Library Bookworks

Renato Orara

Silverlens, Manila

Installation Views

About

THE RAPTURE OF RUPTURED TEXT:

RENATO ORARA’S “LIBRARY BOOKWORKS”

by Carina Evangelista

There is something precious about books. You hold a book in your hands. You flip its pages. You curl up with it and shut the world out as you enter the world of words and meanings it offers. When it's really good, it consumes you as you consume it.

There is something powerful about books. They're just bound sheets of paper and yet they bear so much meaning they're either sacred or banned. It was a pleasure to burn. That’s the first sentence and a paragraph unto itself in Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, a blistering portrait of a society suffocated by conformity, where knowledge such as that found in books is contraband that gets smoked out then torched.

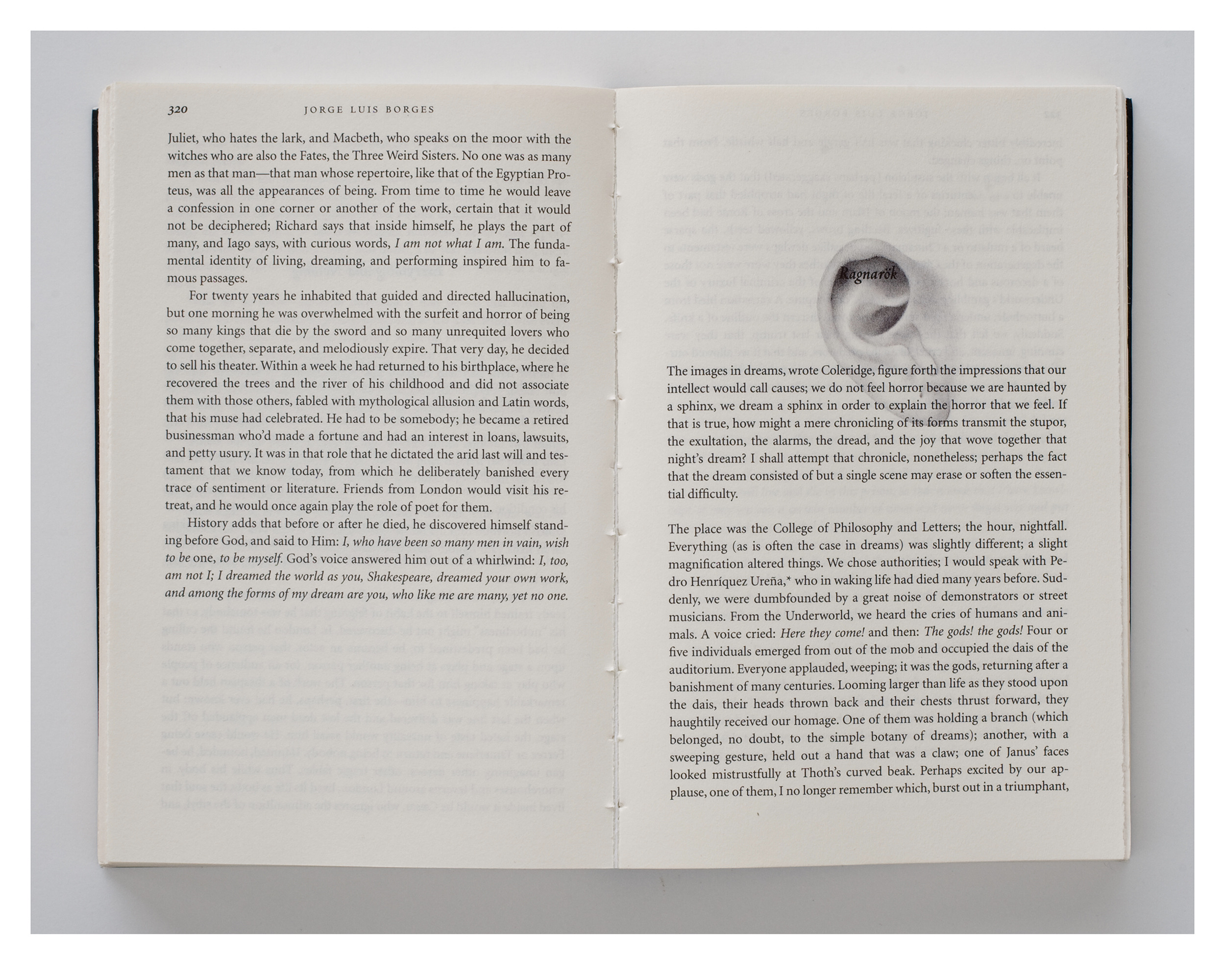

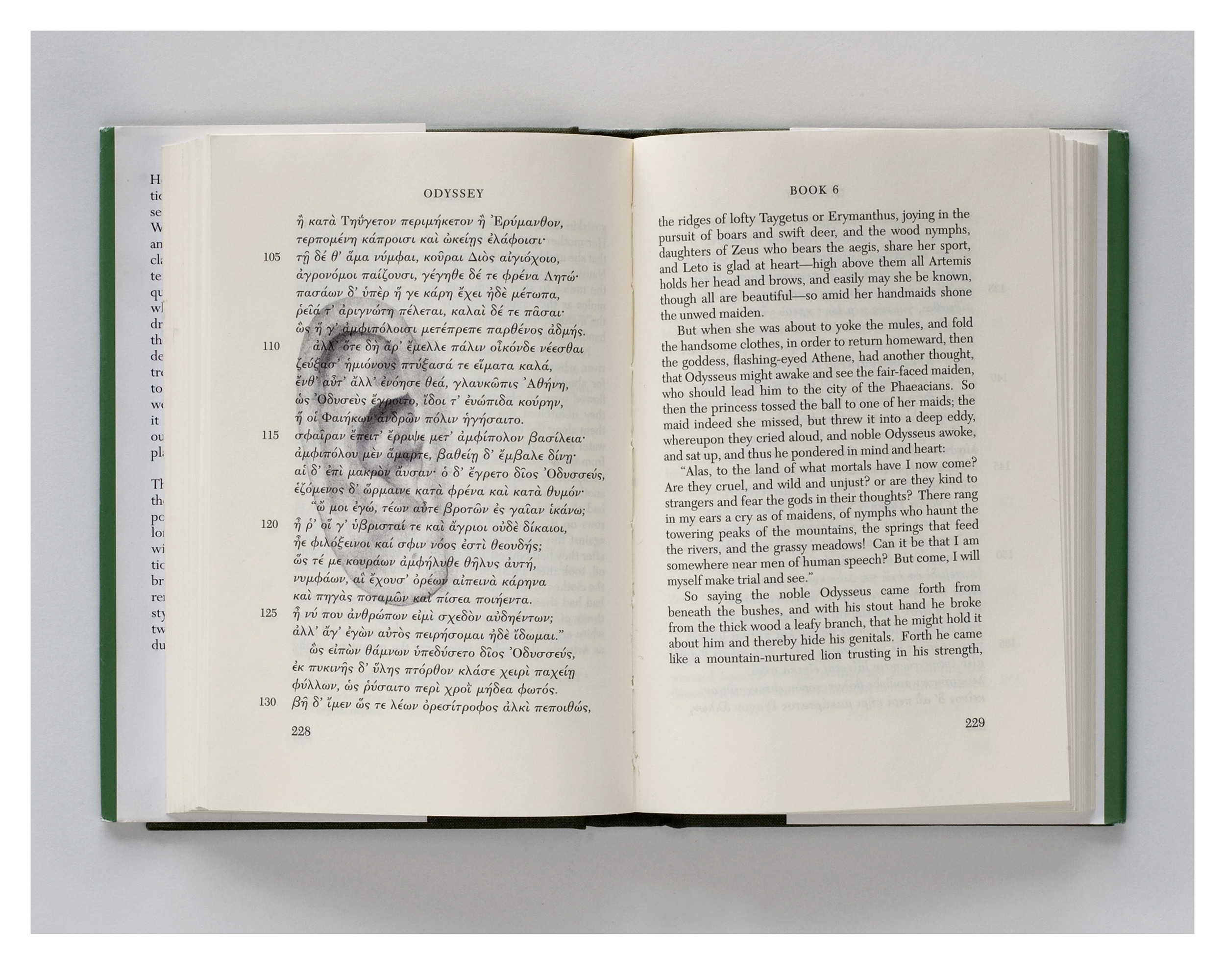

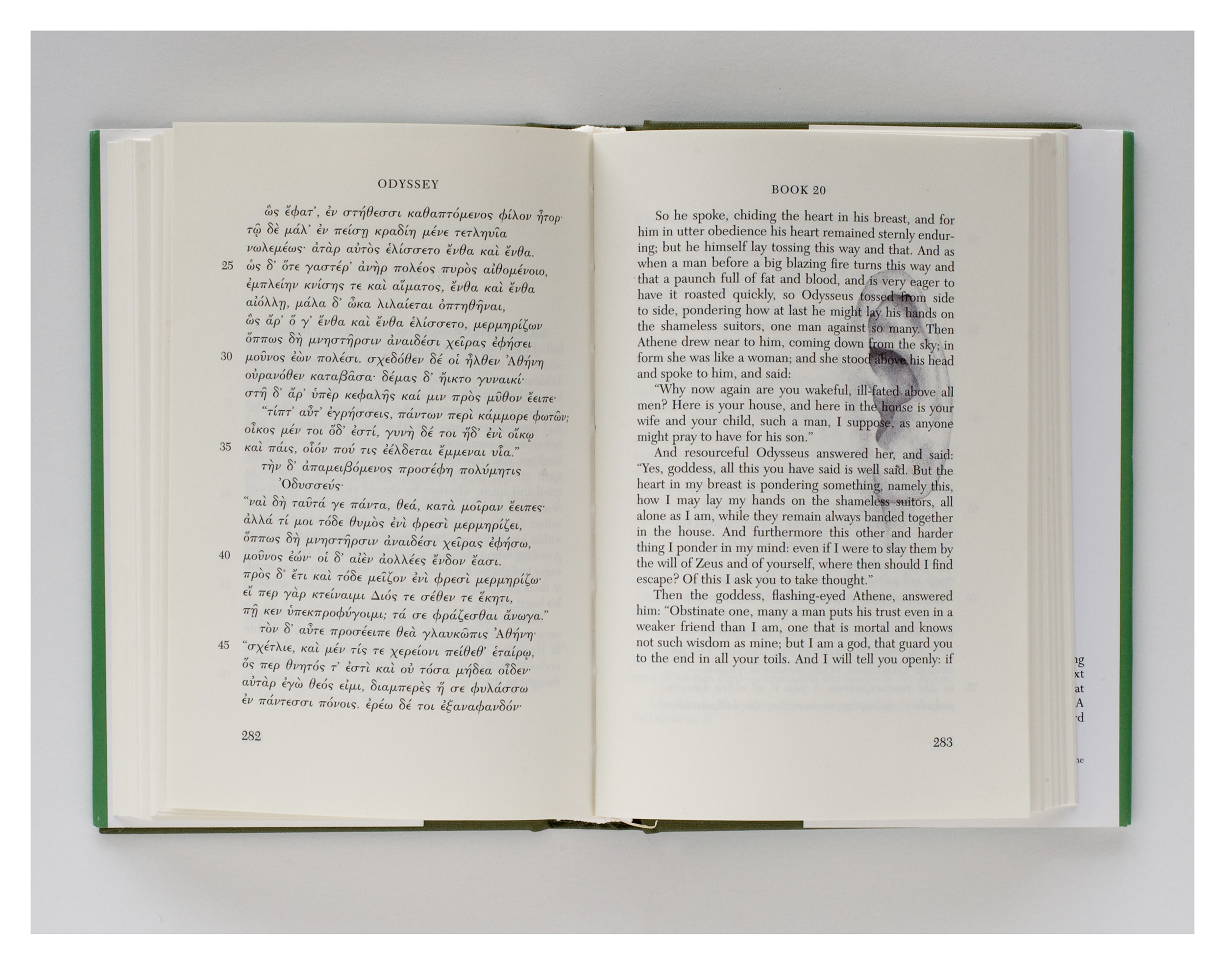

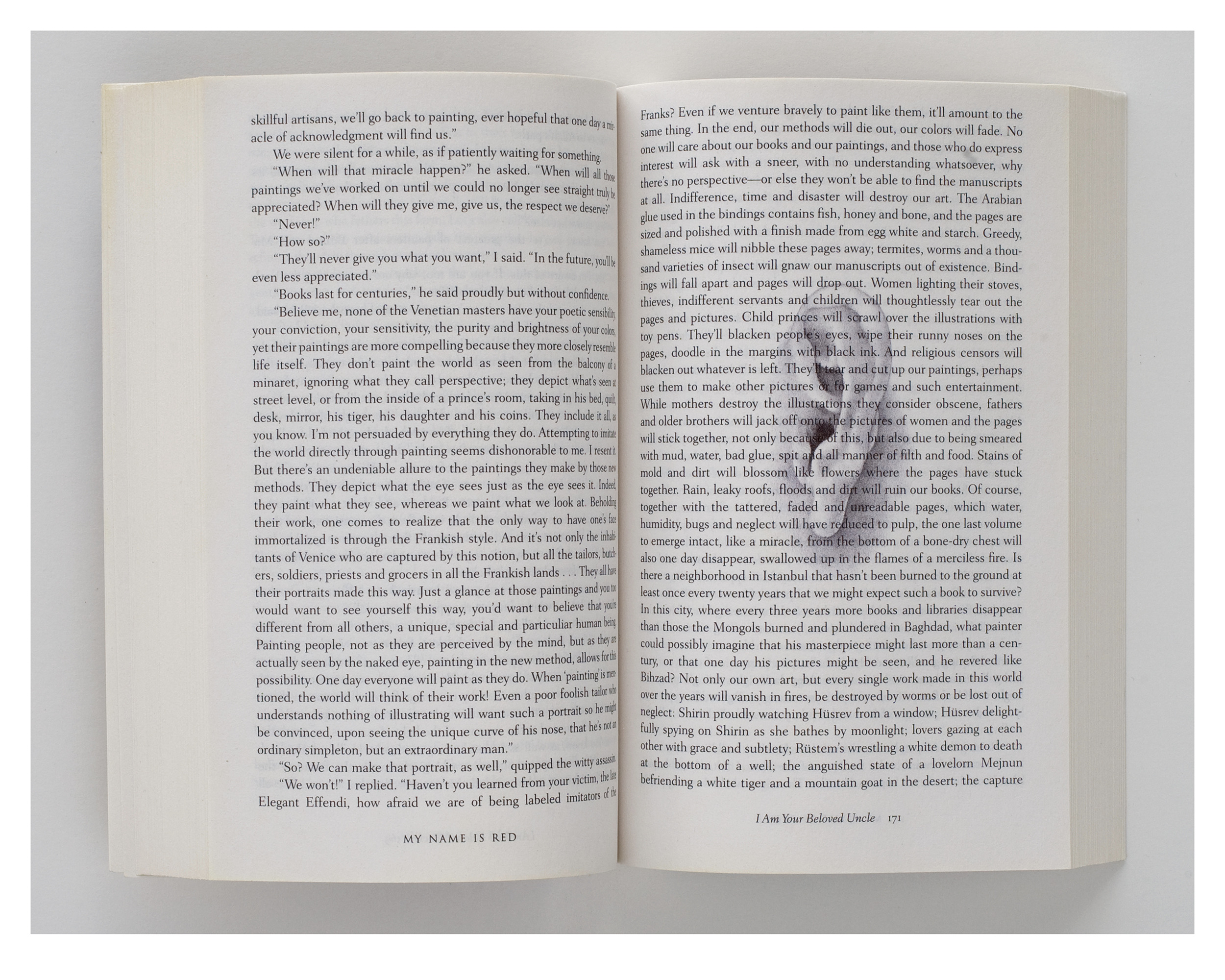

