About

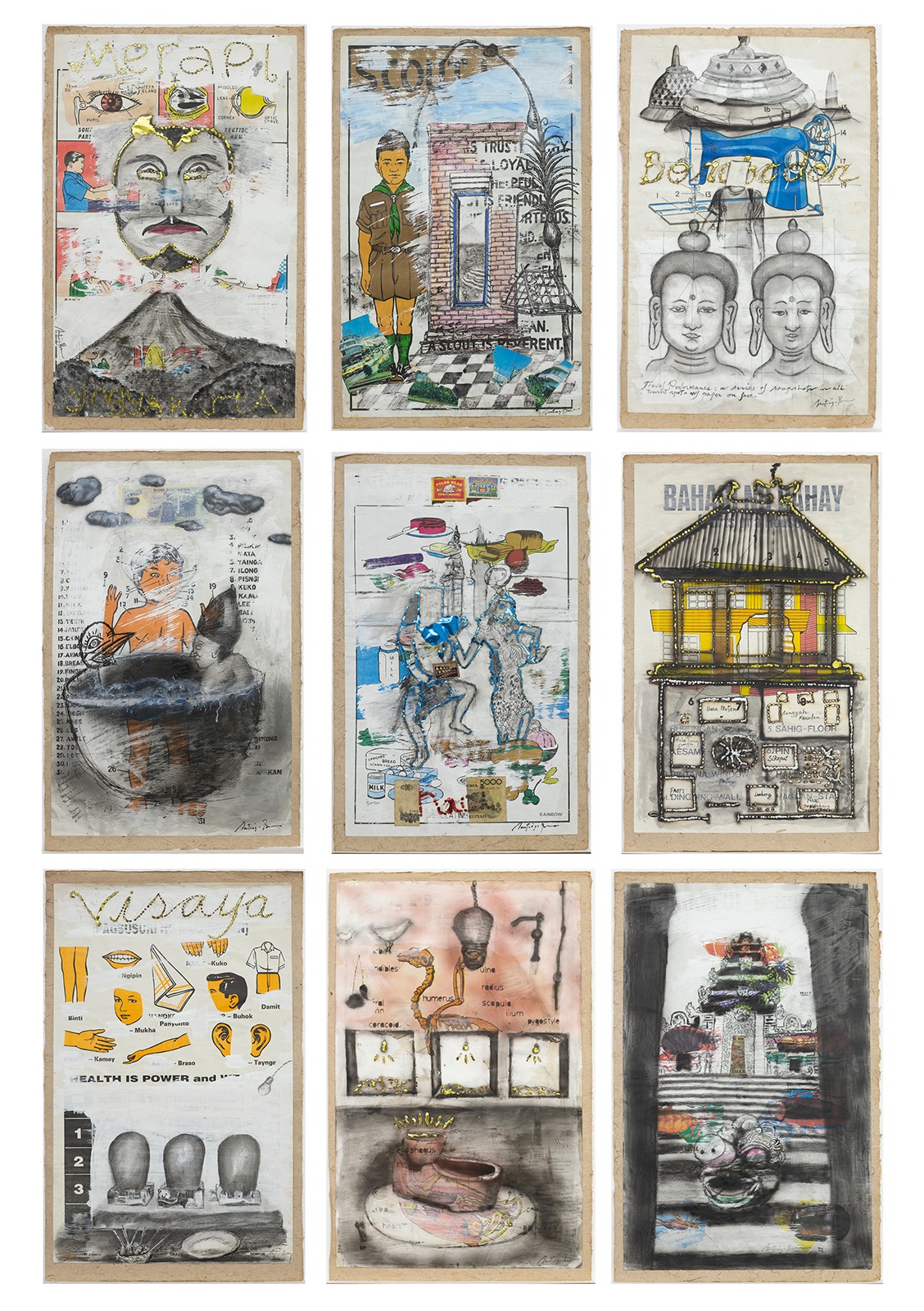

