Behold A City

Ryan Villamael

Silverlens, Manila

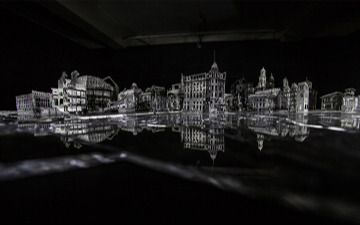

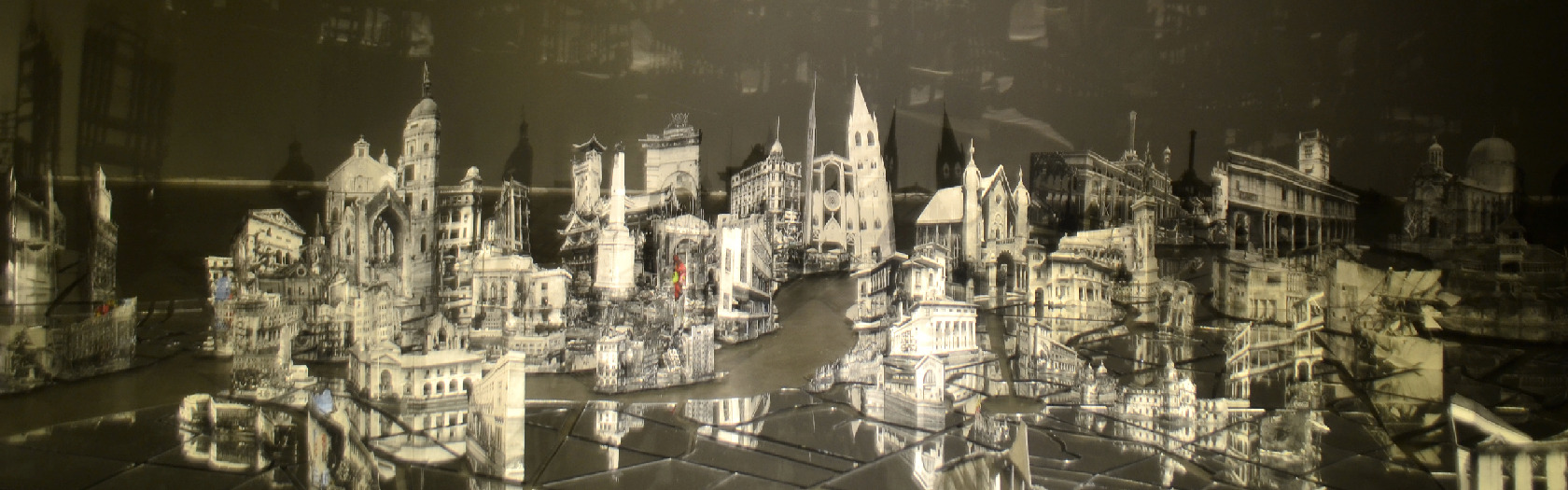

Installation Views

About

Silverlens is pleased to present Behold A City, a solo exhibition by Ateneo Art Awards 2015 winner Ryan Villamael.

Cutwork meets history. Behold A City is Ryan Villamael’s foray into the realm of photography as material and image source for his art. He pushes his métier by tracing his blade along the contours of built heritage pictures, as a way to reclaim what war has lost or what little sense of patrimony has been sacrificed in favor of the vulgar remedies that come with the upkeep of a dysfunctional metropolis aspiring to be modern.

Much has been written about pre-war Manila as one of the most picturesque capitals in the Colonial Southeast. The city was a brew of Art Deco, Baroque, Euro-American Revivalist architecture and planning across the civic, commercial and domestic spheres of peacetime life. That this was set against a tropical context complemented by warm people enhanced its unique charm.

In the Second World War, Manila suffered enormous destruction - second to Warsaw - so much so that America’s 803 million dollars in rehabilitation aid until 1953 could not bring back the city to its former state.

The photographic images of Manila before and after the war are a study in contrast. What were once spacious tree-lined streets dotted by monuments and promenades, or else flanked by colonial and modern edifices, have been reduced to charred structural carcasses of their former selves. Across the peaks and valleys of rubble, Manila was a charred landscape straight out of dystopian movie.

What has become of the city seventy years since liberation? Exactly what is meant when the eponymous utterance is exclaimed? What has been neglected, despoiled or demolished in the name of development? Is the idea - the city is the reflection of its citizens – an ugly reminder or a simplistic aphorism?

In his role as itinerant observer of places, the artist conjures his own Manila. He reframes it as a historical-artistic imaginarium - a space to recompense for the quixotic task of preserving what little has remained. It is his playground to neutralize ersatz quick fixes for irreparable damage that breed kitsch sensibility. It is his gesture to rectify the inability to overcome the hurdles arising from the complex issues surrounding built heritage.

This space is not a constructed representation of an ideal or utopia. Neither is it the complete reverse of perfected form.

Akin to a movie back lot, its obverse sides are not architectural façades of anything but decorative pattern; a vacuity despite an apparent fullness. It is a pop-up without its book host. It is not divorced from the physical space it occupies. Instead, it is the juxtaposition of many spaces: internal and external, past and present; a space of sublimity and tackiness, a baptistery and a graveyard. This is a place of shadows and pictures, actuality and reflection; the locus of economics and vision.

Set up over a mirrored map that doubles it visually, this place is city that floats like a ship, “... a place without a place, existing on itself, closed in on itself, but given over to infinity...” the way ships go out to sea from port to port, to search perchance for colonies and treasures.

There is a practice wherein keys to the city are given to exemplary citizens or guests for their civic contributions. Being symbolic, the keys do not really unlock any door or gate. In medieval times whence it was derived, giving keys to the poor signified their freedom from serfdom. The giving of keys today is a gesture to signify that the recipients are free to come and go as they wish.

In this show, the artist does not only bestow the key of his city to the viewer. In more ways than one, he also gives it to himself. He does in order to be free of a helplessness that stems from the neglect and general apathy towards history and built heritage, whereby nostalgia is a convenient palliative.

Words by Leo Abaya

Ryan Villamael (b. 1987) is one of the few artists of his generation to have abstained from the more liberal modes of art expression to ultimately resort to the more deliberate handiwork found in cut paper. Villamael has been included in several group shows while still pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Painting from the University of the Philippines up to the time of his graduation in 2009. Since then, his works have been shown both locally and abroad which include Singapore, Hong Kong, and France.

He is a recipient of the Ateneo Art Award in 2015 and the three international residency grants funded by the Ateneo Art Gallery and its partner institutions: La Trobe University Visual Arts Center in Bendigo, Australia; Artesan Gallery in Singapore and Liverpool Hope University in Liverpool, UK.