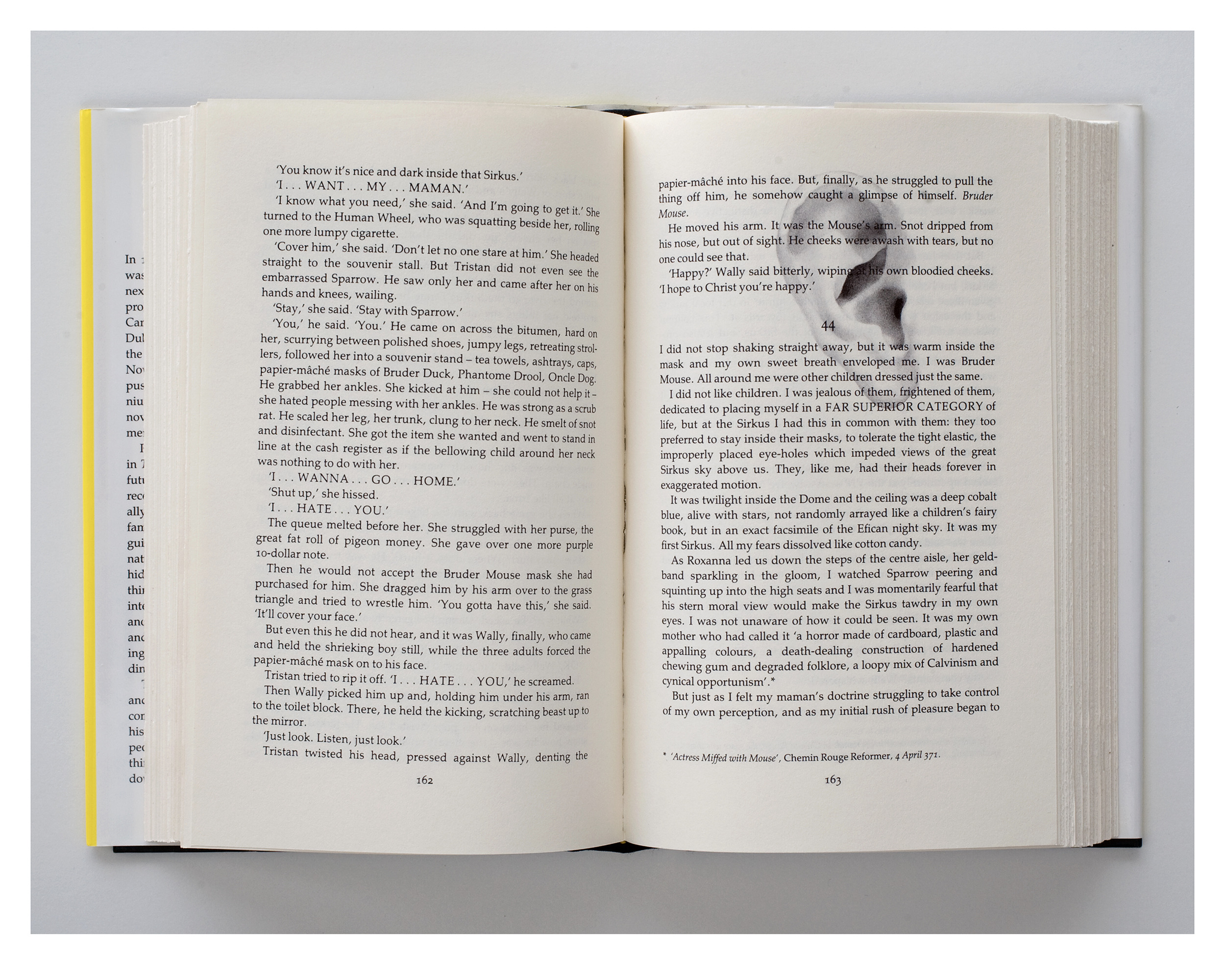

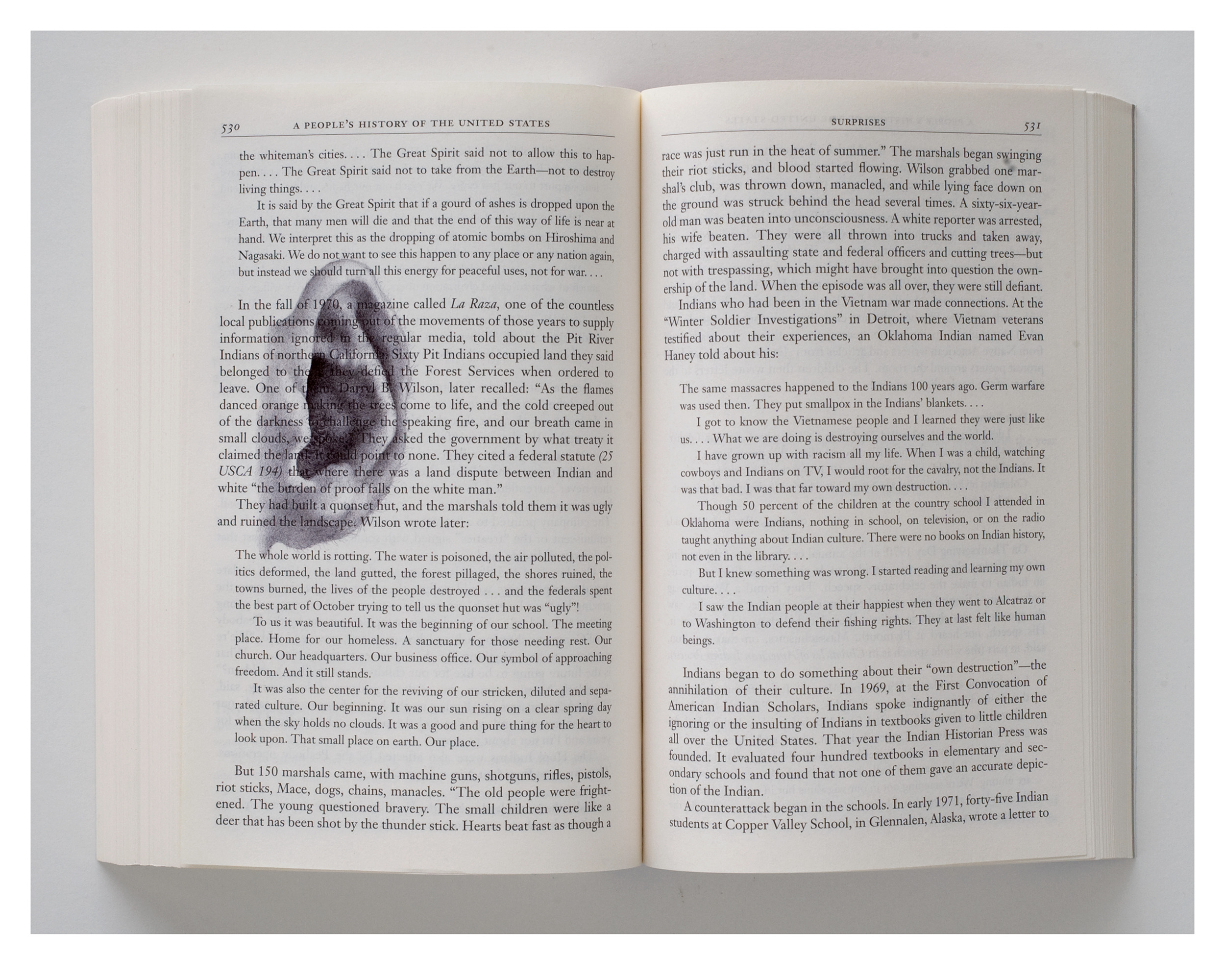

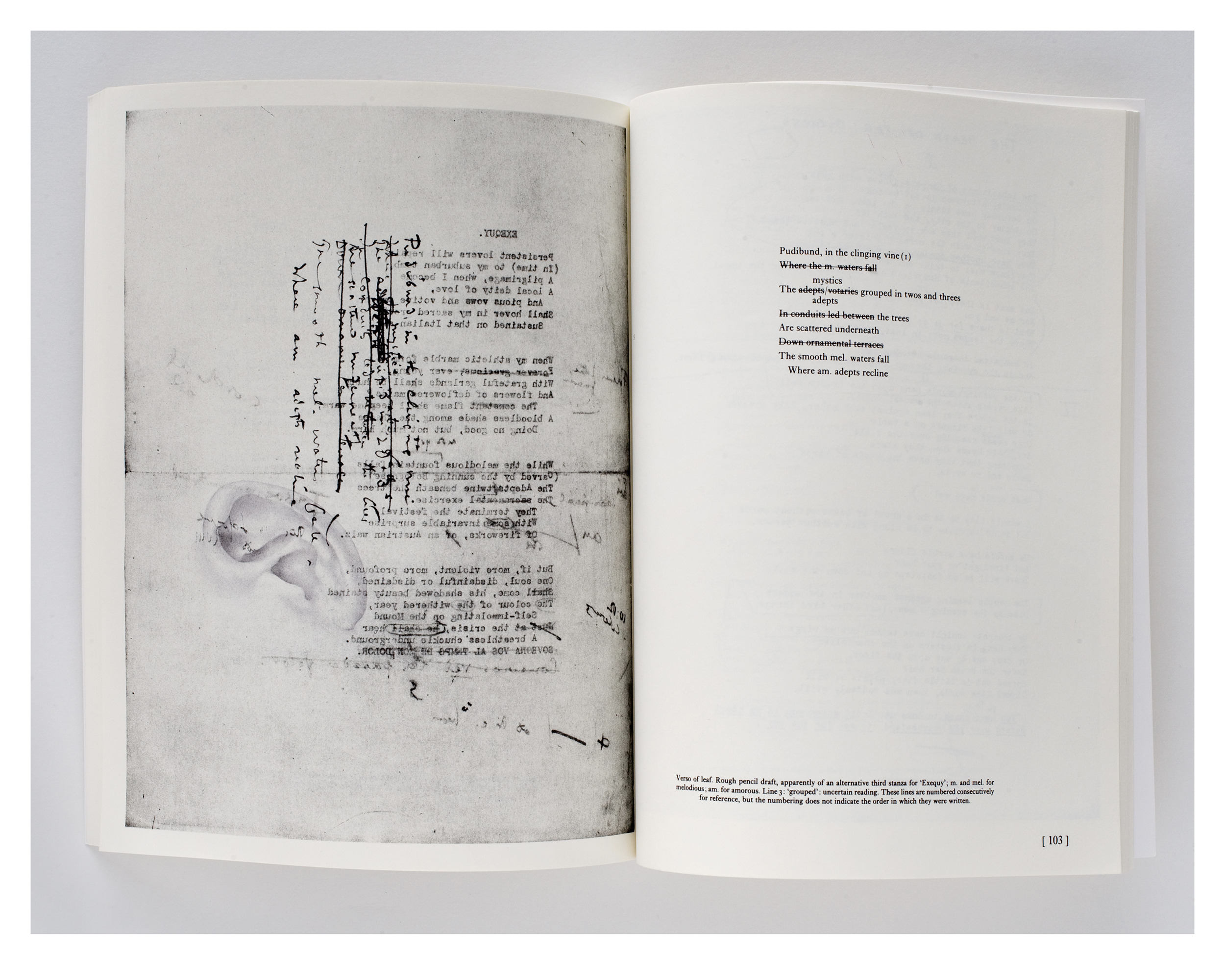

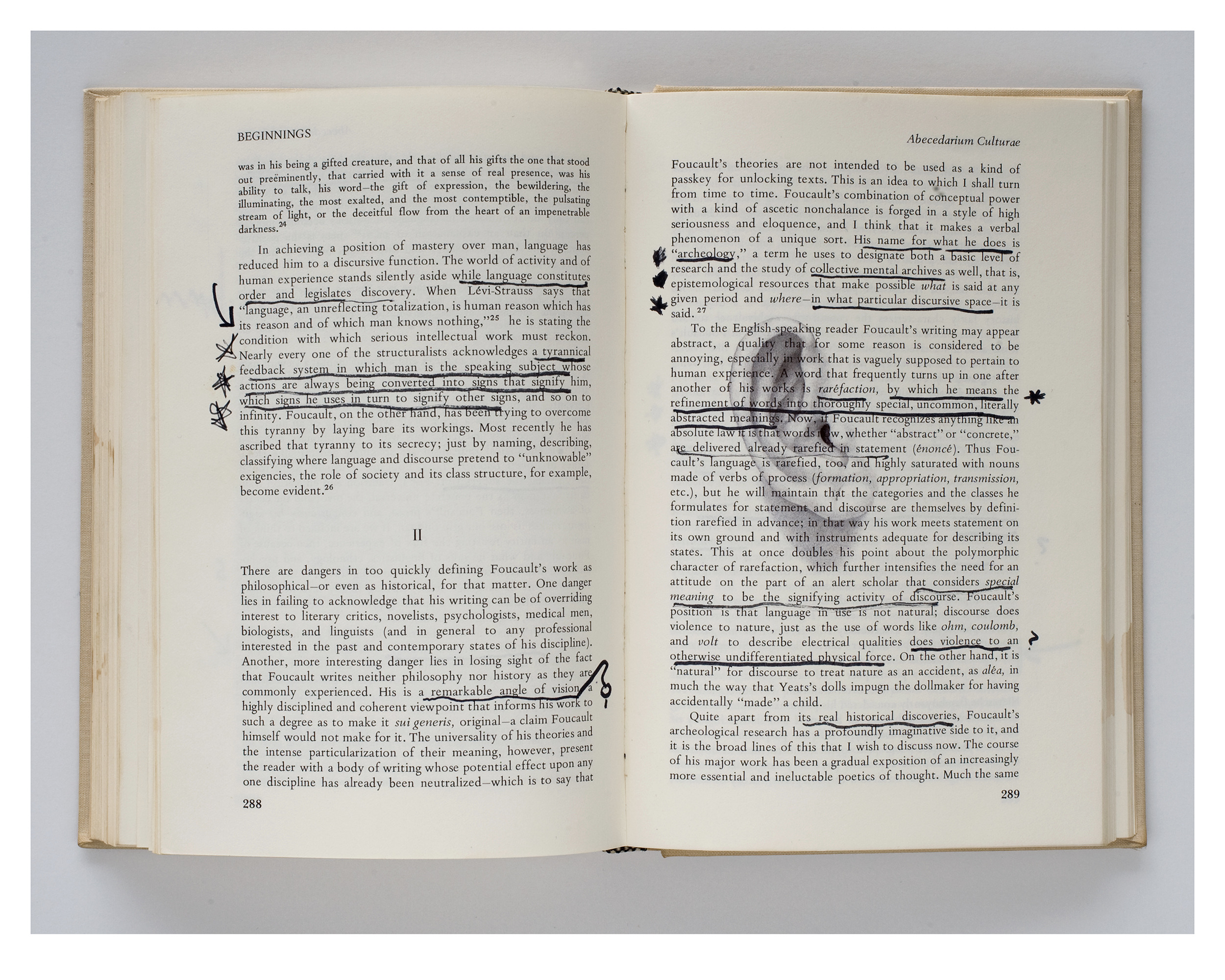

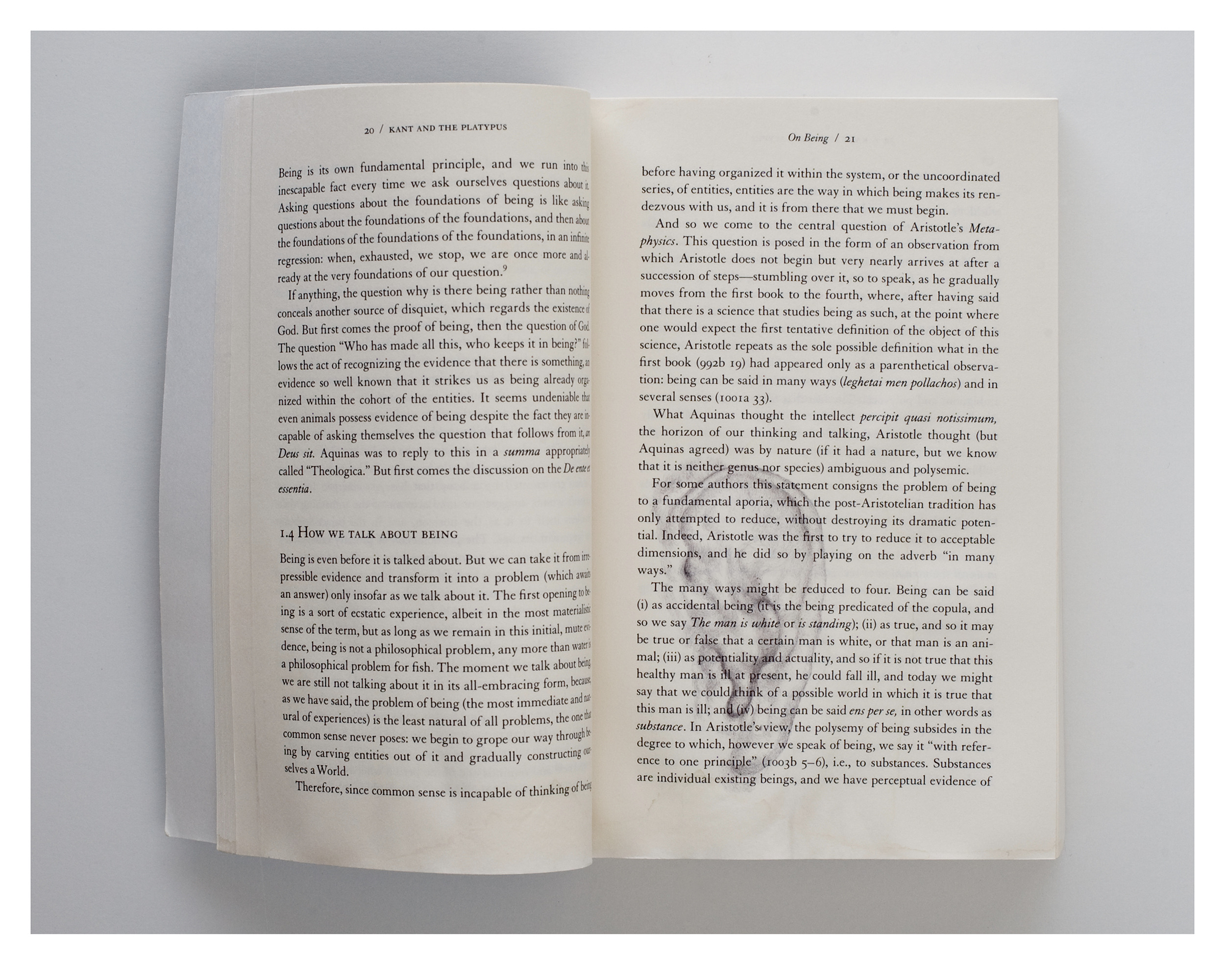

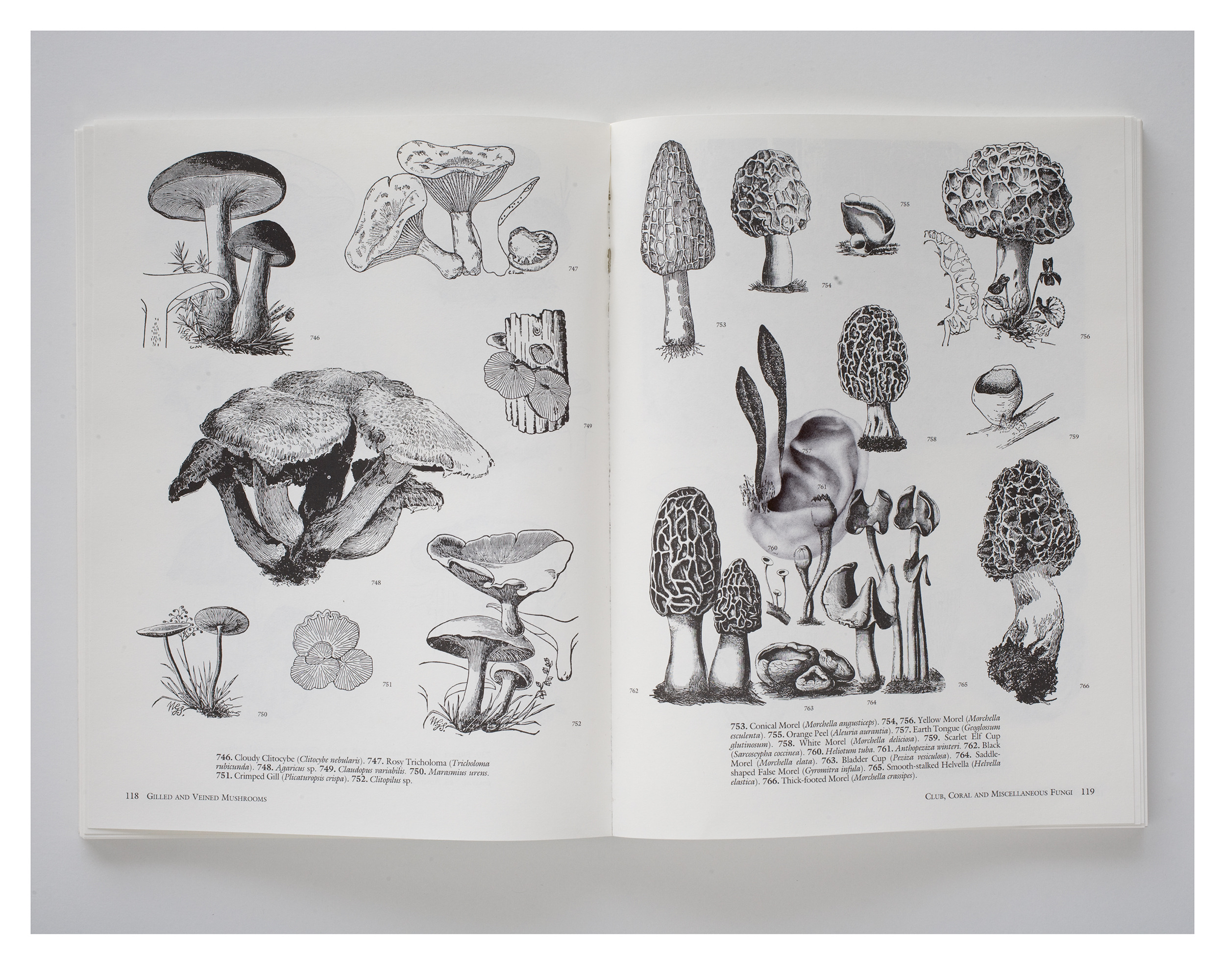

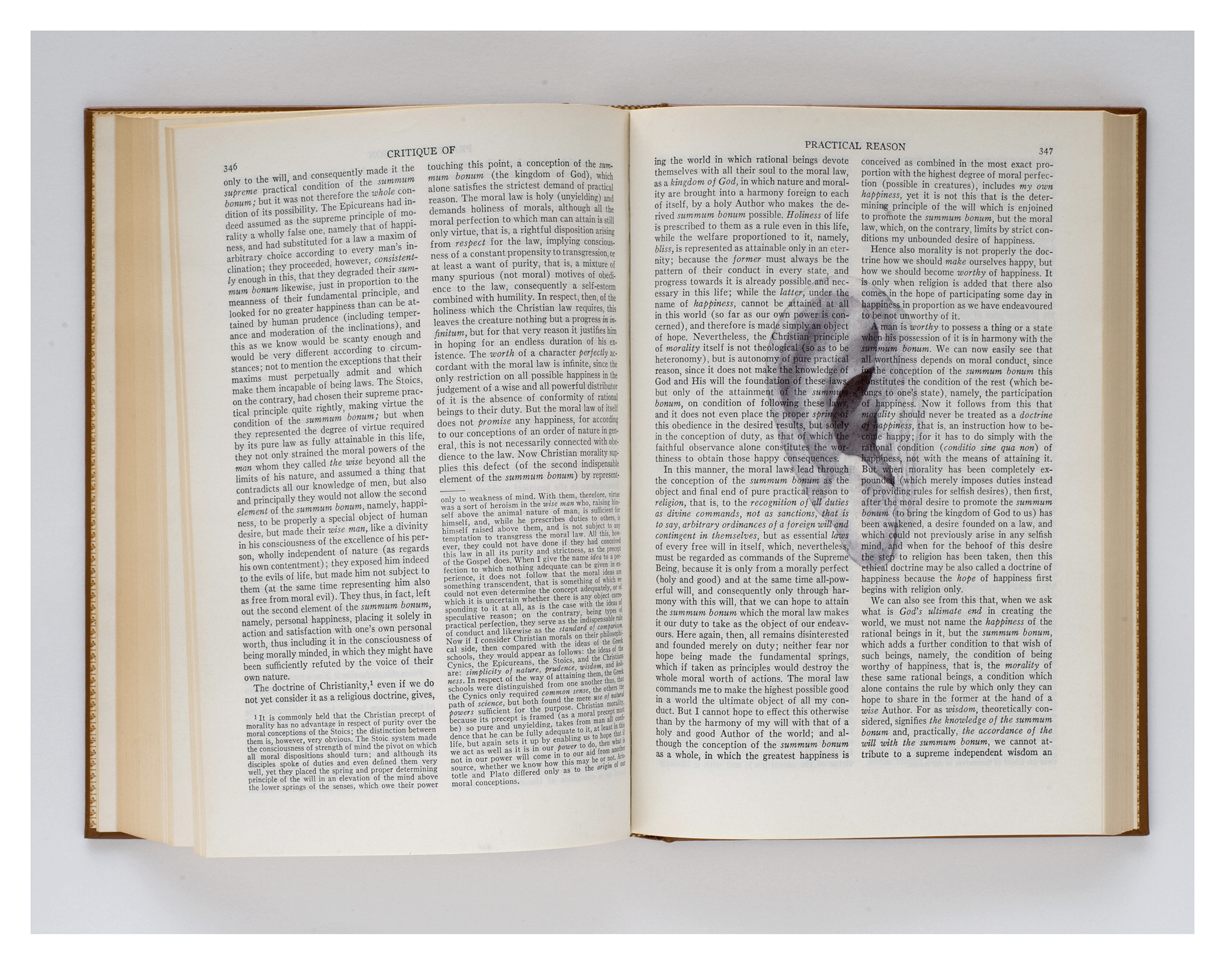

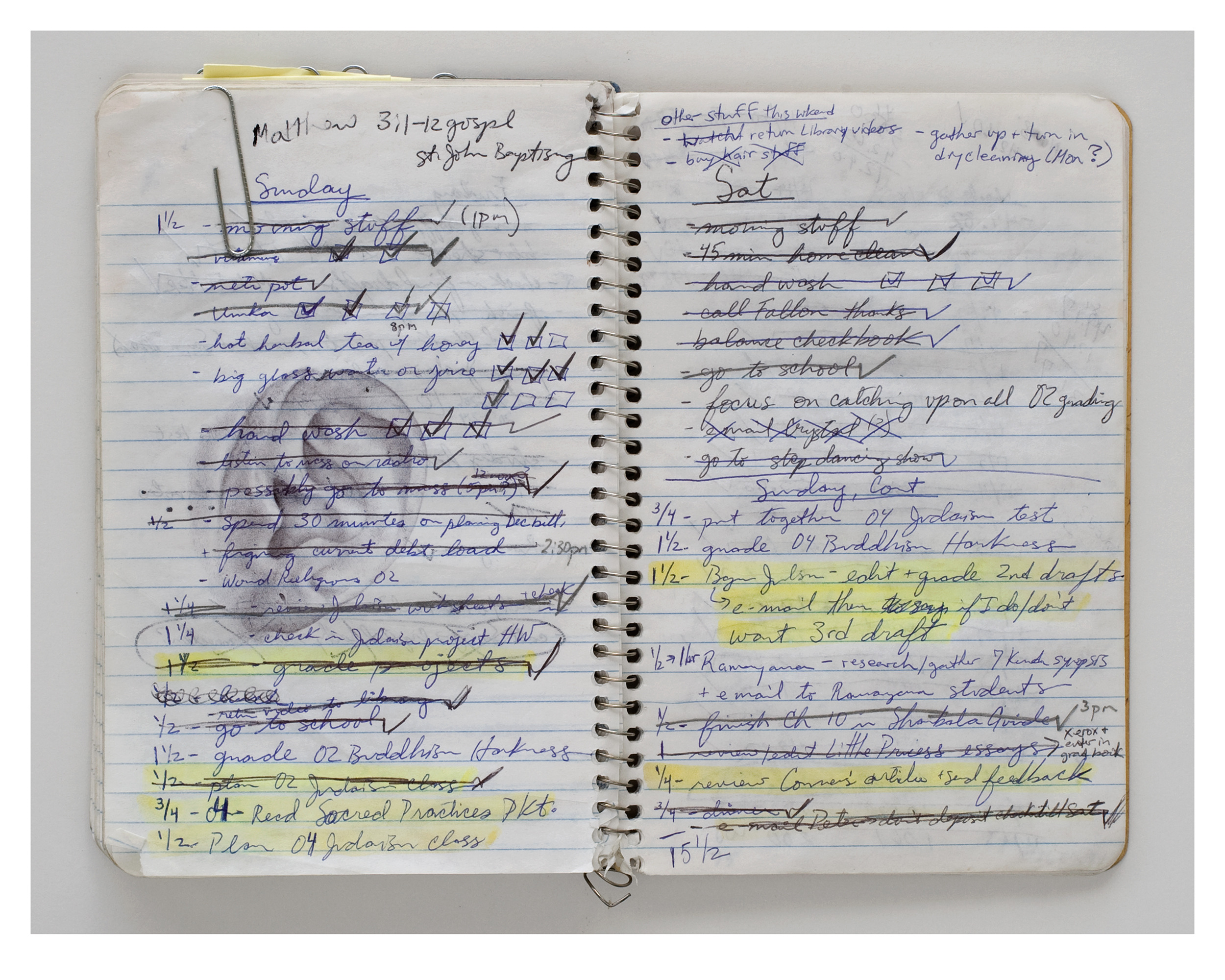

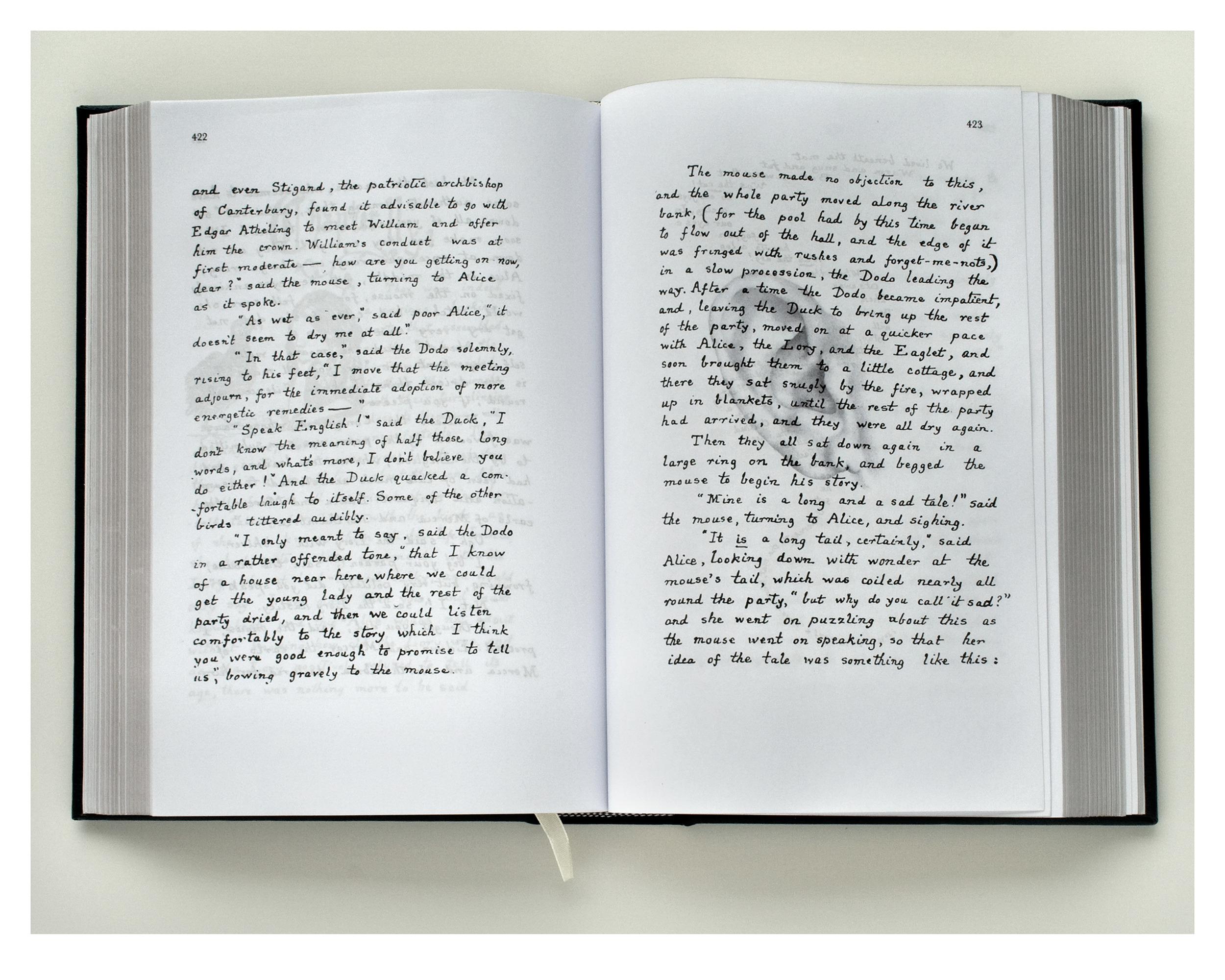

Renato Orara's Library Bookworks are interventions on these precious, powerful objects. He chooses a book and selects a page and decides on the portion of the selected page on which to draw a particular ear. Each ear drawn is a representation of the ear of someone in his personal circle of family and friends. The books range from the classics to contemporary fiction and non-fiction to a notebook filled with lists and scribbled thoughts to a book of botanical illustrations to a pop-up adaptation of Alice in Wonderland to a volume of accounts of radical voices in US history to a facsimile edition of TS Eliot's The Wasteland that features Ezra Pound's annotations.

