Rigodon

Imelda Cajipe Endaya

Silverlens, Manila

About

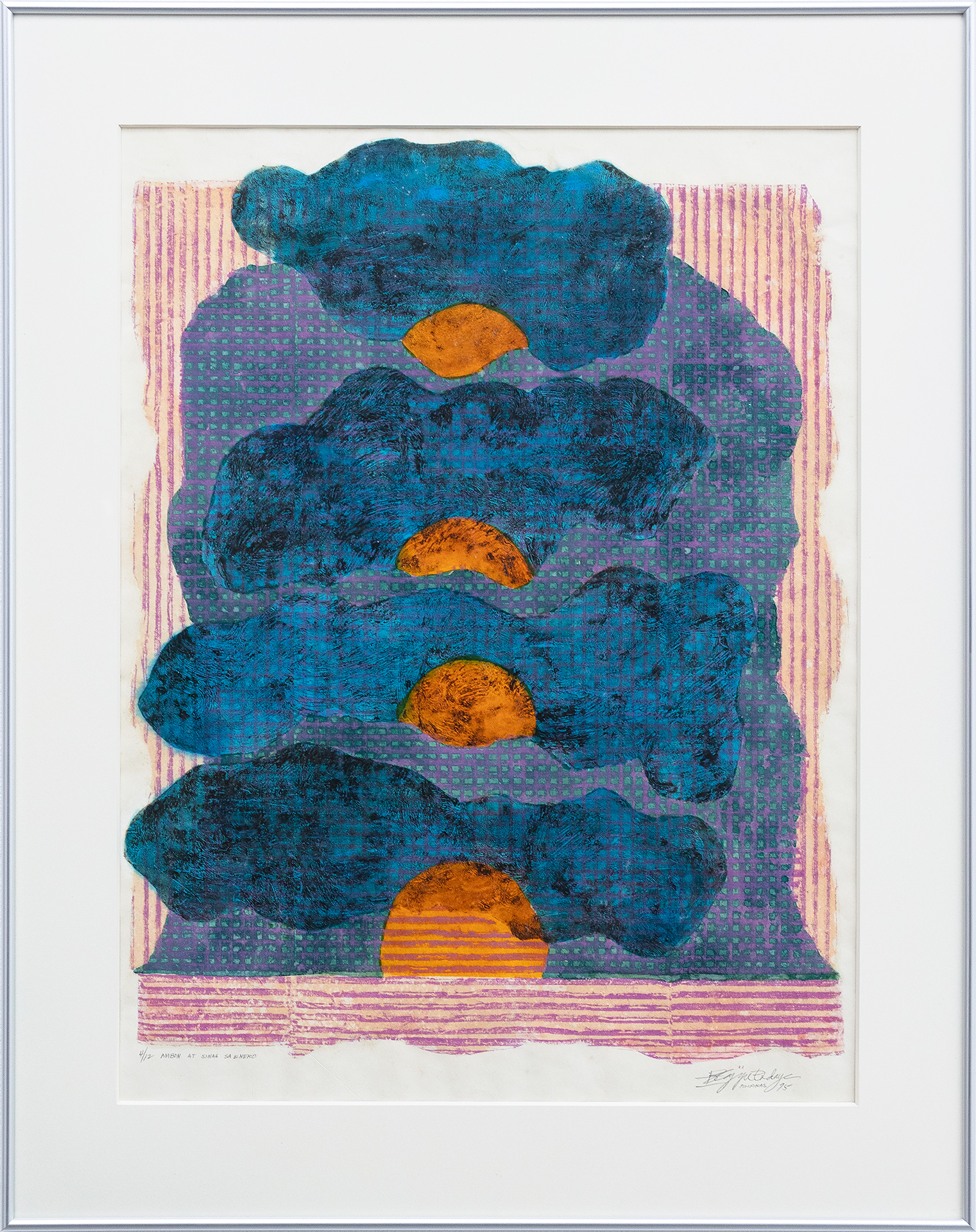

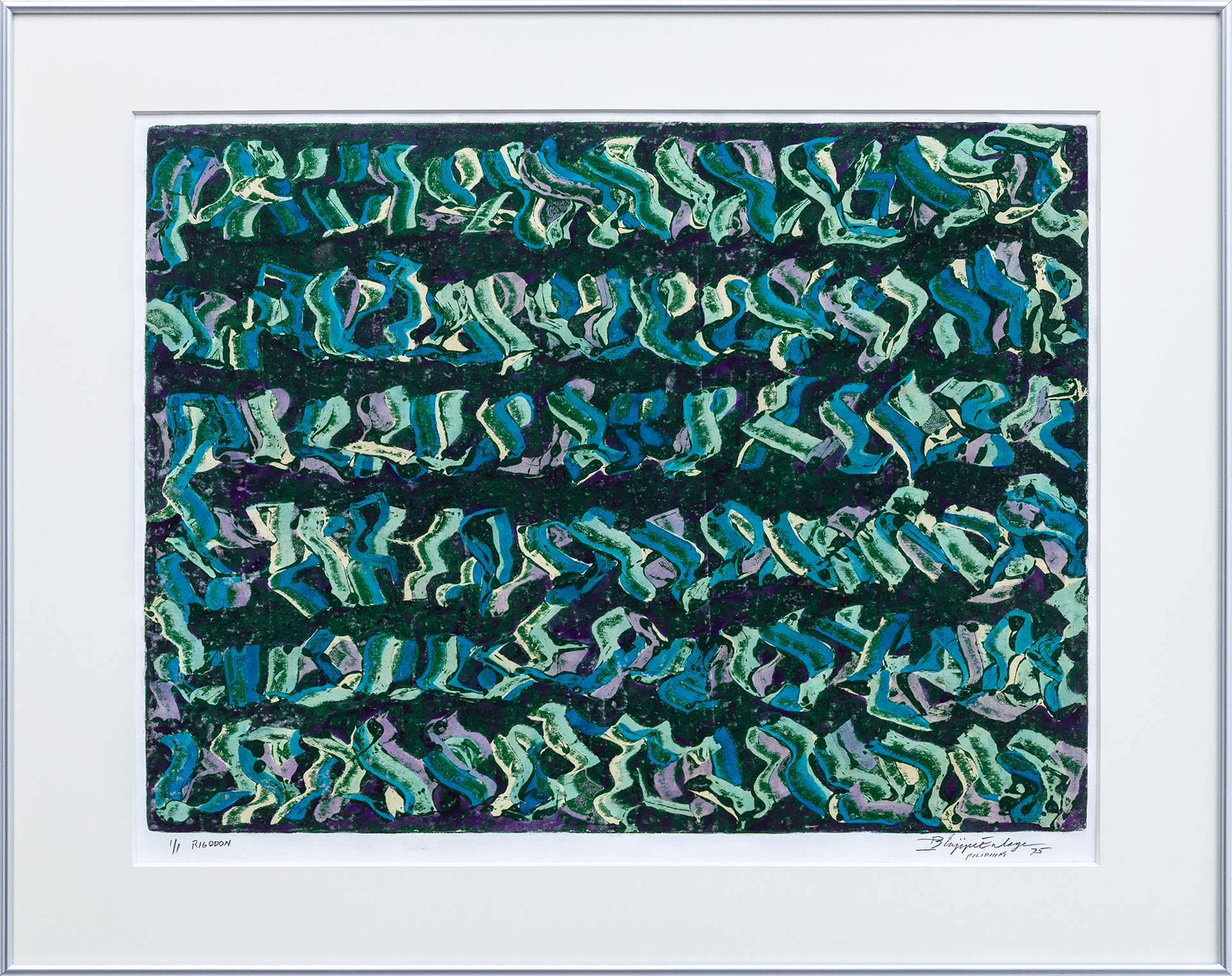

Rigodon, Imelda Cajipe Endaya’s inaugural exhibition at Silverlens, bursts with rhythm and vigor. In one work, four yolk-like suns align vertically behind dark clouds, as if in formation. There is order in these compositions—filled with grids and rows and repetitions. But its little details and movements feel free. Infinite loose, abstract lines move with grace across colorful planes, and tracing their paths feels like watching the improvised steps of a modern dance. Just as you begin to flow with its rhythm and beat, the dancer twists, turns, or leaps—and surprises.

