Epilogue

Ryan Villamael

Silverlens, Manila

Works

About

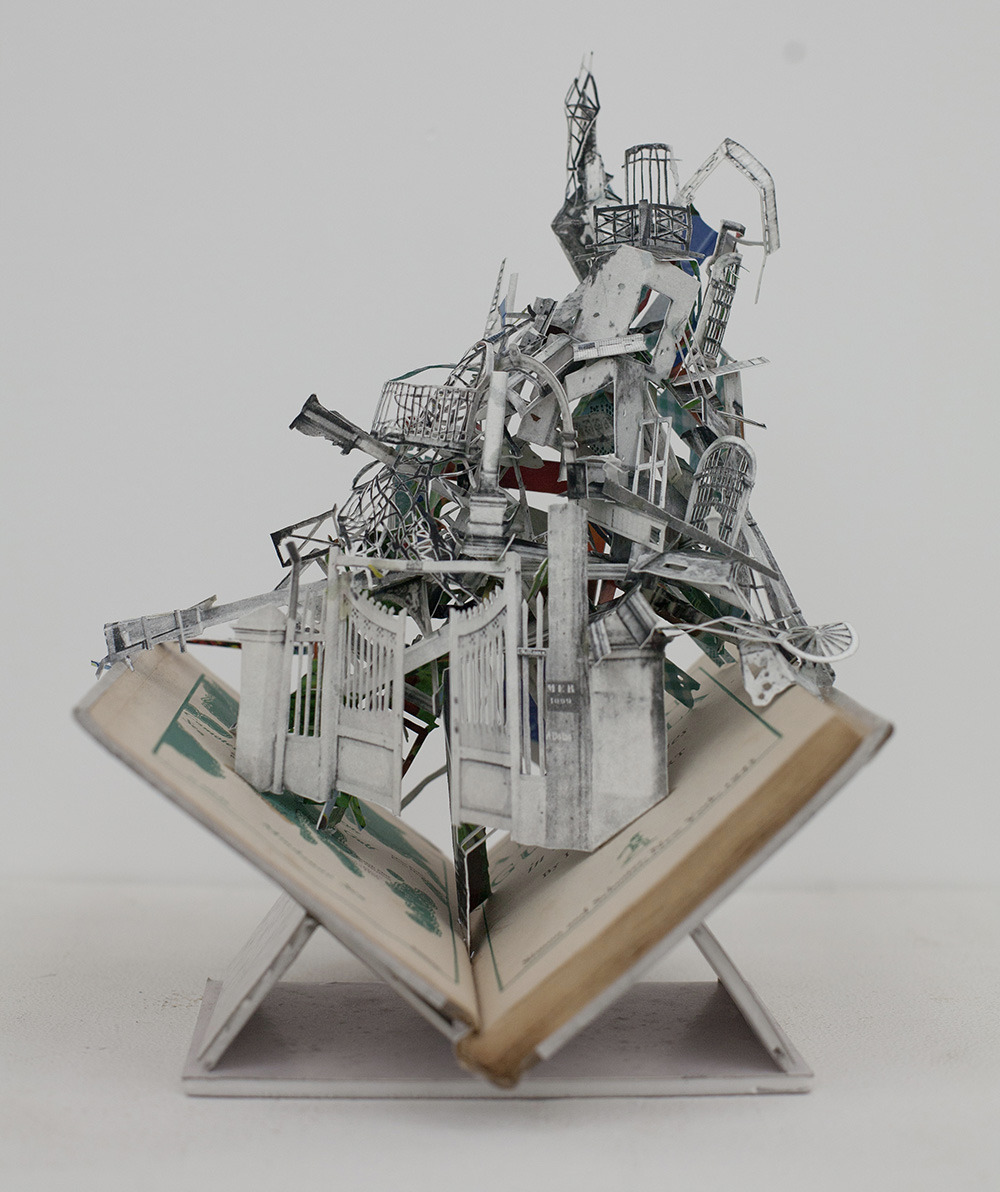

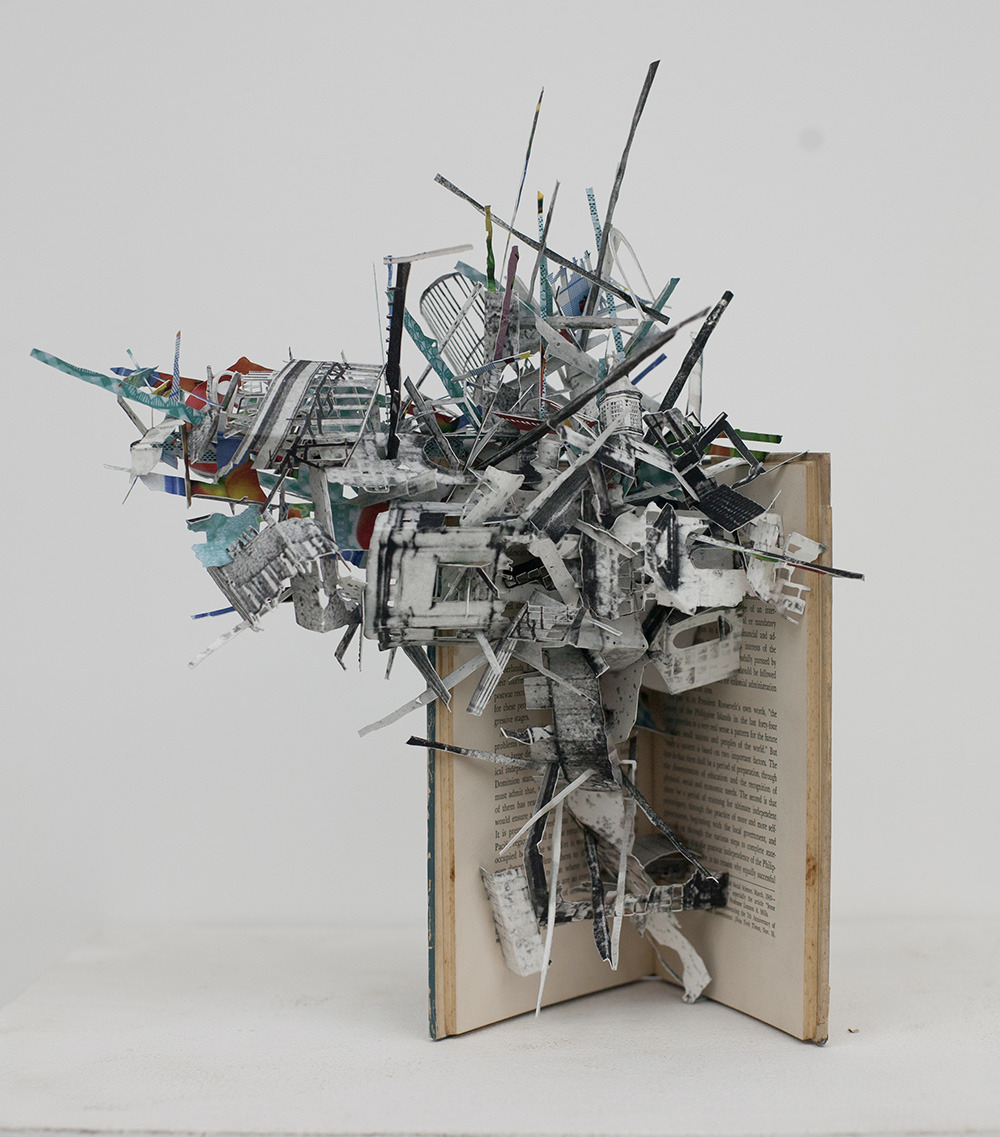

One naturally tends to gravitate towards Ryan Villamael’s work— endless sheets of paper, cut and guided into shape by his care- ful hands—the meticulousness of which speaks of both his skill and his patience. The beauty is unmistakable, but Epilogue is an invitation to look closer, to pay attention, and to discover narra- tives—more open-ended stories than overt commentary—lurking in the intricacies of what seem to be blooming bouquets and otherworldly machinery.

