Frieze London, Woven - Pacita Abad: Immigrant Series

Pacita Abad

Booth W2, Frieze London

About

SILVERLENS is proud to participate in the Woven Section of Frieze London 2019 with the solo presentation of Pacita Abad’s Immigrant Experience series. This is the first time Silverlens will be participating in Frieze London and the first posthumous exhibition of Pacita Abad’s work in London.

It is travel that prospects form in Pacita Abad’s oeuvre. Until her death in 2004 in Singapore, Abad spent her life traveling place to place, always finding time to set up her studio—wherever she stayed, Abad made art. The Alkaff Bridge in Singapore, one of her last works before her death, is a testament to such a practice that is itinerant but always manages to take root. Abad's itinerary is one shaped by a subjectivity steeped in the complexities of a worldly womanhood: the pedigree of a political family from the island province of Batanes in the northern Philippines, the feminized labor of sewing as heirloom and source of livelihood in her first few months in San Francisco, and the travels that she has done as wife to a development economist. While hers is a peregrine practice the trajectory of which is enabled and motivated by a particular form of capital and a specific subject position for the most part unencumbered by economics, in her artistic practice and career, a particular personage is recognized: a woman entangled in relations of labor and power who somehow manages to unravel for herself a room of one’s own.

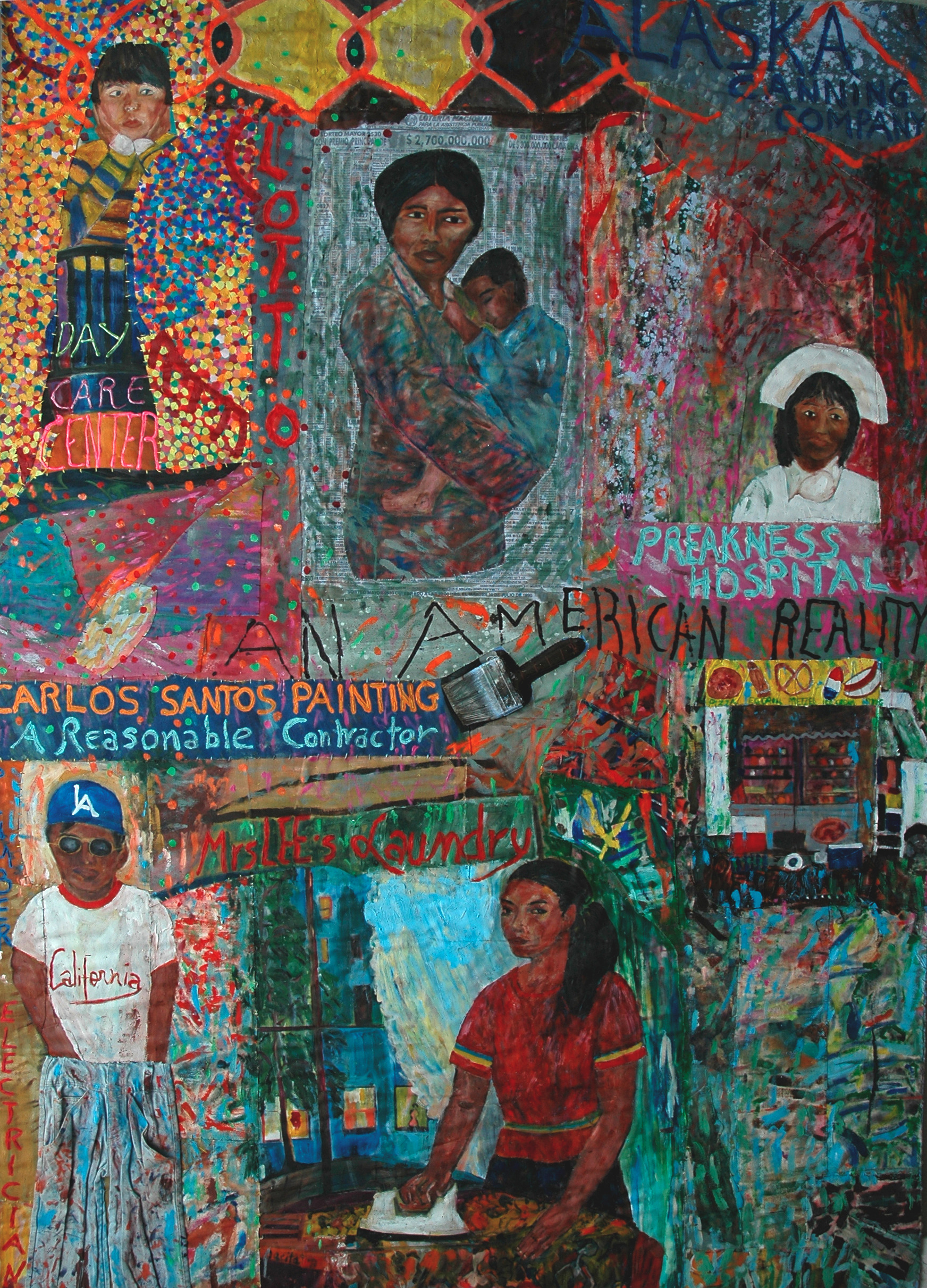

From a revisiting of Abad's works in A Million Things to Say (Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, Manila, 2018), SILVERLENS’ Frieze London presentation attempts to consider her prolific and pioneering work in textile, particularly her trapunto paintings from Immigrant Experience, a selection from the early 1990s. It is by way of the innovation of the trapunto, a technique wherein fabric is padded and given tectonic quality, that textile becomes at the same time surface and dimension. This technique thrives in its intimacy with painting. Abad considered herself first and foremost a painter: after painting canvas, she then quilts and hand sews embellishments onto fabric. Of interest in this particular series is how it became a literal afterlife of her social realist persuasions. A number of works in the series were produced by “cutting up, collaging, and repainting” her older social realist paintings that focused on issues of global minorities. It is in this moment that the social realist attitude is imbibed with cosmopolitan