Endaya is hailed for her large-scale, richly textured paintings and collages, as well as her strongly socio-political themes. Since the 1970s, her work has centered the plight of Filipino women throughout history: from the struggle for independence in the late 19th century, to present-day issues of migration and displacement. Yet, not many people know that in the mid 1970s—the early years of her career—she created vivid abstract prints. “Almost always I was burdened with guilt at doing abstracts,” Endaya declared in an artist talk in 1987. The 1986 EDSA Revolution was fresh in the nation’s memory, and she felt that as an artist, she carried the responsibility of visualizing the change she wanted to see in the world.

But today, when asked how she feels about these abstract works, she no longer carries guilt. They reveal a side of her that she wants the public to see—one that embraces play, experimentation, and joy.

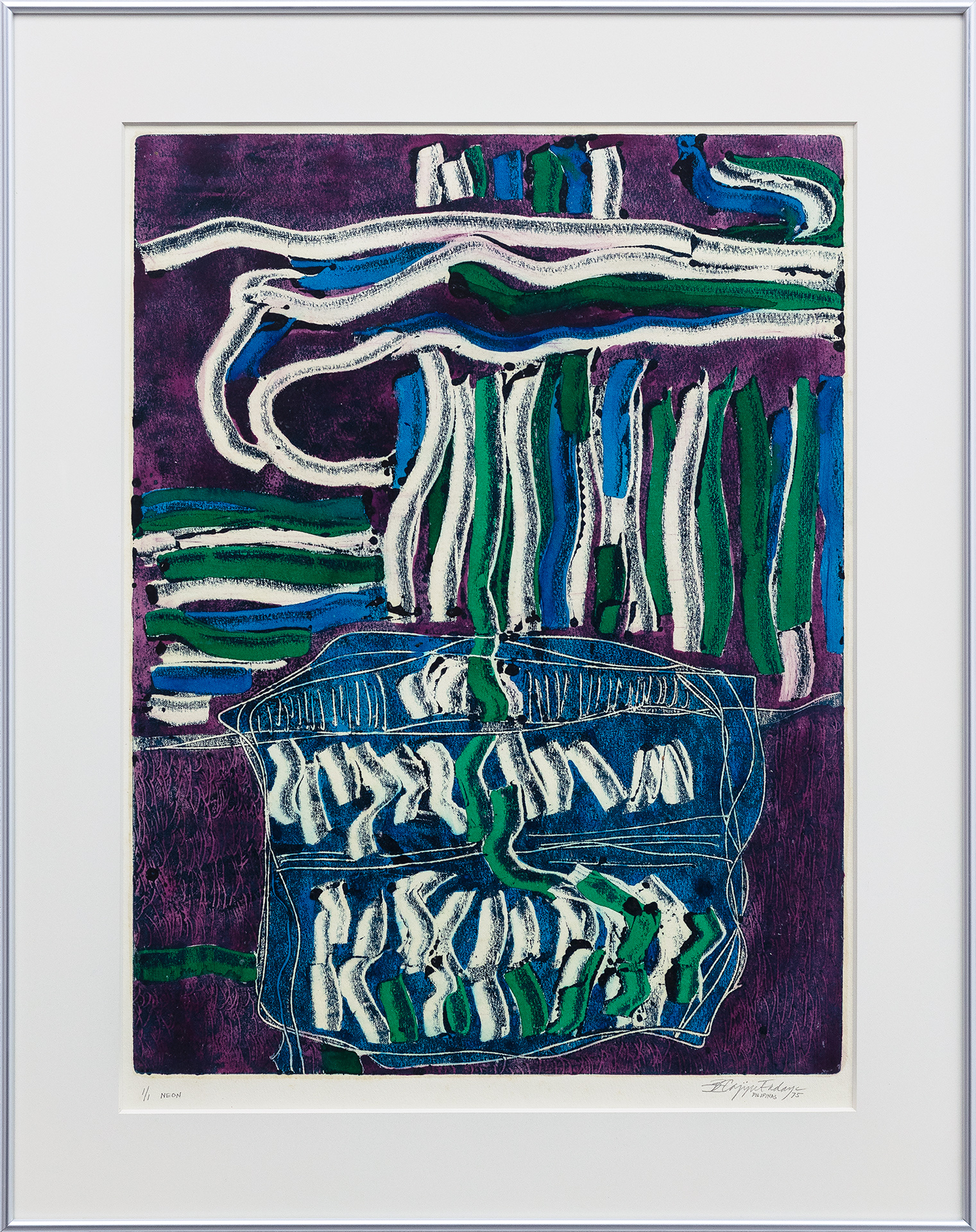

The eponymous piece Rigodon is named after a traditional court dance performed in the Philippines since the Spanish colonial era. Historically, the Rigodon was performed during grand occasions, such as state functions in Malacañang Palace, and paraded power and status. Performers typically don intricate Filipiniana; their movements are precise and elegant. Endaya’s Rigodon, however, seems to subtly break free from the dance’s rigidity. Performers are stripped of their ornate outfits and reduced to thick, energetic strokes in varying shades of green. The work seems to celebrate the dance’s communal spirit, rather than its allusions to hierarchy. It captures a story pervasive in Philippine history — in which Filipinos take the traditions imposed on us, imbue it with vibrancy, and make it our own.

