The Collection of Jane Ryan and William Saunders

Pio Abad

Curated By Patrick D. Flores

Jorge B. Vargas Museum, Quezon City

Installation Views

About

Jorge B. Vargas Museum, in cooperation with Silverlens Galleries, presents The Collection of Jane Ryan and William Saunders, a major solo exhibition by artist Pio Abad.

Abad employs strategies of appropriation to reveal the social and political significations of objects, unraveling the circumstances in which artworks and commodities are made, presented and exchanged.

A large concrete sculpture of primeval folklore stands at a tangent to its diminutive original source, rendering it a figurine of an original. An array of postcards of a seized and sequestered collection is finally for the taking. And a painting on a miracle of fishes, supposedly by Tintoretto, hangs on a panel papered over by the image of a repeating octopus.

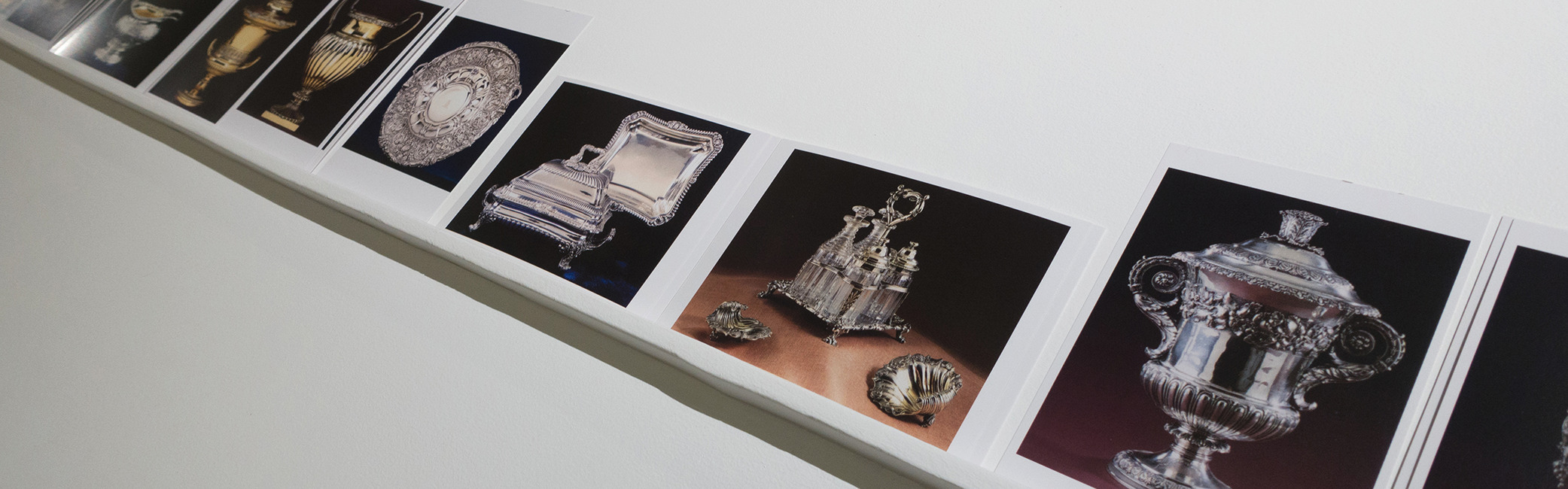

The folklore is Malakas at Maganda, the first man and woman of the Philippine earth, claimed by Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos as their doppelgangers, the genesis itself of a new nation. The sculptor is Anastacio Caedo, a sculptor of classical bent known for historical monuments and commemorative busts. The disputed trove consists of exceptional Regency silver and eclectic European art peddled at Christie’s in 1991. The painting is The Miraculous Drought of Fishes by the Renaissance master Tintoretto, auctioned and then returned on account of uncertain authenticity. And the motif of the hideous mollusk comes from a book titled Some Are Smarter Than Others, which details the breathtaking property of the Marcoses by way of what its author calls “crony capitalism.”

Pio Abad choreographs theses things and the tales animating them to initiate a critical conversation on the discourses of singularity, surplus, and semblance. He looks at them as traces of something sordid, a body of evidence that exhibits morbid symptoms of a possible psychopathology of power.