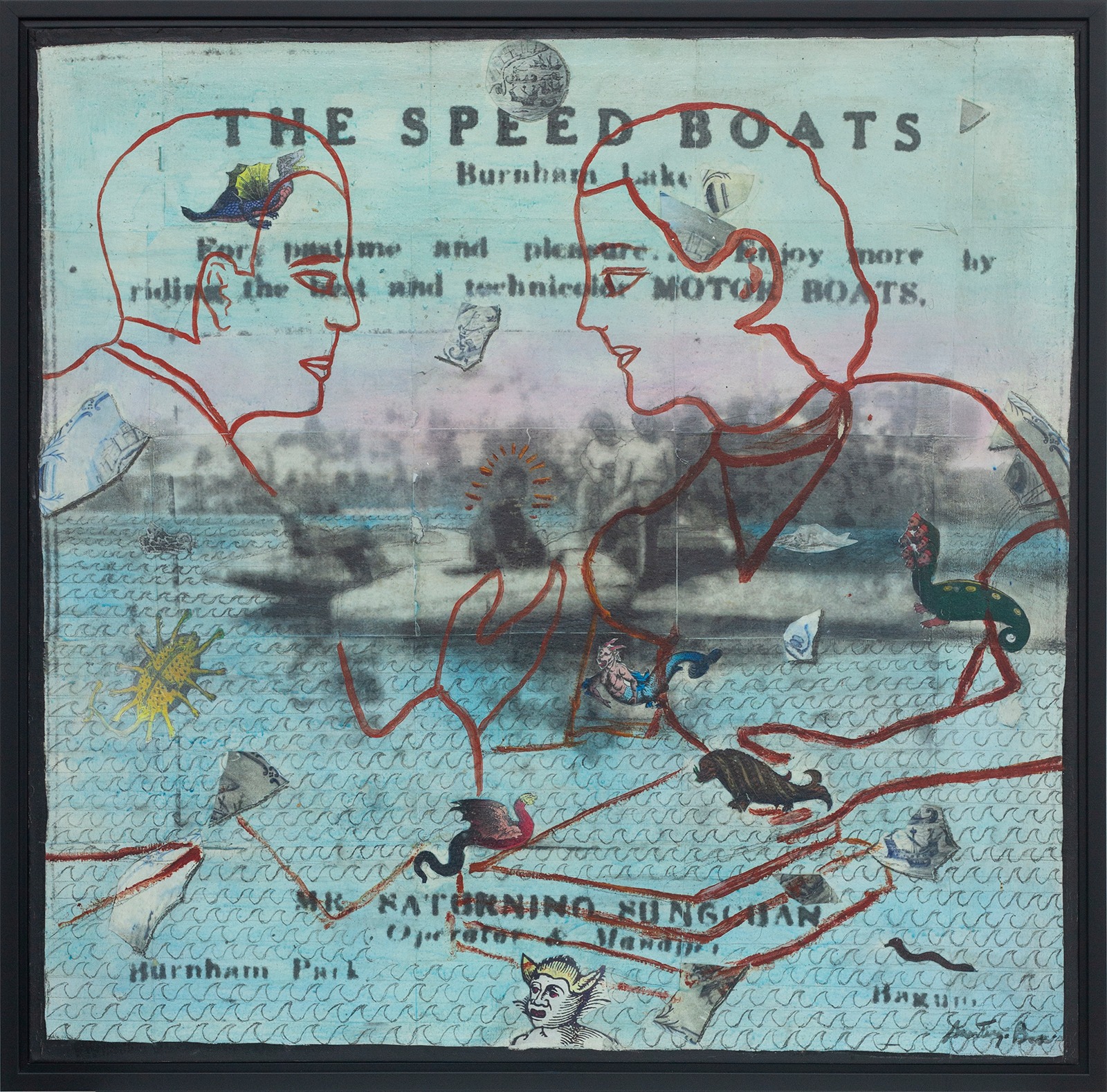