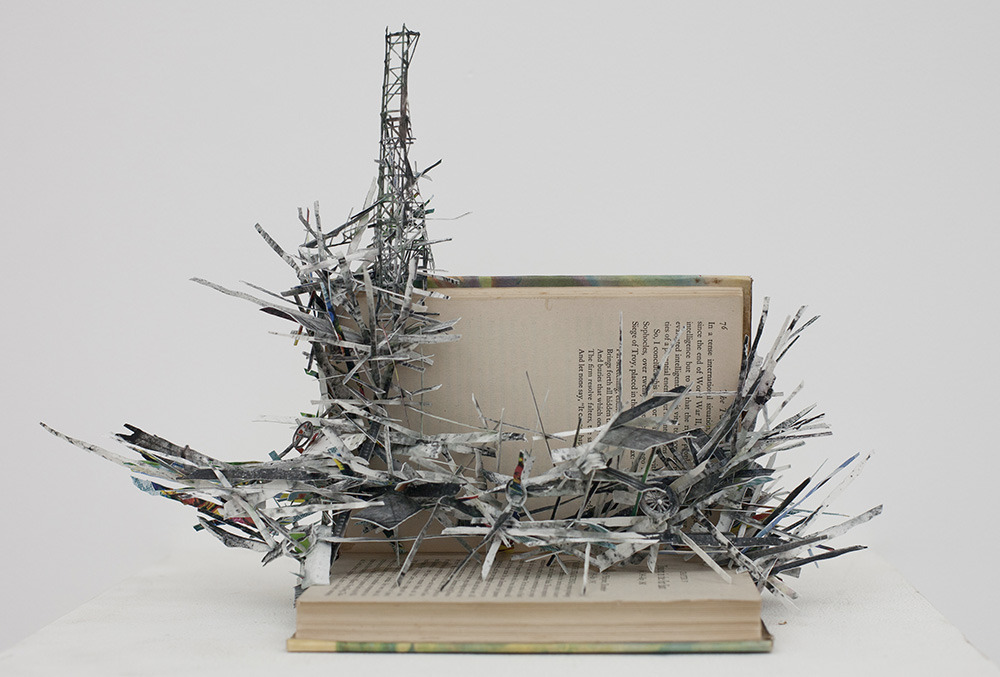

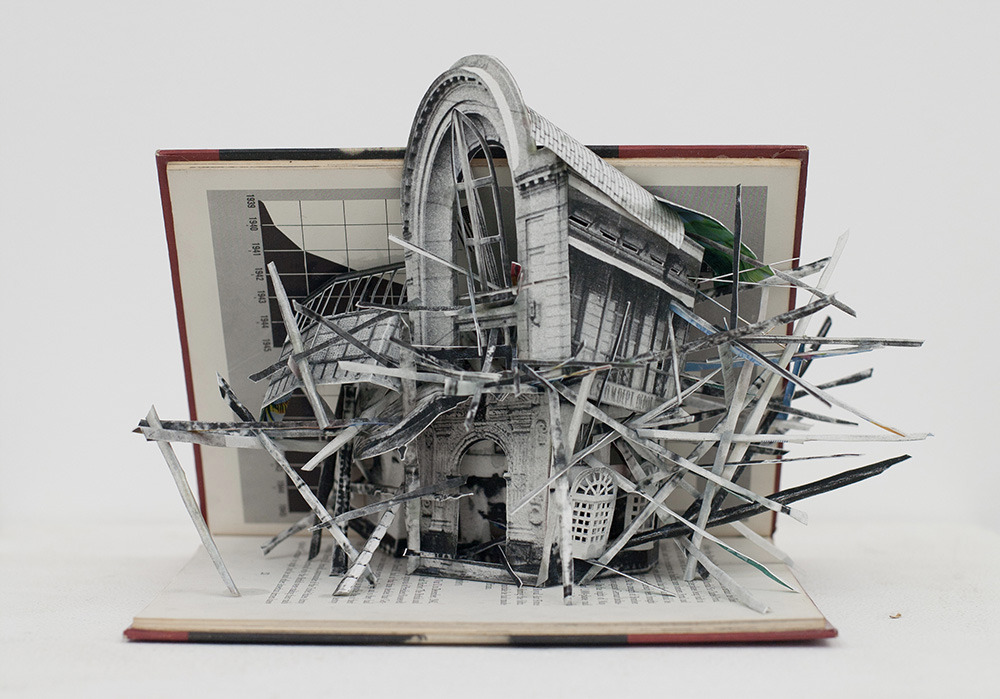

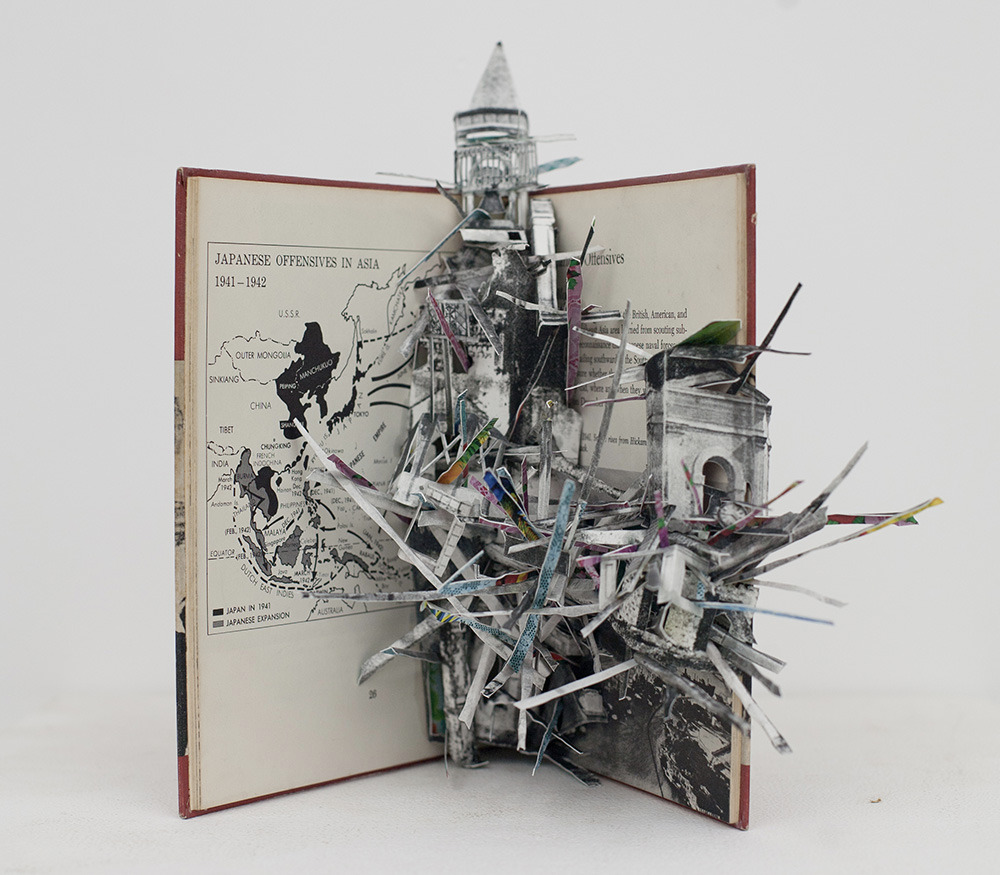

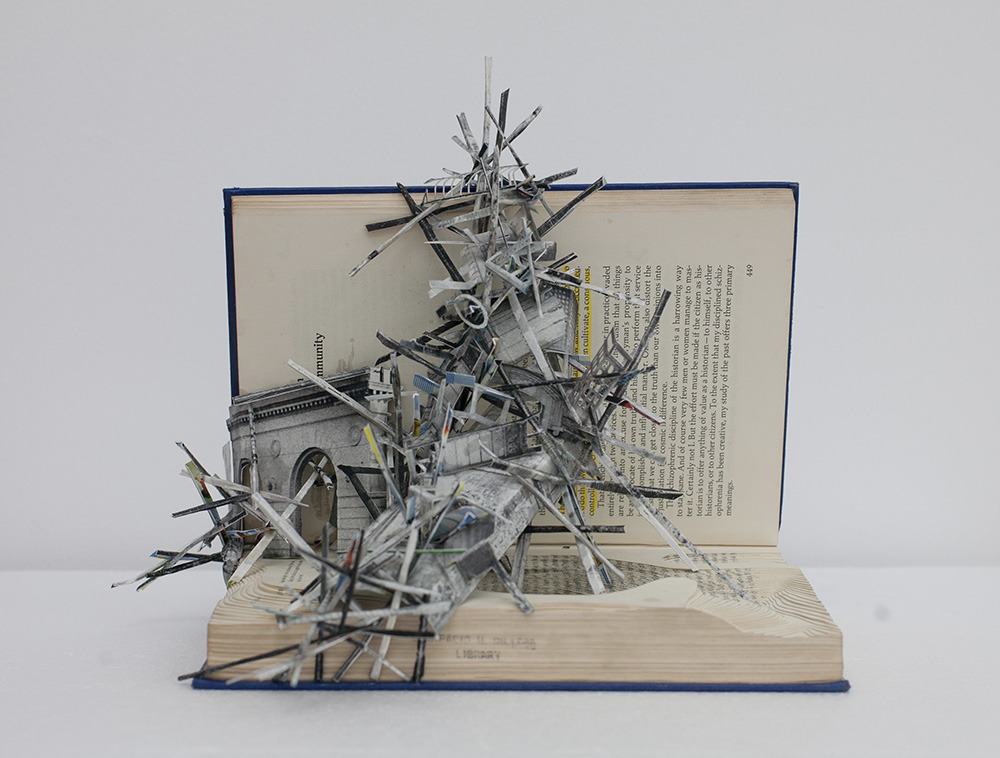

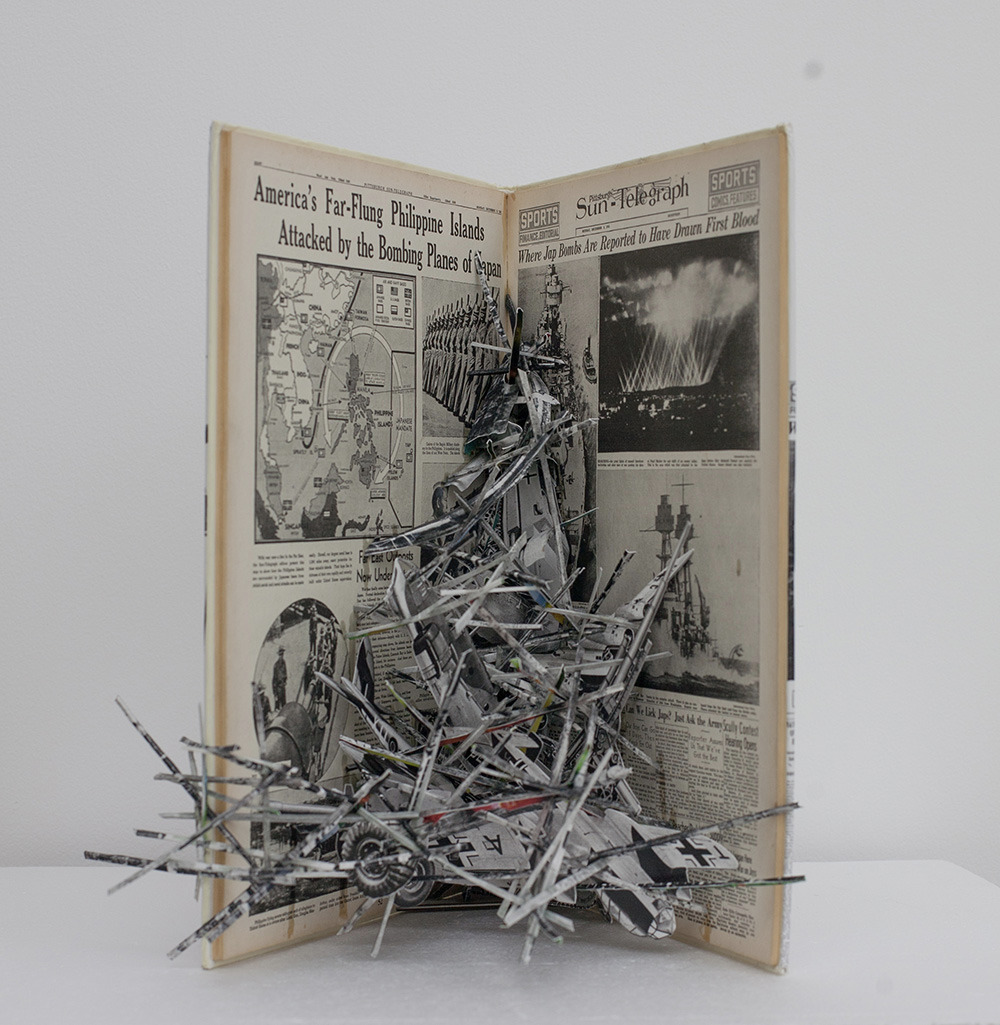

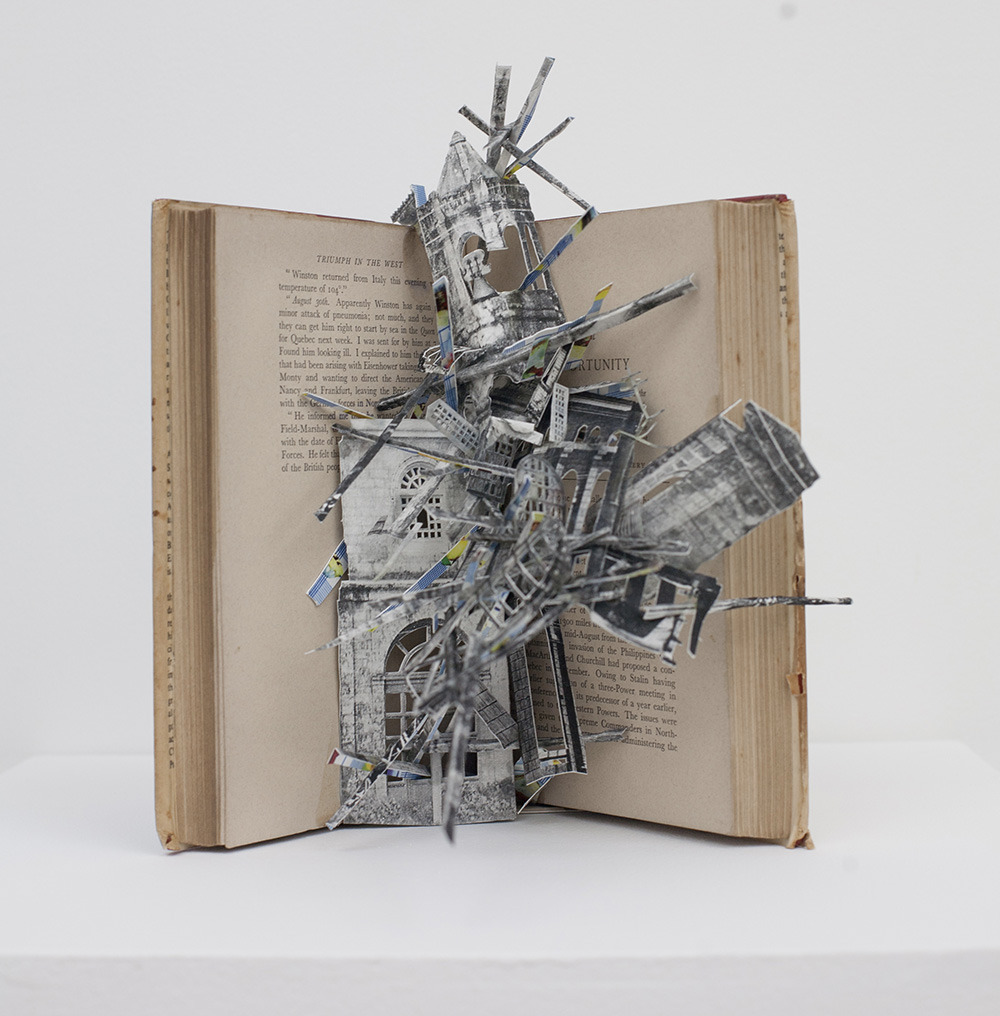

In Epilogue, several paper structures grow and spill out of old books on historical victories and defeats, specifically on the post-World War II of the Pacific, carefully collected by the artist on numerous trips to antique shops, book sales, and garage sales over the years. The subject is an interest recently piqued by the current rapidly shifting political climate, and this show is the artist’s response to the construction of history and his deliberate action towards both the expansion and cohesion of his personal oeuvre.

The result is sculptural, with Villamael’s cutouts rising above the flatness. The construction is more complicated than the paper and felt cutouts early on in his practice. Now, cutouts continue to grow from the books. In making Epilogue, Villamael needed to employ more than a blade and involve more than the act of cutting away, an action that requires the measured care, precision. There is patience in action that he says feels like meditation and therapy.