A large concrete sculpture of primeval folklore stands at a tangent to its diminutive source, rendering it a figurine of an original. An array of postcards of a seized and sequestered collection is finally for the taking. And a painting on a miracle of fishes, supposedly by Tintoretto, hangs on a panel papered over by the image of a repeating octopus

The folklore is Malakas at Maganda, the first man and woman of the Philippine earth, claimed by Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos as their doppelgangers, the genesis itself of a new nation, a new society in the parlance of Martial Law. The artist is Anastacio Caedo, a sculptor of classical bent known for his historical monuments and commemorative busts. The disputed trove consists of exceptional Regency silver and eclectic European art peddled at Christie’s in 1991. The painting is The Miraculous Drought of Fishes by the Renaissance master Tintoretto, auctioned and then returned on account of uncertain authenticity. And the motif of the hideous mollusk comes from a book titled Some Are Smarter Than Others, which details the breathtaking property of the Marcoses by way of what its author calls “crony capitalism;” Here it becomes wallpaper: banal, ubiquitous, all over.

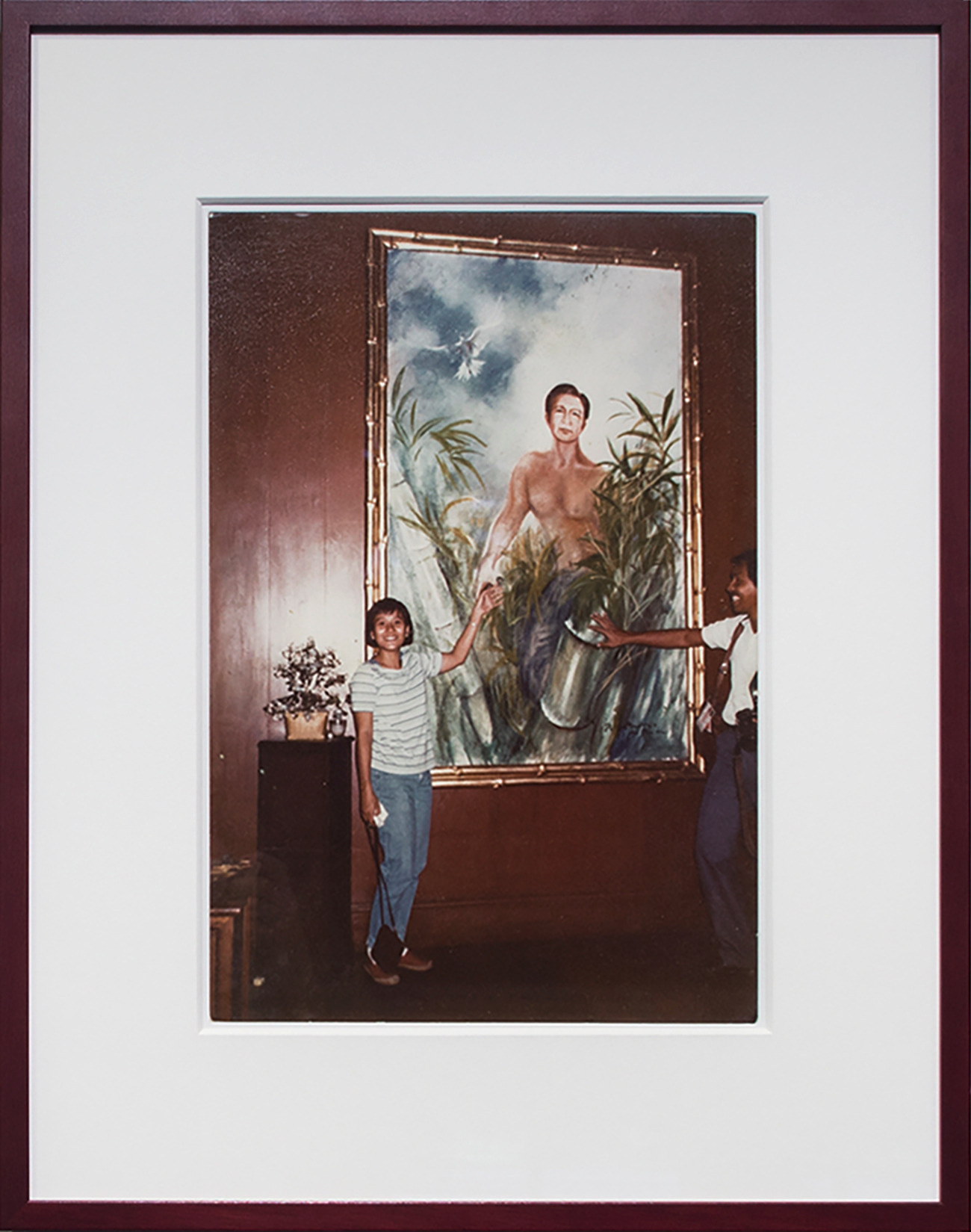

The museum space becomes on keener reflection a hall of the uncanny. A simulacrum seems to emerge in the three likenesses of the Malakas at Maganda iconography that speaks of foundational virility and beauty: the supposed template by Caedo, which is actually a trophy or a commemorative gift given to the collector Jorge Vargas to mark a sports event supported by the soda company 7 Up; the looming replica that dwarfs its model; and the gilt souvenir item bought by the artist in an antique store in a mall. Then there is the archival photograph of the painting of the same subject, taken a few days after the 1986 uprising that deposed the Marcos administration, but this time reincarnated in the idealized body of Ferdinand materializing from a bamboo stalk, out of the rhizome of a grass that gave nature its human life, its creation myth, the basis of labor and capital formation itself and civilization in the long haul.

The uncanny manifests as well in the varied plinths on which these totems rest: the cement base, the pedestal of hardwood, and the round modernist stand. The architectural thinker Gottfried Semper thought of the plinth as a nexus between structure and ground, and in this instance it functions as a point of contact that touches both the artifice and its architecture of appearance, its terrazzo floor mimicking the look of marble. When the light shapes its silhouette, a shadow is cast, another form of trace. The art historian Michael Baxandall conceives of the shadow as a “real material fact, a physical hole in light...(that) has neither stable form nor continuity of existence... the outcome of a relation between light and dense solid.” The shadow in the mind of the artist may well be an allegory of evidence that inflects the “surface of sculpture” that is the opaque, immovable, incontrovertible corpus of formidable wealth and its versions, as it were.