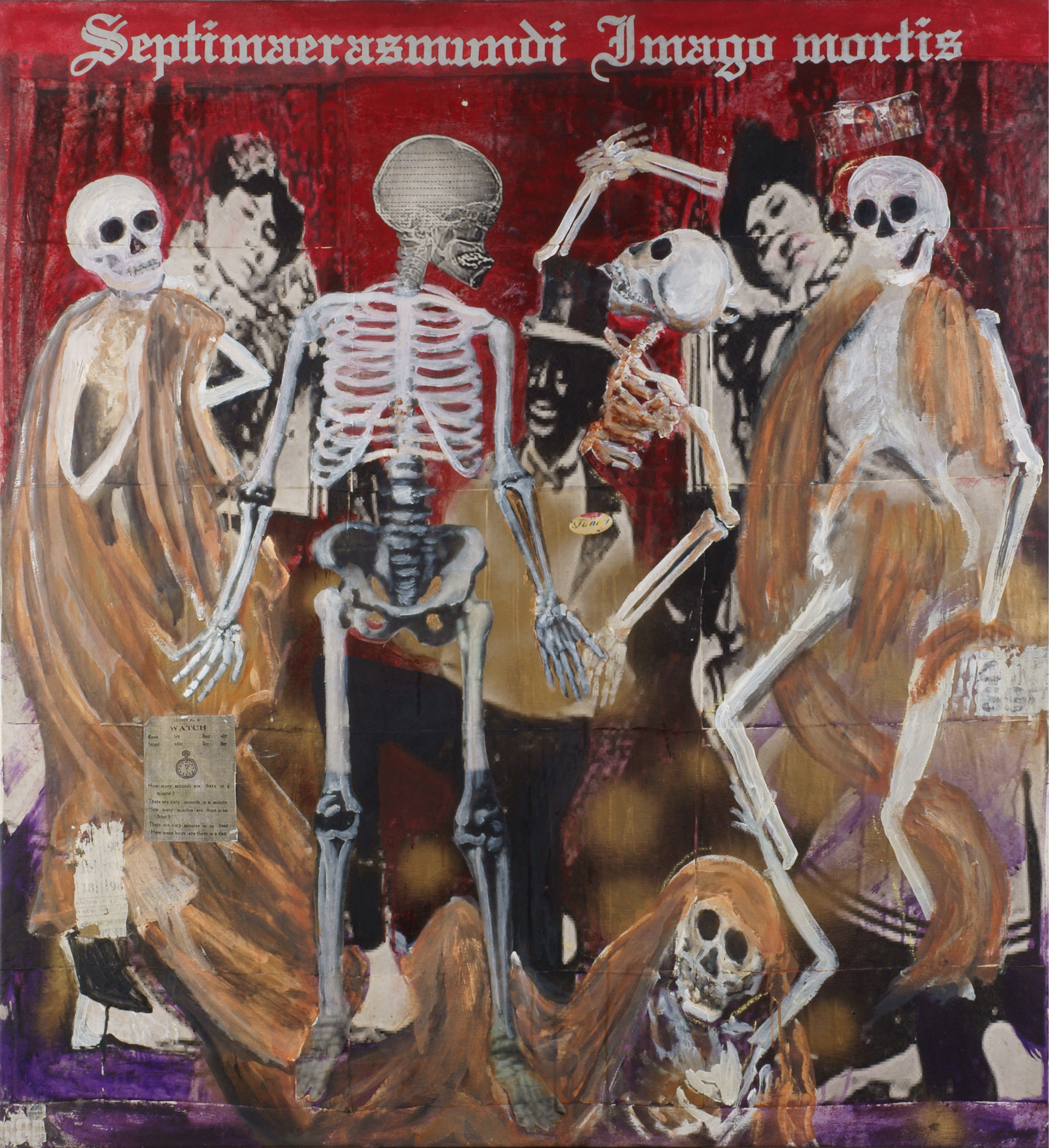

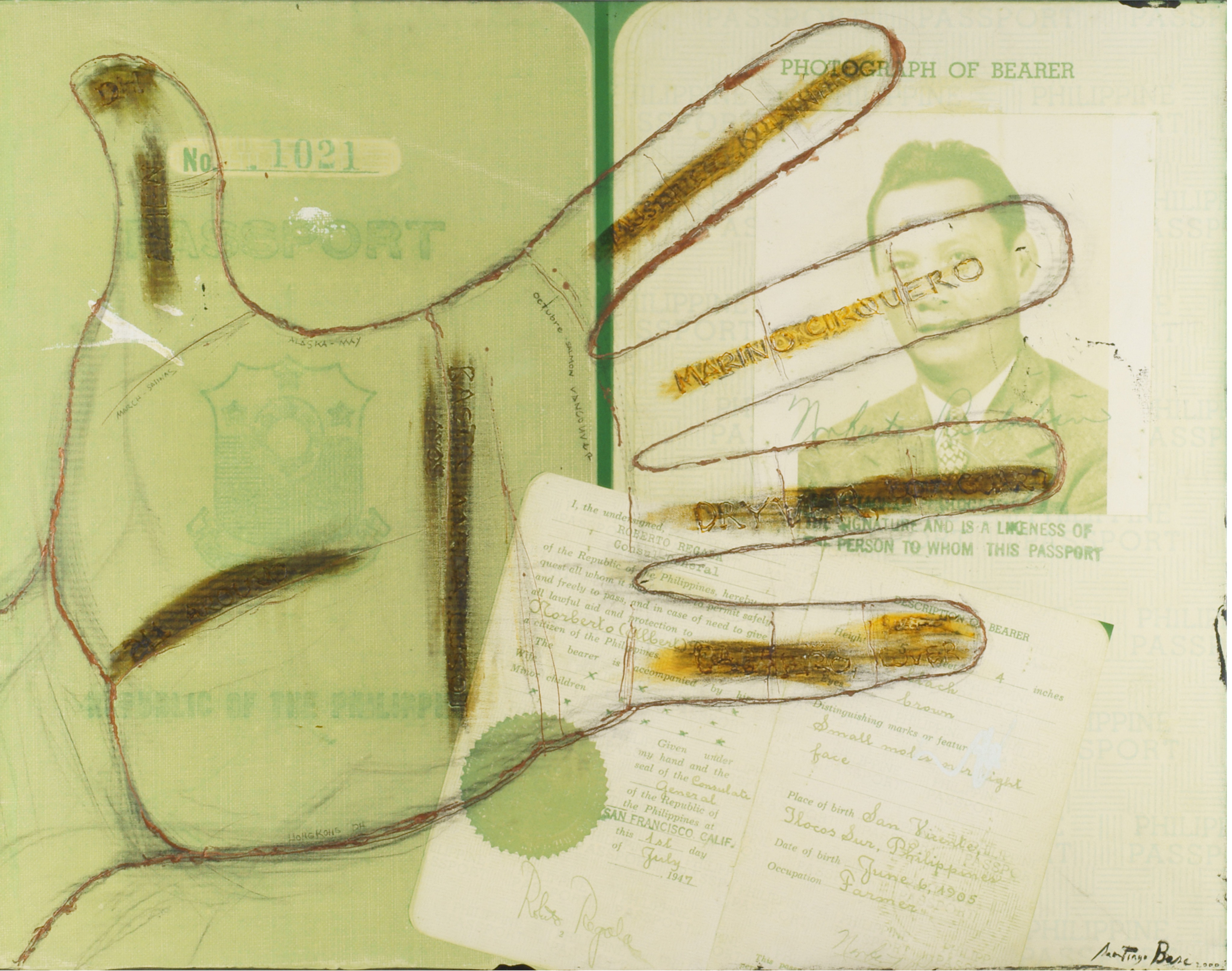