This series exemplifies Orara's skill at achieving permutational variability within a simple formula, in this case a book on which to draw an ear with a ballpoint pen. Orara has dedicated decades of his artistic life to the discipline of drawing, of making marks on paper, of building on layers of opacity and transparency, of shaping the chiaro with the oscuro, of distilling the essence of the drawn object into an image so concentrated that it becomes—simply becomes. Of the first incarnations of these drawings, he wrote: "Ten Thousand Things that Breathe is simple, yet extreme. Objects are stripped of their context, rendered in infinite layers of ballpoint ink—their essential energy magnified on paper—until the viewer is left just looking, just breathing, just being. I draw to stop the mind."

But his is not an artistic ethos that is constricted by the meditative rigors of drawing alone. Corollary projects spawned by Ten Thousand Things that Breathe involve both an engaged and engaging conceptualism. With playful intimacy, he rifles through other people's drawers for objects to draw so that the selected object and the corresponding drawings sit side-by-side in the drawers upon return to their owners. The so-called pipe sitting next to the drawing of the pipe is Orara winking at René Magritte and Ludwig Wittgenstein in the cozy jumble of things secreted away in a drawer.

With gravitas, he handwrites hundreds of names of Iraqis killed since 2004 in upside-down, mirror script that humbly echoes the arabesques in Arabic writing. He then carefully draws simple objects—the evidences of life and living—over the lines of the names of the dead. A bunch of watercress, a pair of socks, fruit, strewn caperberries, a cup and saucer with coffee “silt” staining the inside of the cup, a balloon still buoyant with air. These seem to be simple markers of lives suddenly whisked away by war from the elegant clutter and ordinariness of daily life. Avoiding blatant political pronouncements, the artist simply memorializes the dead by quietly and carefully “uttering” their names on paper.

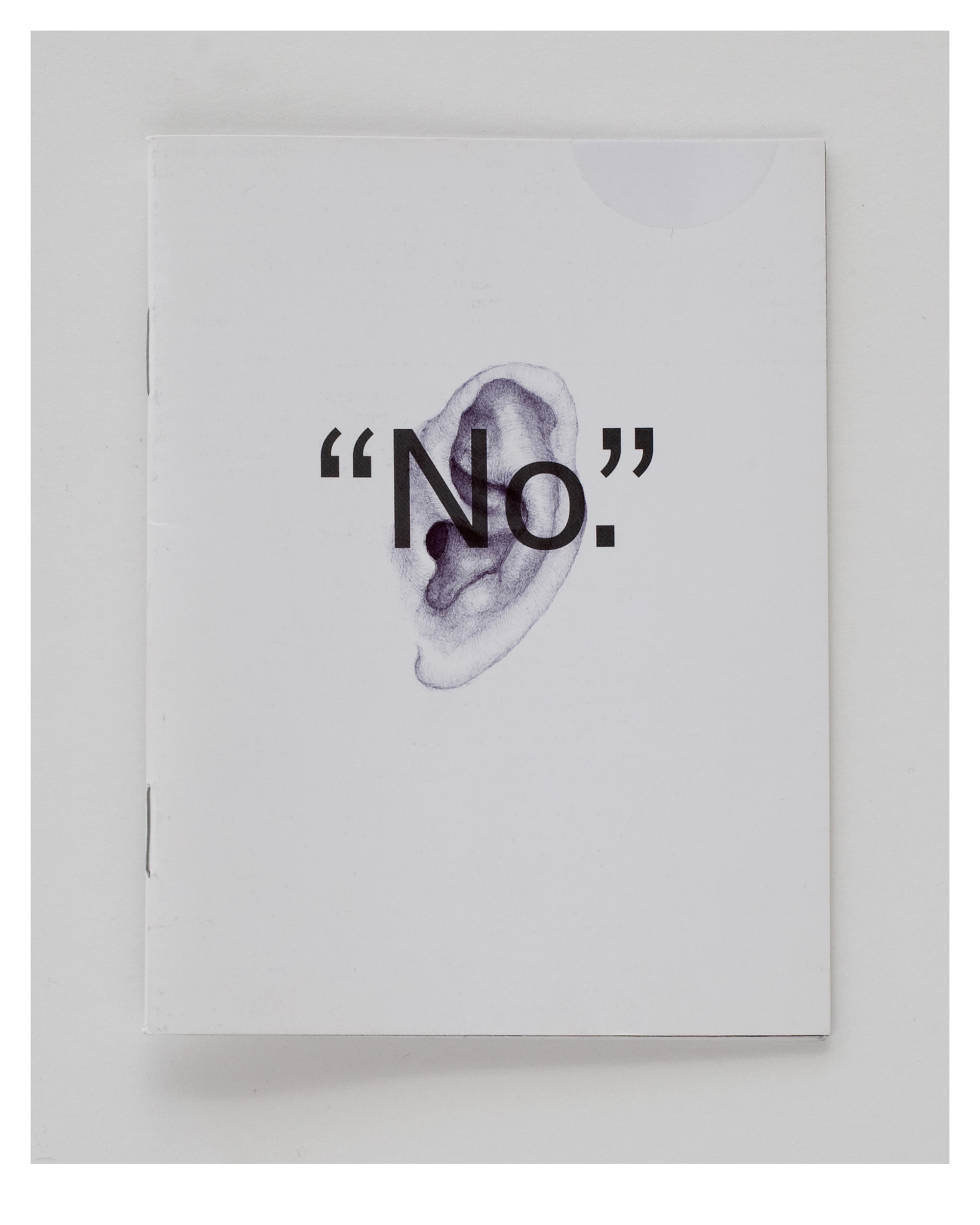

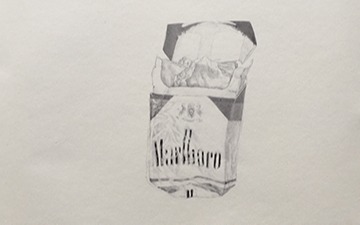

And with linguistic mischief in Bookworks, he translates his love of literature and philosophy into simple semiotic somersaults. Declaring his full intent "to disregard the meanings embodied in the book's content," he has superimposed drawings of cuts of meat over biblical passages, anatomical parts and nudes over dictionary entries, and human ears over library book texts.

In the Library Bookworks series produced for his one-person show in the Philippines, Orara intervenes both with the books and various library systems from Baguio to Manila to Zamboanga and Dumaguete. The books, each opened to the page which he has altered with a drawn ear, were photographed and given titles according to the respective call numbers assigned by participating libraries who have agreed to acquire the books for their collections.

The photographs on view at Silverlens Gallery function as map markers to the originals neatly tucked away in the shelves of their new homes. According to the artist, this cross-referencing allows him to turn the gallery into a library and the library into a gallery. Altogether, the network of photographs and drawn images urges viewers not just to consider the work but also to go on a kind of pilgrimage from ear to ear, book to book, library to library. This manner of intervention and insertion is the artist's attempt to place art in public spaces without the heft and pomp of a public sculpture but with the intimacy of a photograph in a locket. The artist, the gallerists, and the participating librarians know where they are. Those who learn about this particular series and care to find these drawings could locate them. And for the unwitting library visitor who might chance upon that inserted ear, a surprise and a mystery.

Books are compilations of words and meanings, thoughts and ideas. Ears are collectors of sounds and transmitters of data to the analytic mind. Ears are also erogenous zones. Inserting them visually in random pages is an interruption of the flow of information. At first sight, one is taken aback by its unexpectedness. Upon deeper consideration, the ear seems to remind the reader of the prosodic nature of prose: the rhythms, the pauses, the intonations that cumulatively shape meaning out of sound. In Edward Said's Beginnings, Orara refers to the drawn ear as a third presence. There is a polyphony of presences in it: the author's voice, a reader's interpretative emphases betrayed by the marks made by a previous owner of the book, and the artist's drawn ear.