For this show, Villamael adds on to his material, rather than just removing, a practice he began with “Imperium,” from his 2014 solo show with Silverlens, and 2015’s “Epilogue: Gardens of Eden” and “Epilogue: Ruins of Empire,” shown in Secret Archipelago in Palais de Tokyo, Paris. For this series, however, he takes structural liberty in rebuilding the ruins of Old Manila—aggressive and almost vio- lent remixed remnants of photographs used in his previous show with Silverlens, Behold a City, rather than taking paper refuse from the book itself—within the confines of selected texts on the Pacific War, notably with West-leaning narratives.

Coming back home to Manila from the tail end of the year-long round of residencies (from his win at Ateneo Art Gallery in 2015) Villamael took part in in 2016, as well as his landmark exhibitions at Palais de Tokyo and 2016’s Singapore Biennale, Villamael, with Epilogue, marks a global awareness of sorts—a peek into West- ern histories and narratives, resulting in his attempt at taking hold of these stories and telling our own. The current similarities of the tensions leading up to the World War II are bleak and ter- rifying in their parallelisms, and Epilogue feels like a quiet revolt against what feels like history’s inevitable cycle.

The pieces, a total of 10 books in varying sizes, broken open to reveal something other than the text written inside, contain structures that are visually precarious, but simultaneously persistent and insistent in their desire to break away from what often feels like propaganda. The rebuilt ruins look like they’re trying to escape; they’re the truths that refuse to be buried in narratives that others have written and made up. The books exist to say one thing, often from the perspective of the victors, but Villamael’s structures, which are made from photographic evidence of what transpired, exist to say something else that’s true.

The closer look affords the viewer something beyond skill and craft, that is, a story, or a version of it. Villamael’s attempt at telling them—in the absence of perceived histories, propaganda, and personal feelings or biases—involves the act of opening books. And in place of words, there is a collection of images, amalgams of “triumphs and decay,” the resulting stories framed by whoever is reading the images and making the connections, and so, different with each gaze. The woven narratives from these books are as precarious in their “trueness” as Villamael’s structures look.