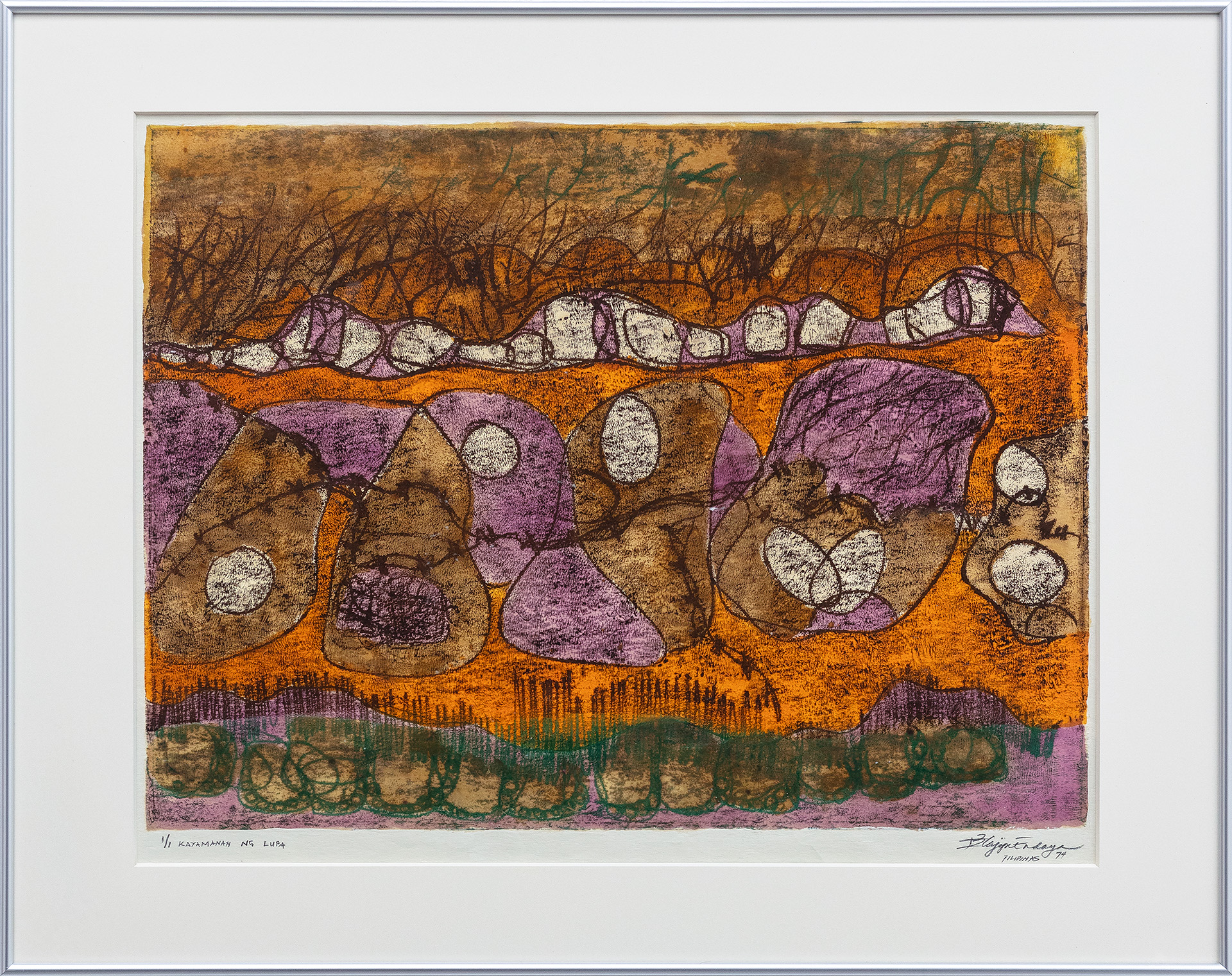

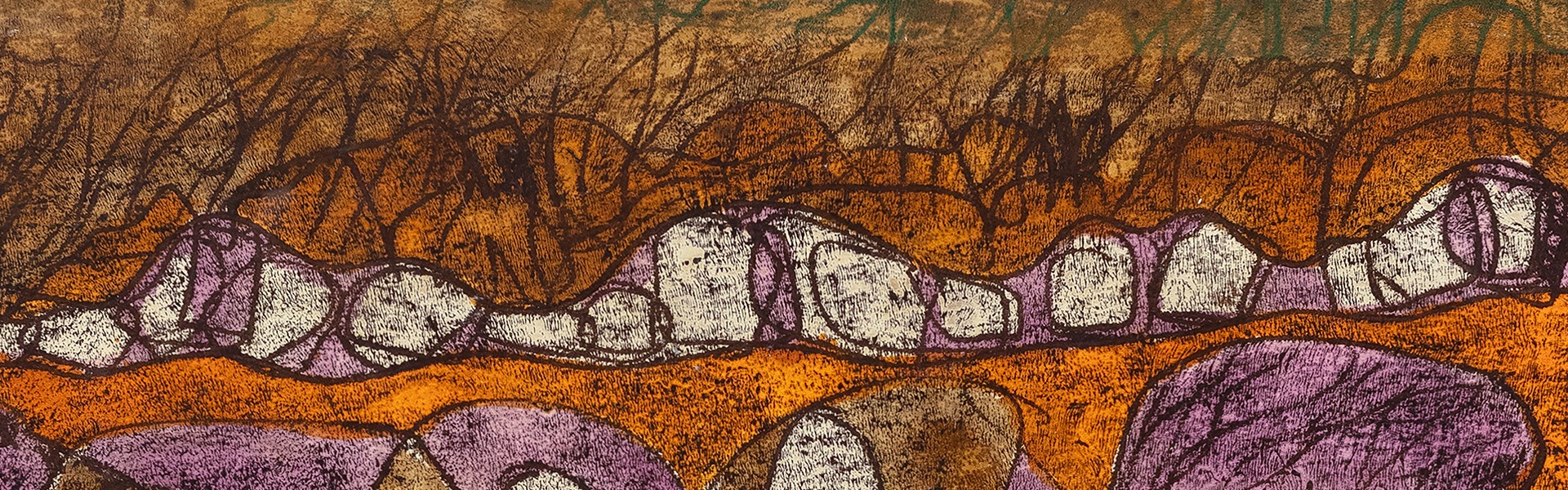

The works in Rigodon belong to the artist’s decades-long search for Filipino identity. Endaya created them as she worked on a separate series entitled Forefathers. In the mid-1970s, she grew enamored with images of our pre-colonial ancestors, and began featuring these figures in her prints. It is tempting to draw a neatly defined line between her abstract works and these more figurative, historical ones. But look closer, and you will see the line blur. In Forefathers, raw, gestural strokes surround images of pre-colonial figures; in her later series Mga Ninuno, these abstract strokes deface some figures, evoking the erasure of their native identity.