By superimposing ears over lines of printed words—here straddling the clean white space between the classic two-column blocks of text, there simulating a visual cocoon over a title, in another ear with its dimpling almost a visual pun on the water-damaged paper on which it is drawn, and in yet another so lightly drawn as to seem more like a pentimento than an overlaid image—Orara arrests the flow of these thoughts and ideas at least for a moment on a page. He calls the reader's attention to both the visuality and the phonology of words, their very materiality and very being beyond the thoughts they are conscripted to service, the imagination they are anticipated to stoke, the interpretation they are commandeered to accommodate, and the weight of the philosophical, literary, or political import they are expected to bear. His attempted cancellation or suspension of meaning through the encroachment of a non-sequitur image upon printed matter is his way of creating a pocket of "vacuum" within the density of text—one which he nonetheless accedes is inevitably vulnerable to being open to different kinds of interpretation and different conflations of meanings because "nature abhors a vacuum."

Seek out one of these books or stumble upon it. Encountering the drawn ear is like chancing upon an illuminated manuscript, except that it seems to be the kind of grotesque (term used for the thumbnail sketches found in the margins of illuminated manuscripts) that Samuel Beckett might allow to adorn his writing. To Beckett, "There is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, no desire to express, together with the obligation to express." As with the bizarre beauty that is in Beckett's ascetic expressionism, there it is in the categorical simplicity of a drawn ear over a single word that is a sentence unto itself: "No." It is a pleasure to behold.

Library Bookworks by Renato Orara runs from January 8 to February 14, 2009 at SLab (Silverlens Lab). There will be an opening reception on January 8, Thursday at 6pm. Renato Orara will also have a live online artist talk on Janaury 17, Saturday at 12nn. Library Bookworks will be shown along with Family Spaces by Stella Kalaw at Silverlens Gallery.

Carina Evangelista is Curator at the Delaware Center for the Contemporary Arts. She has enjoyed, suffered, and survived but never regretted any of the many verbal sparrings she has had with the artist Renato Orara since they first met at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1996 where she worked on numerous exhibitions and publications.

My work is a meditation on the nature of presence, of being. I find an object and draw it until it breathes.

A series of drawings of objects rendered on uniform blank sheets of paper, Ten Thousand Things that Breathe forms the core of my work. Ten Thousand Things that Breathe is simple, yet extreme. Here objects are stripped of their context, rendered in thousands of layers of ballpoint ink—their essential energy magnified on paper—until the viewer is left just looking, just breathing, just being. I draw to stop the mind.

I began Ten Thousand Things that Breathe in 1989 and first exhibited it in early 1996. Since that time, Ten Thousand Things that Breathe has grown to encompass hundreds of works that have been featured in exhibitions at the Drawing Center,Andrea Rosen Gallery, and Josée Bienvenu Gallery in New York City,The Travelling Gallery in Scotland, and the North Dakota Museum of Art, among others. Numerous pieces from this series have also found their way into New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and various important private collections throughout the world.

Ten Thousand Things that Breathe may be conceived of as a tree with many branches. For many years I continually added to this series, strengthening its foundation.Then in 1999, the trunk of the tree began to develop branches.As in my prior work, I would strip an object of its context and imbue it with presence; this time I would reinsert the work within a complex of meanings.This tension between the simple and complex would push my mind to that place where words do not go, so that once again I find myself at the doorstep of Presence.

Among the earliest of such works was the series called Drawer Drawings (1999).To create a drawer drawing I borrow a commonplace object found in a collector’s home and draw it as I would any other. Once finished, the drawing is framed and re-installed in a drawer in the collector’s home. I am sworn to complete confidentiality, telling no one what I had drawn. The prerogative to show the artwork belongs to its owner. The series continues to grow; to date, drawer drawings reside in private collections in Paris, Berlin, London, and Washington, D.C.

Drawer Drawings uncovered a fascination for hidden things. But here was an inherent tension: as an active exhibiting artist, I felt compelled to display my works; however, I instinctively preferred to keep them secret, away in drawers and shelves.To explore this dialogue between the seen and the unseen, I began searching for ways to frame my works in a manner that maintained the drawing’s integrity, while setting up drawers and shelves as appropriate contexts for their hidden presentation. It was only with the creation of the Iraq Memorial (2004) that I arrived at a sufficiently elegant solution to this problem.

Even as I sought to create hidden presentations, the current war forced me not only to express but also to extend myself more publicly. I set to work on a new branch of ballpoint drawings, filling sheets of paper with the names of Iraqi men, women, and children—casualties of war—and drawing commonplace objects over them. The names unwind, an endless sea partially obscured by drawings of objects—pomegranates, watercress, a teacup, a comb—that seem to float in it.Taken from files maintained by human rights activists who try to drive home the true cost of war, the names are written in an upside-down mirror script that veils them from Western eyes.

In time, the Iraq Memorial found its way to Paris where it drew the attention of three important public collections (the Pompidou, Frac Picardie, and the Guerlain Foundation) that sought to acquire the work. Ultimately, however, it was acquired by the Echavarria collection, which is being amassed for a future museum against violence in Colombia.

The Iraq Memorial showed me how I might install drawings in shelves: by drawing directly over printed text.

This discovery made possible the series called Bookworks (2005).These works are essentially Ten Thousand Things that Breathe rendered on books and other printed matter, and as such serve collectively as yet another branch of the tree.

While Bookworks allowed me a means to shelve or hide my works, it provided me with the space to juxtapose one kind of presence—that of printed text and symbols—with that of another—that of my drawing. In rendering commonplace objects whose names and meanings would gradually be diminished in favor of their essential energy, I chose to disregard the meanings embodied in the book’s or printed matter’s textual content.This format paved the way for the differentiated objects that populate Bookworks—various cuts of raw meat drawn in bibles, anatomical parts and nudes in dictionaries, and human ears in library books and filed documents.

Bookworks has been featured in exhibitions in NewYork (Josee Bienvenu Gallery, Leo Fortuna, Mushroom Gallery, Old Westbury) and other cities, including Paris, Brussels, and Miami.

The more recent Library Bookworks (2008) bring my art into the realm of public installation. At year’s end, fifteen libraries will be participating in a permanent public installation in the Philippines.The installation will be heralded by a one-month solo exhibition at SLAB gallery. For the project, I render human ears in library books and produce corresponding photographic reproductions to which the books’ call number labels are affixed.The photo prints, exhibited in the gallery, are essentially maps that disclose the books’ locations.Thus the library becomes a gallery and the gallery a library.

I continue to mine the tension between the private and the public, the silent and the political, the delicate and the intense, through works of extreme simplicity. I am presently at work on a branch called Bloodworks (2006), the only branch that has yet to be exhibited.

Bloodworks consists of ballpoint pen drawings of menstrual bloodstains donated to me by female friends and acquaintances.These come in fragments of loose fabric, bed sheets, underpants. I approach them as I would any other object, drawing them with a ballpoint pen on a blank sheet of paper. I draw until the idea of “menstrual bloodstains” and all related conceptual artifacts dissolve in my mind. Pushing past that, I continue to apply countless layers of ink until this context marked by layers of cultural taboos and gender/sexual politics is imbued with a clear and simple presence. It is my intention to put together a little more than two dozen such works for a solo exhibition.

My art has benefited greatly from a variety of fellowships over the years. My first Pollock-Krasner Fellowship Grant (1998), the UCross Foundation Artist Residency (1998), the Djerassi Artist Residency (1999) and the AT&T Fellowhip (1999) supported the creation of scores of works in Ten Thousand Things that Breathe. In addition, a second Pollock-Krasner grant (2005) helped support the creation of the Iraq Memorial and a few of the drawings in Bookworks.

To date, the simple but intense drawings of objects on a blank page, Ten Thousand Things that Breathe, continue to convey my direct experience of reality. I have put this paradigm through further iterations—Drawer Drawings, the Iraq Memorial, Bloodworks, Bookworks, and all their sub- branches—to reveal the many facets of this singular view of the nature of being. I certainly have my work cut out for me. As Ten Thousand Things that Breathe approaches its 20th year in 2009, I find myself moved to revisit the essential motivations that initially inspired it.What direction this reexamination may take is anyone’s guess. I just follow the work wherever it leads. One thing I do know is that it promises to be a more rigorous look at Presence and Being.

Renato Orara

2008

For over a decade, Renato Orara’s works have garnered international critical acclaim. His works are simple yet extreme. Orara’s ballpoint ink works on paper, meticulously rendered and densely layered, seem to embody a reality that transcends that of the object that serves as his subject.Viewing reproductions of his work is not enough preparation for the astonishing experience of seeing the original work. His works have been featured in exhibitions in many cities including New York City, Paris, Brussels, Basel, and Miami, and are in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and the Museum of Modern Art in NewYork.

Works