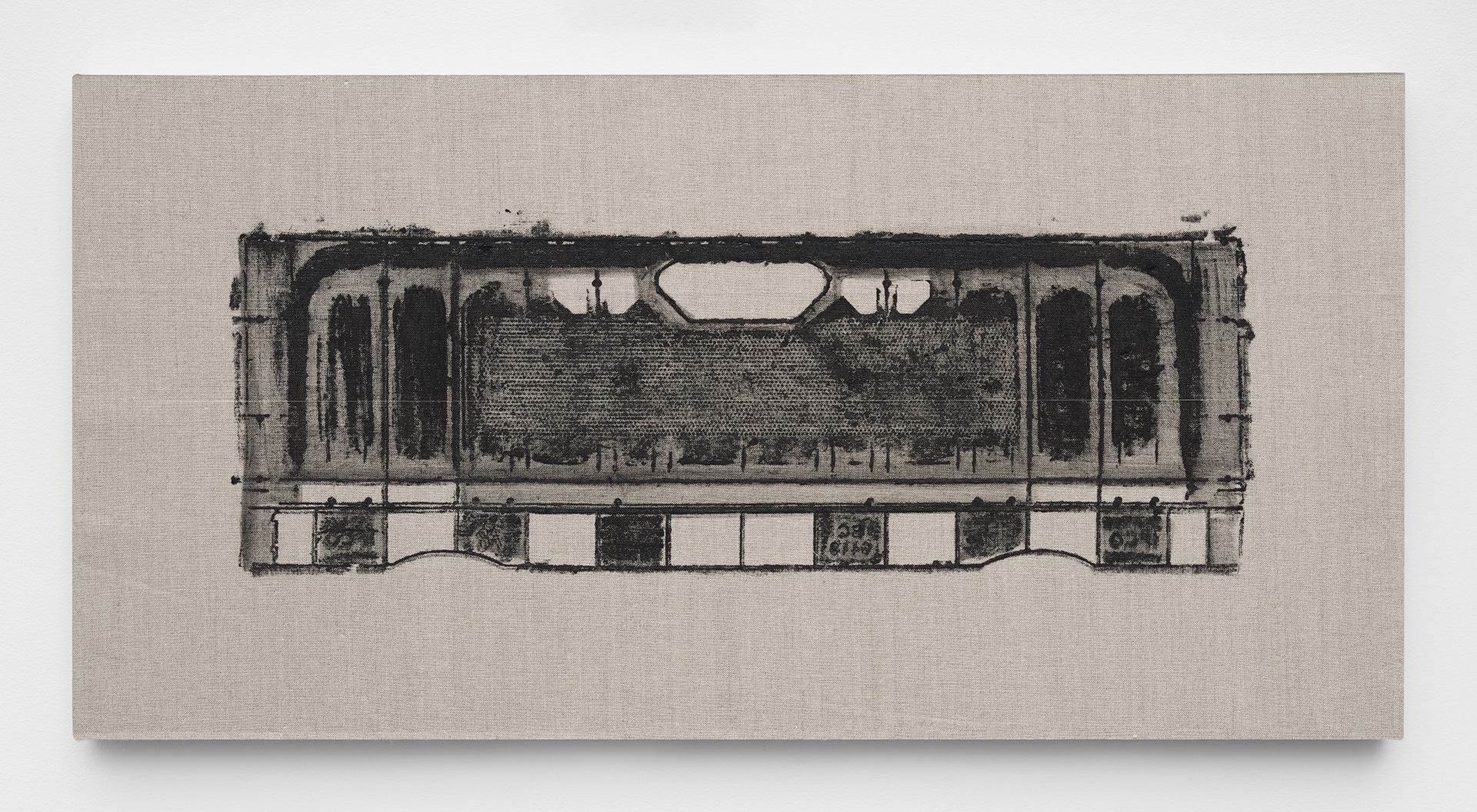

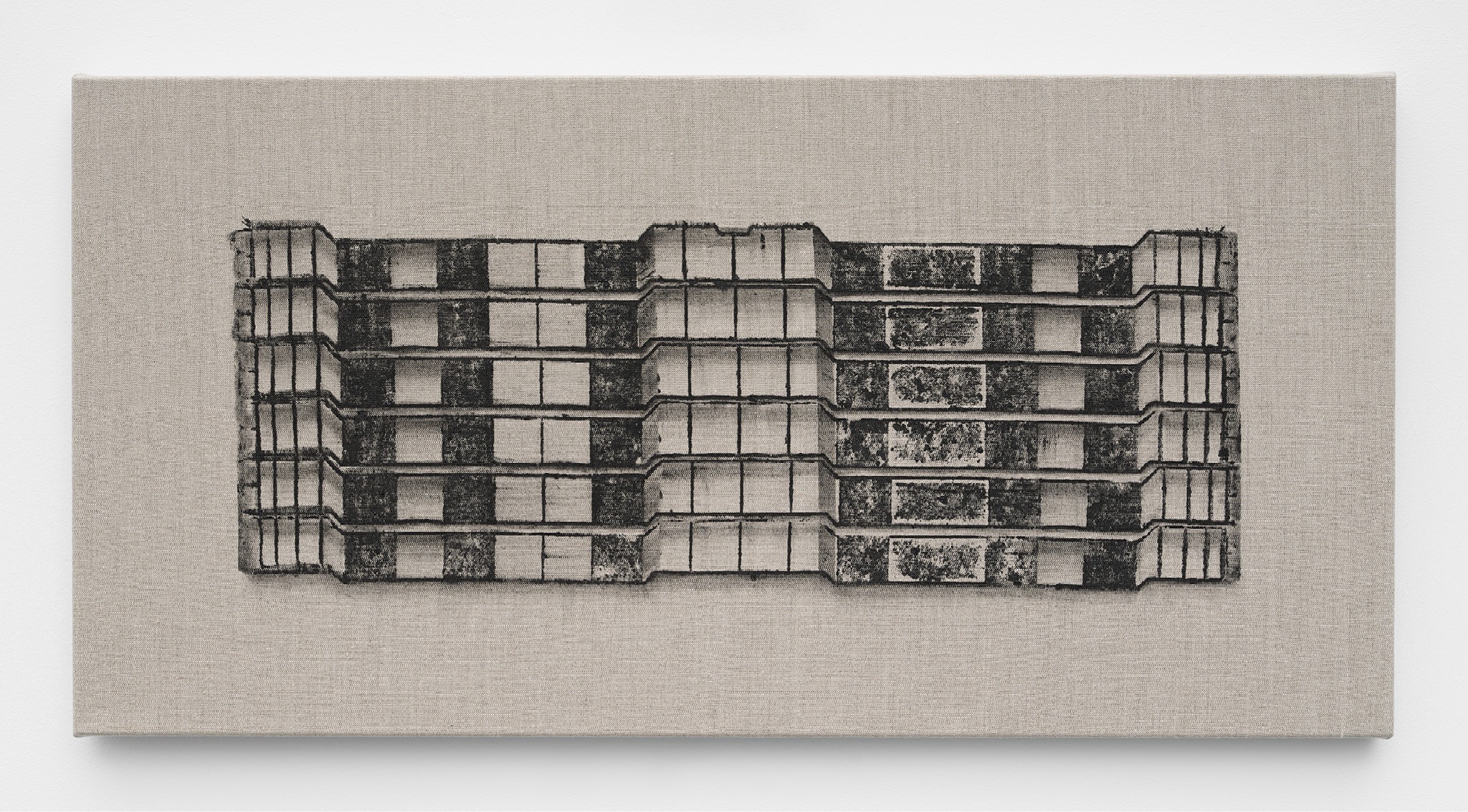

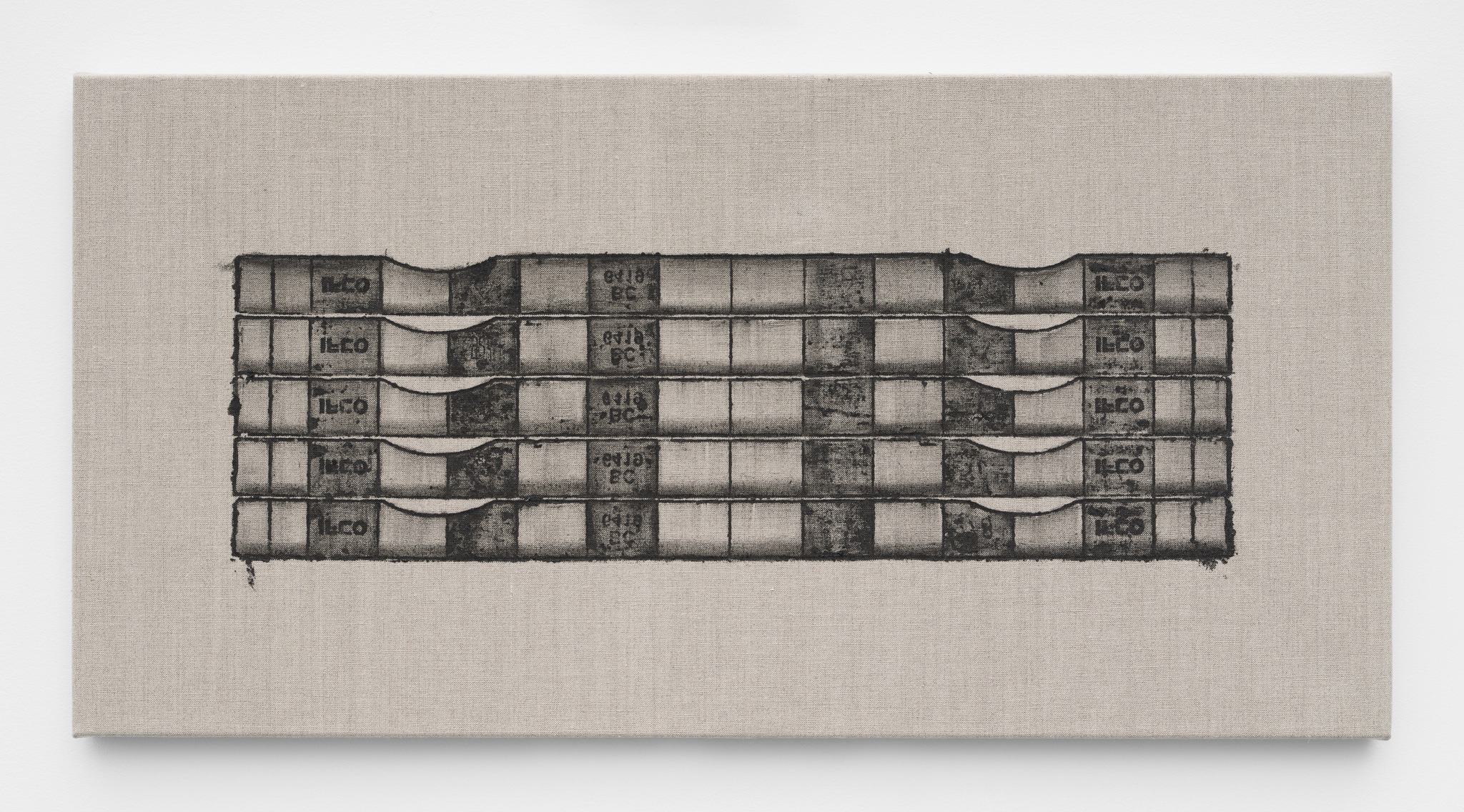

In the exhibition In Passing, Coson’s starting point is the standard plastic shipping crate, used ubiquitously in the global supply chain for food and other perishable goods. The most standardized of designed forms, these crates’ cubic, stackable anatomy is materially analogous to the serial logic of the print—manufactured objects predicated on the totalizing logic of sameness.

Yet, as Coson’s work shows, both object systems are distinctive for their undeniable heterogeneity and deviance from any given “model:” Each crate (around 20 were used by the artist) is unique in its wear, just as all prints boast their own delicious imperfections caused by the inevitable contingencies of ink, paper, and press. What crystallizes in the artist’s approach is the aesthetics of contingency itself, its narrative potential, and socio-economic resonances.