In Abad’s mingling, traces further ricochet, poetically and politically. Consider, for instance, the way in which the pseudonyms of Jane Ryan and William Saunders play out as the cipher of the collection, the very fictitious names used by Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos in their accounts in Switzerland. “Saunders” is particularly intriguing because Marcos had appropriated it as a soldier in World War II, the event that putatively gave him the equally contested medals of valor. This trace is finally disseminated through museum postcards that, instead of describing the objects art-historically, detail in forensic terms the trail of a pillage. In 1987, the Metropolitan Museum of Manila, a museum that Imelda Marcos built to exhibit “international art,” in cooperation with the Presidential Commission on Good Government, created by the revolutionary government of Corazon Aquino to secure the ill-gotten possessions of the Marcoses, presented the exhibition “Paintings by Old Italian Masters.” Some of these pieces may have been auctioned, the proceeds of which had funded the agrarian reform program of the successor government of the same political class. It is curious how the elites would liberate peasants from their bondage through the capital amassed in art.

Abad choreographs these things and the tales animating them to initiate a critical conversation on the discourses of singularity, surplus, and semblance. He looks at them as traces of something sordid, a body of evidence that exhibits morbid symptoms of a possible psychopathology of power. He is interested in the artifice and its claims to originality, be it art that is not replicable or a myth that founds a world or a Biblical fabulation of an unbelievable haul of fishes. A foil to this is its corruption, the dissembling of identities to conceal a treasure as in the case of the Hollywood-sounding aliases of Jane Ryan and William Saunders, which evoke illusions of arriviste royalty and courtly culture. Abad confides that this undertaking is a turning point in his relationship with objects in terms of the directness with which he gets hold of them as if to disconfirm their elusive guises and to hold them to their word.

From this welter of propaganda and kitsch, wealth and aspirations to it, fraud and authenticity, memorial and memento, vanity and nation, fantasy and banality, “patronage and pornography” arise contending entitlements to oligarchies that lead to a lot of loot, handiwork of either Cold War strongmen or of the progeny of nineteenth-century feudal lords and pioneer monopolists. It is all at once loony and sad and lasting.

Words by Patrick D. Flores

August 2014

Pio Abad’s work looks at the intersections between histories of the decorative and the political. Through installations, prints and photographs, his work sets up juxtapositions that mine the relationships between things and events; between the anecdotal and the allegorical. Objects and images are reconstructed or re-presented in order to activate their relationship to individuals, ideologies and narratives.

Abad was born in Manila, Philippines in 1983. He started his fine art studies at the University of the Philippines and received a BA (hons) in Painting and Printmaking from Glasgow School of Art and an MA in Fine Art from the Royal Academy Schools. He was one of the finalists for the Dazed and Confused Emerging Artist Award in 2012. Abad has been shortlisted for the Ateneo Art Awards (Manila) in 2013 and 2014.

Works