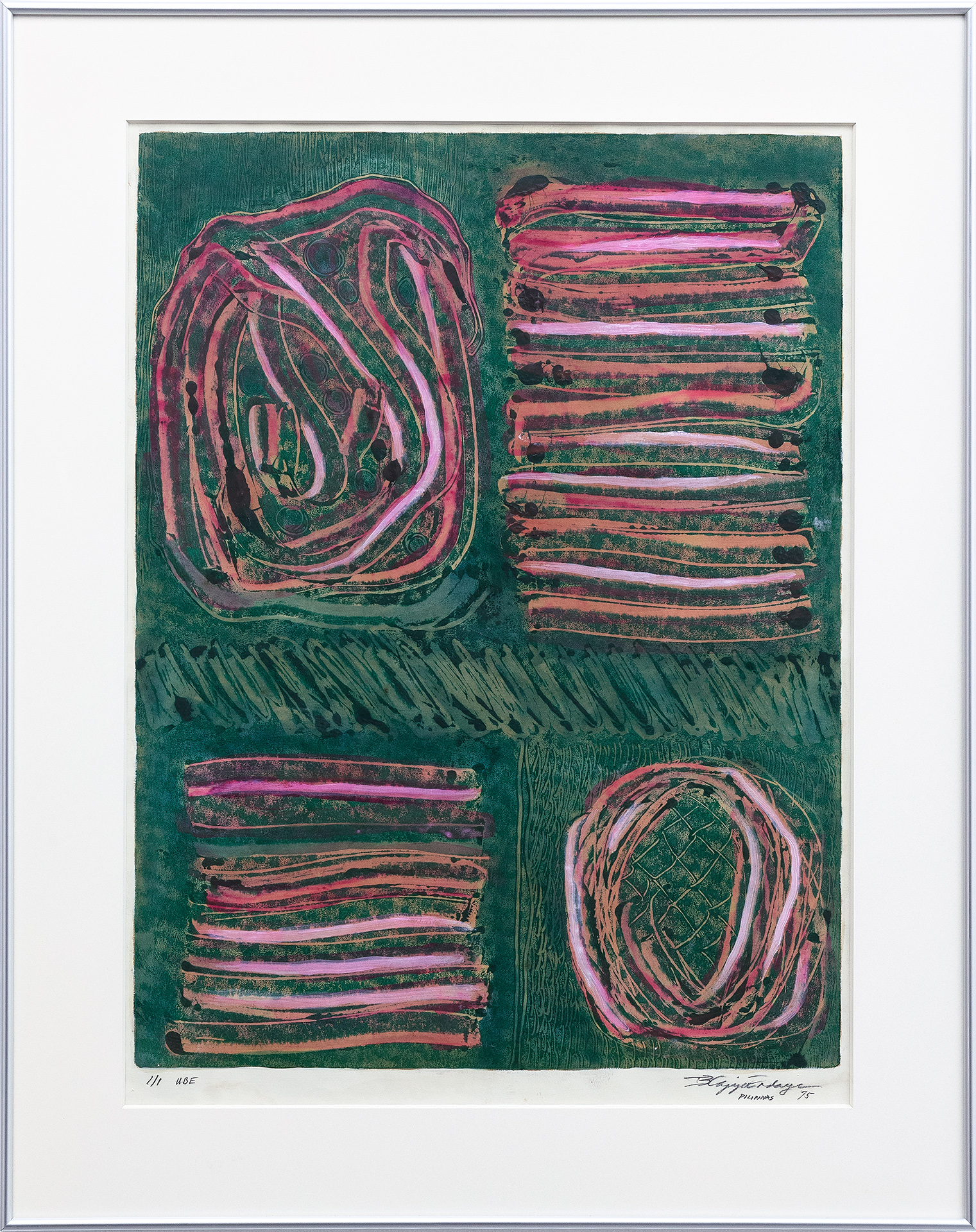

Even in her socially conscious figurative works, Endaya often starts her process through making abstract compositions—through play. This intuitive spirit underpins how she explores mediums, too. Most of her works in Rigodon employ dye-resist on oil transfer, a technique she began by accident. She explored etching at around the same time, and as she cleaned up her ink, she saw how much was leftover. Reluctant to let the paint go to waste, she began freely making abstract forms through oil transfer. There is a palpable energy in the lines, circles, and strange, amorphous shapes that emerged — as if they had long been contained, raring to be released.

This was the mid 1970s: Endaya had finished her Bachelor of Fine Arts at the University of the Philippines only a few years before. She was well-aware of the Philippine abstract artists who preceded her. Jose Joya and Constancio Bernardo had been her teachers. As a student, she created works that imitated the art of Juvenal Sanso and HR Ocampo. But in these abstract works from the 1970s, Endaya consciously resisted influence. Her artistic career was young and burgeoning, and she strove to assert her own voice. The results thus deviate from some Philippine modern artists who gained prominence after the Second World War—most of whom were men—whose works reflected traces of western influence, such as cubism and abstract expressionism. And, while unburdened by influence, Endaya’s abstract works bear closer affinity to the rhythmic repetitions of Nena Saguil, or the unabashed wit and colors of Pacita Abad.