In the front area and first gallery, imprints of various crates are arranged densely side by side across a canvas. They resemble circuit boards or aerial views of cities, the negative space between each mark suggesting roads, alleyways, passages. The artist resumes this logic in the main gallery but in a cross-view, to a very different effect: the crates now suggest dense cityscapes. These Tetris-like verticalities resemble the concrete building blocks that make up the pre-fab stories of highrises. In both series, the totalizing modularity of the crate design analogizes city planning, but only in its emphasis on inherent imperfection and variability. Behind the modularity of mass-industrial modernism—an aesthetic program violently spread across the vastness of the world in the 20th century—you can find, still, endless dimensions of difference, birthed not from design but from the idiosyncrasies of (mis)use, inhabitation, and customization.

Coson’s canvases are invitations to linger in these urban materialities, which inevitably points to the lived lives of its denizens. Just as the density of cities is an endless source of storytelling, one can get lost pondering the origin of the objects that journey across the global supply chain, its people, and its commodities forever on the move.

Yet origin, devastatingly, will only ever reveal itself in riddle-like fractures. Crates are themselves without a home but instead destined for endless transit—forever clicking into one another in new dizzying con-figurations. What they have held and carried remains a potent mystery, legible only in ghostly traces on its surfaces—mark-making, as it were. This, Coson shows us, is the groundwork of poetic fabulation, which is still more than possible in the infrastructural reality of the 21st century.

The artist’s self-devised crate printing crates—which, in the artist’s own words, is “hardly printmaking at this point”—stretches traditional techniques of indexical registration onto canvas into an uncertain realm of material confrontation, negotiation, and gesture. The physical application of ink at this scale allows (in fact demands) the transfer of gestural marks: the result is something akin to woodgrain or fingerprints that, upon closer look, breaks up the seriality of the motif. Here, Coson’s aesthetic of anonymity probes the logic of painting, its so-called “vitality,” referencing a once-present body of an artist in front of a canvas.

Installed centrally in the exhibition space is Some place, within here, a towering, cubic installation featuring aluminum-cast Aklan oyster shells threaded between interlocking metal loops hanging from the ceiling. The work explicitly mimics the spontaneous structures used to aquafarmed oysters in Aklan, a Visayan province in the Philippines, where these mollusks are cultivated on bamboo grids, dangling beneath the ocean’s surface. As they age, the traces of aquatic and temporal differences in the undercurrent are imprinted on rings in their shells. In bringing this spatial arrangement to the far-flung white cube spaces of Chelsea, New York City, it may take on the formal similitude to the language of post-minimalism, or even more specifically, Felix Gonzales Torres’ famous strung-together lightbulbs in his 1992 work Untitled (1992). Here again, one place’s material culture finds a new semantic possibility in its movement through contexts; the common oyster farm is confused for something monumental, and by taking the place of the artwork, calls attention to the processes and politics of sculptural reification.

For Coson, the medium of printmaking—that noble art of seamless seriality—is uniquely predisposed to understand systems through their irregularities in both logistical and pictorial terms; that they, in fact, invite us to speculate obscure biographies in the traces of physical impression. This is also the rich context of understanding diaspora, which so often can only be measured in what is brought with, carried, lost, or shipped to a “home” or “homeland” somewhere.

– Jeppe Ugelvig

Nicole Coson (b. 1992, Manila) is a Filipino artist based in London. She holds an MFA in Painting from the Royal College of Art London. Working in printmaking, painting and sculpture, Coson’s work explores the process of image-making as it pertains to personal memory, history, and material culture. Coson’s printed canvases oscillate delicately between surface and depth: by integrating symbolically-loaded found objects into the etching press, concrete material culture transforms into analog, indexical images through their negative imprint. This imagistic oscillation between pattern, image, and object is embraced by Coson to tell stories of family, society, and coloniality, but never in straight-forward ways: rather, the artist is deeply committed to the aesthetic politics of opacity and by extension, privacy, secrecy, and intimacy. Rather than alluding to a hidden meaning behind her barrier motifs (camouflage patterns, window blinds, woven baskets, food crates), Coson invites us to study them as such—barriers—and the critical potential of visual obfuscation.

Coson’s work on canvas is supplemented by occasional culinary and publishing projects, such as the ongoing Food Stories: The Silkroad (2018), where food is explored as a palimpsest of migration histories—of people, spices, and recipes. Coson was featured in Bloomberg New Contemporaries in 2020, and has since held solo exhibitions at Silverlens in Manila, Philippines and Ben Hunter Gallery in London, UK.

Installation views

Works