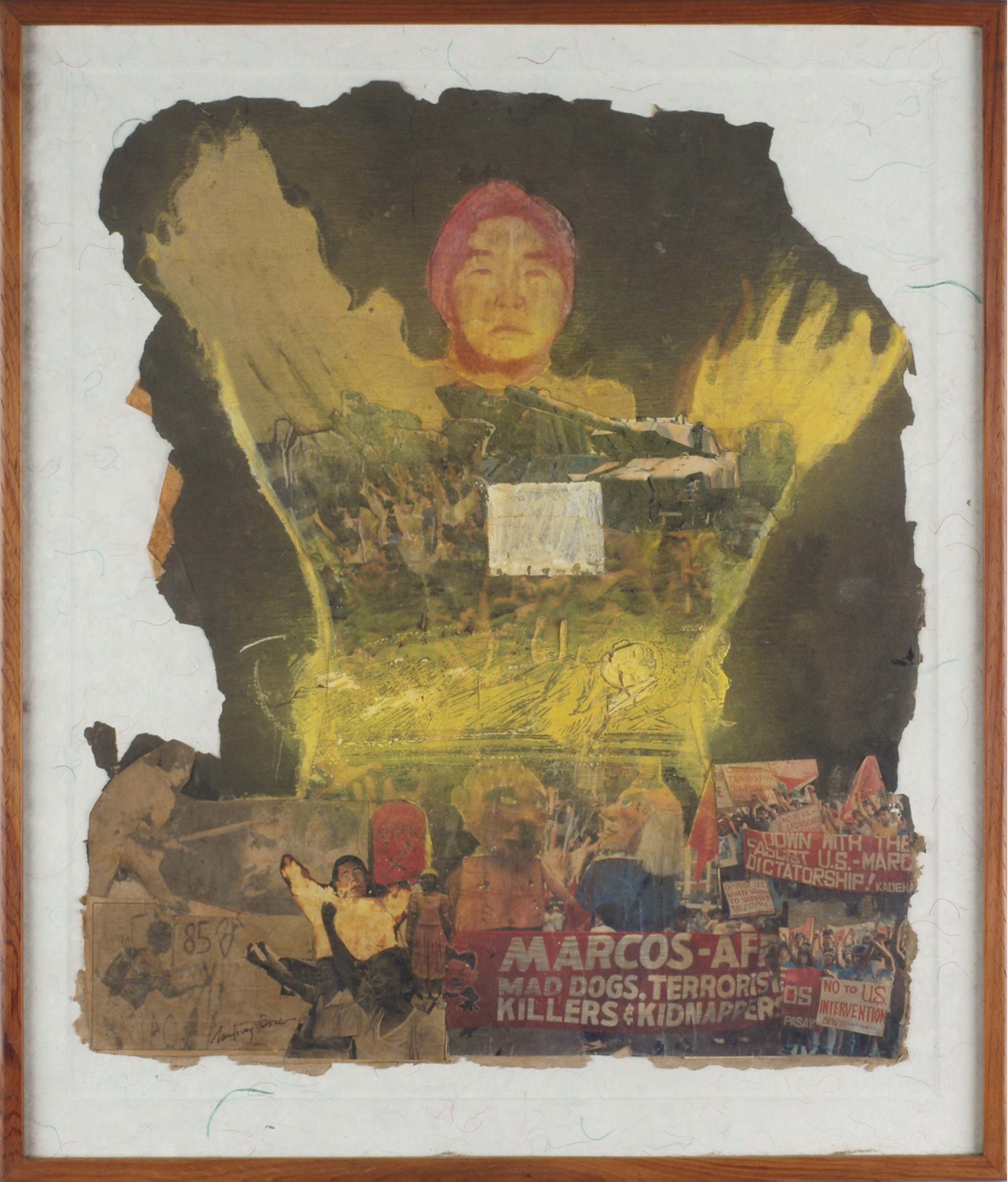