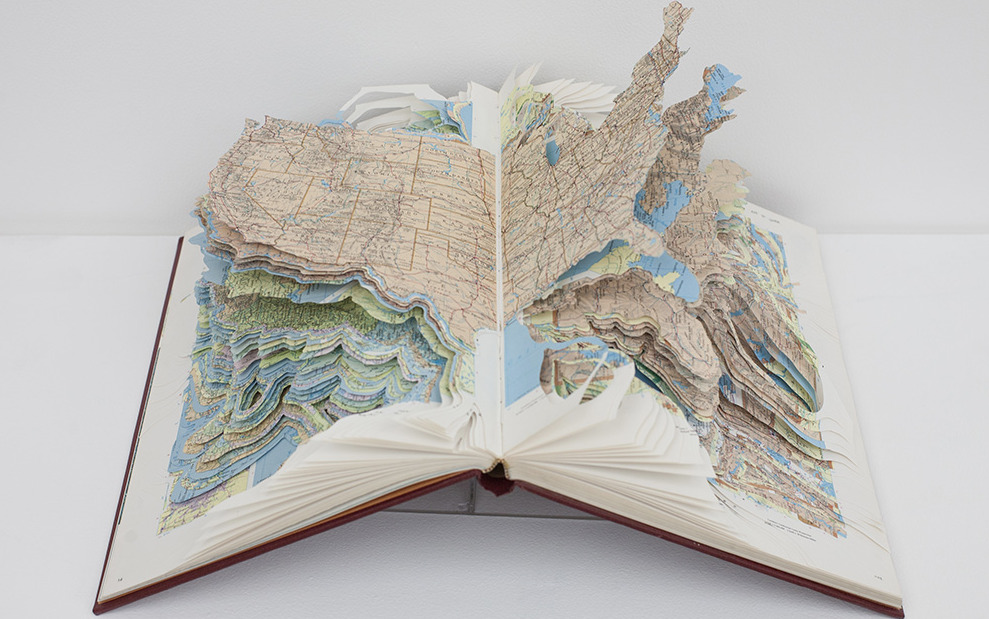

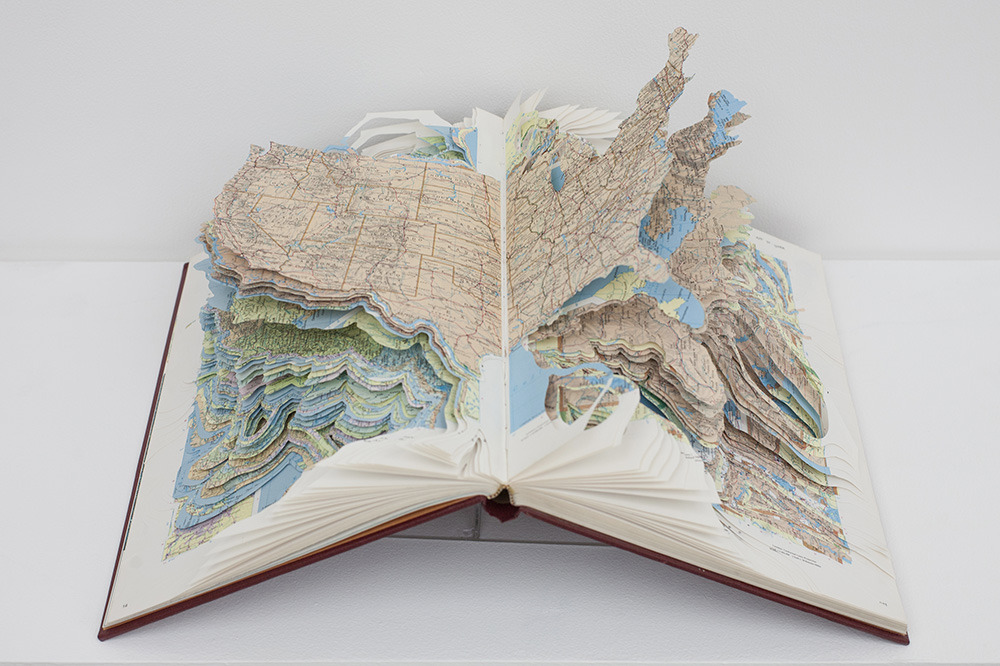

One piece, “Index 10,” shows a map of the United States span- ning the entire open spread, devoid of Villamael’s reconstruction of Old Manila’s ruins. It is the show’s quiet centerpiece. In “Index 10,” Villamael does without the building up—the excavation itself already turning the piece sculptural.

Without the superimposed paper structures, it becomes, then, a form of introspection, a looking within itself to get at the story. In a way, it insists that incisions aren’t bad; that the inherent cuts within history perhaps shouldn’t be hidden away in meaningless messages say little of what really happened. Propped open, with its many layers fanned out, “Index 10” feels like a punctuation to Epilogue, an invitation to tell stories as they are. There are no “ugly truths” desperate to escape, and even with all of the pages’ injuries, one is compelled to see the beauty of all of it.

Epilogue is an expression of what comes after, a study of the framework of what only appears to be the truth, rather than Vil- lamael’s straightforward reportage of facts. It operates on the lev- els of suggestions and connections, leaving the actual story to be determined by whoever gazes upon his wordless tomes. The result is something like a shifting archive of stories and artifacts, each version of it created by the complexity of different perspec- tives, likely only connected by this shared experience of looking at the same objects, each resulting narrative different despite be- ing told the same one.

Words by Carina Santos

Ryan Villamael is one of the few artists of his generation to have abstained from the more liberal modes of art expression to ultimately resort to the more deliberate handiwork found in cut paper. While his method follows the decorative nature innate to his medium of choice, from the intricately latticed constructions emerge images that defy the ornamental patchwork found in the tradition of paper cutting, and instead becomes a treatise of a unique vision that encompasses both the inner and outer conditions that occupy the psyche—which range from the oblique complexity of imagined organisms to the outright effects of living in a convoluted city.

Villamael has been included in several group shows while still pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Painting from the University of the Philippines up to the time of his graduation in 2009. Since then, his works have been shown both locally and abroad, which include Singapore and Hong Kong, and has staged three solo exhibitions to this date. Although his persistence in sustaining a discipline more often subjected to handicraft has been evident from his works, Villamael maintains that his primary interest lies rather in the conceptual significance of craft in the process of creating contemporary art, and continues to recognize the possibility of how his works can still evolve under this light.

He is a recipient of the Ateneo Art Award in 2015 and the three international residency grants funded by the Ateneo Art Gallery and its partner institutions: La Trobe University Visual Arts Center in Bendigo, Australia; Artesan Gallery in Singapore; and Liverpool Hope University in Liverpool, UK. He is participating in the current Singapore Biennale.