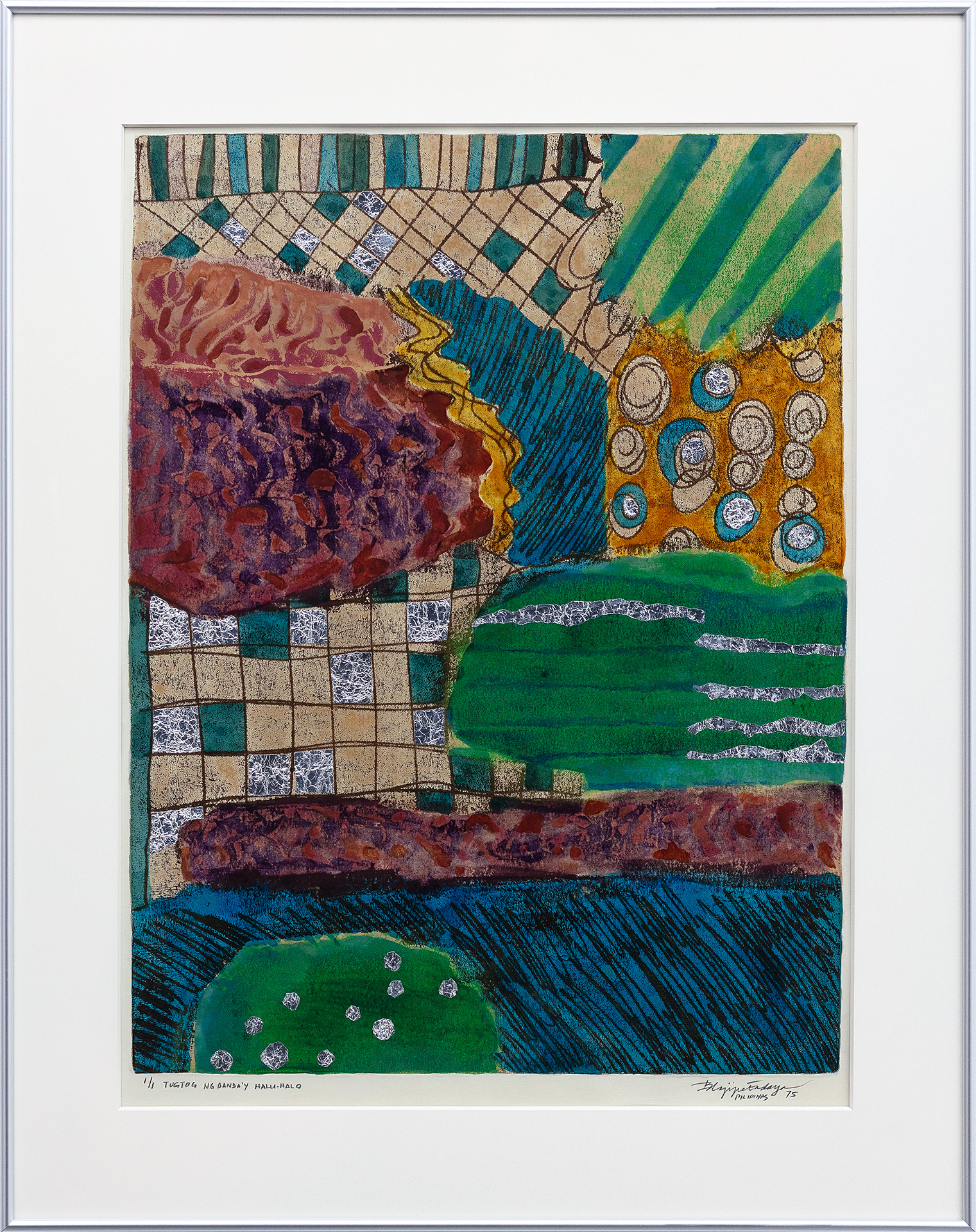

Rhythm and color pulsate in her work Ang Tugtog ng Banda’y Halu-Halo. Rhythm morphs throughout the piece—from steady grids; quick, restless lines; to loose and improvised squiggles. The colors are a rich mix of warm and cool, indeed like a classic halo-halo in the sweltering Philippine summer. Endaya shares that this work is her favorite in the show. It makes her feel happy, she says.

Endaya feels deeply—and this show reveals how her capacity to express joy is deepened by her empathy with the world around her. She believes that the joy she finds in art-making is part of what makes her human. One might argue that—in large part—it is this joy, alongside our historical struggles, that makes us, Filipinos, human too.

– Nicole Soriano

Imelda Cajipe Endaya’s (b. 1949, Manila, Philippines; lives and works in Manila, Philippines) artistic career has been devoted to contemporary social issues from the viewpoint of women empowerment. In her art, she has dealt with issues such as cultural identity, human rights, migration, family, reproductive health, globalization, children’s rights, environment, and peace. Her mixed media paintings and installations are richly colored and textured with crochet, laces, textiles, window, flatiron, suitcases, papier mache craft, and found objects from home and popular culture. In so doing she developed a visual language that is distinctly womanly and Filipino.

Endaya is also a writer, curator, and art projects organizer. She co-founded KASIBULAN, a collective of women artists, and Pananaw: Philippine Journal of Visual Arts, an initiative in contemporary art discourse. She was affiliated with the Philippine Association of Printmakers from 1970 to 1976 and the National Commission for Culture and the Arts Committee on Visual Arts from 1995 to 2001.

Endaya’s works are in the collection of Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, Cultural Center of the Philippines, Philippine National Art Gallery, National Gallery of Singapore, Metropolitan Museum Manila, Okinawa Prefectural Museum, and Fukuoka Asian Art Museum. Among her awards are Ani ng Dangal from the National Commission for Culture and the Arts in 2009, Republic of the Philippines CCP Centennial Honors in 1999, Araw ng Maynila Award in 1998, and the CCP Thirteen Artists Award in 1991. An art educator in the non-formal set-up, she conducts lectures and art workshops.

Works