aspiration, a trajectory that is specific to Abad and her life as an immigrant in the United States. This aspiration is an ethic that threads through her quilts and bears out an interfacing with different contexts. It imbues Abad's work with a patient solicitude that discerns a common humanity in what she identifies as “a fabric of nationalities that combines many threads of sizes and colors."

In Abad's textiles, the immigrant's experience is kaleidoscopic and complex. A range of techniques nimbly coaxes material; the labors of handiwork and attention to each stitch, piece of pattern, and choice of color play out astutely. Her way with fabric evokes the simultaneous overwhelming strangeness of new places and their dizzying splendor, such as in You have to blend in, before you stand out (1995). In L. A. Liberty (1992), a woman emerges from radiating strips of color, her garment graphically ornamented, hair of yarn, ornaments of plastic buttons and specks of mirror. She is Lady Liberty, woman of color and immigrant, her hand raising a torch for her fellows. Abad's Immigrant Experience exemplifies her poetics at its most articulate and calibrated, a culmination of her artistic prospects. Here social critique is sharpened and complicated by an implication of the self in the experience being mediated, such as in the work If my friends could see me now (1991). In Abad's works, the immigrant is both exemplary and commonplace. In How Mali lost her accent (1991), the trajectory of immigrant experience is recognized as an attainment of equality through the divestment of cultural identifications or marks of difference. In works like Korean Shopkeepers (1993), the immigrant is among her folks—the trope of the alienated immigrant is troubled by rendering it as an experience shared by many, displacing the narrative of singularity and isolation usually accompanying stories of migration with a narrative of shared suffering and common humanity. The immigrant is exemplary for the demands and desires that she is forced to address to ratify her person in a context aside her own. Meanwhile, the immigrant is typical in that her experience encompasses. In a work such as The village where I came from (1991), Abad alludes to rootedness at the same that she intimates leave-taking and an unravelling of a life outside sites of belonging. In this simultaneity, Abad offers an articulate grasp of the complexity of the immigrant experience. Found in Abad's Immigrant Experience is a sympathy that casts humanity as cosmopolitan, a sympathy encompassing, complex, and ever generous.

Text by Carlos Quijon, Jr.

Works