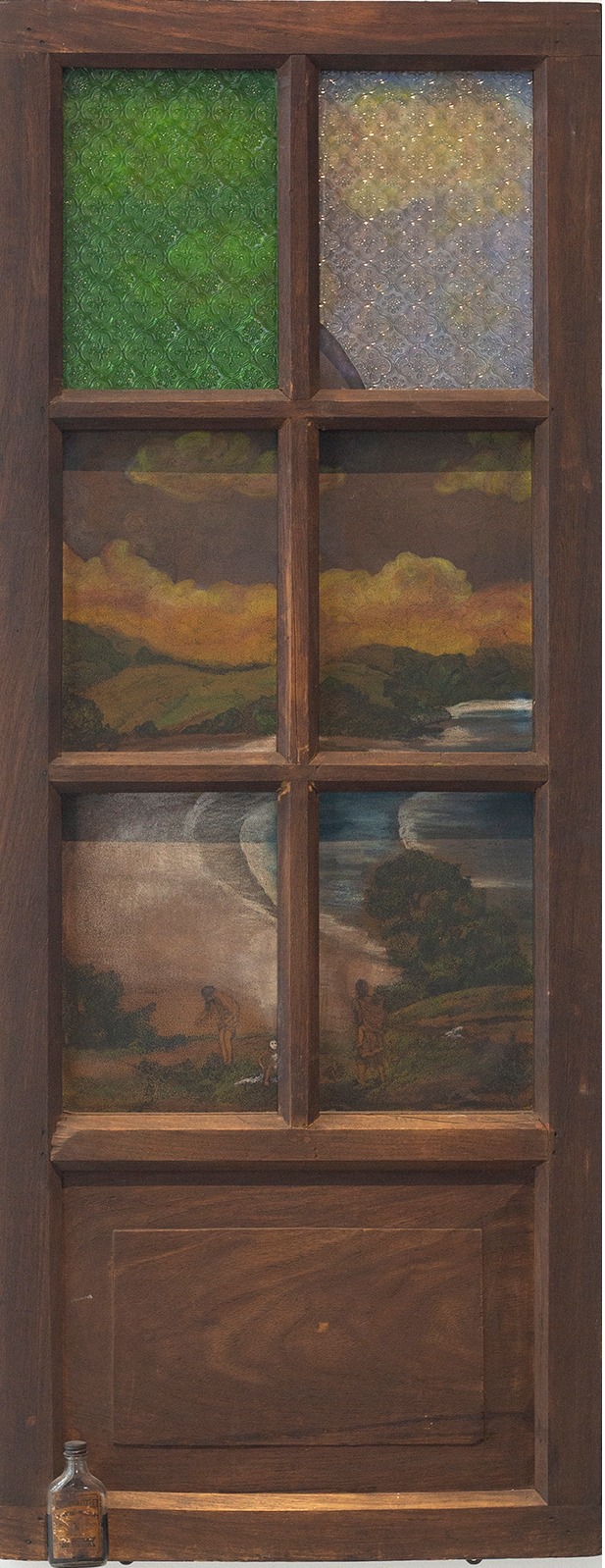

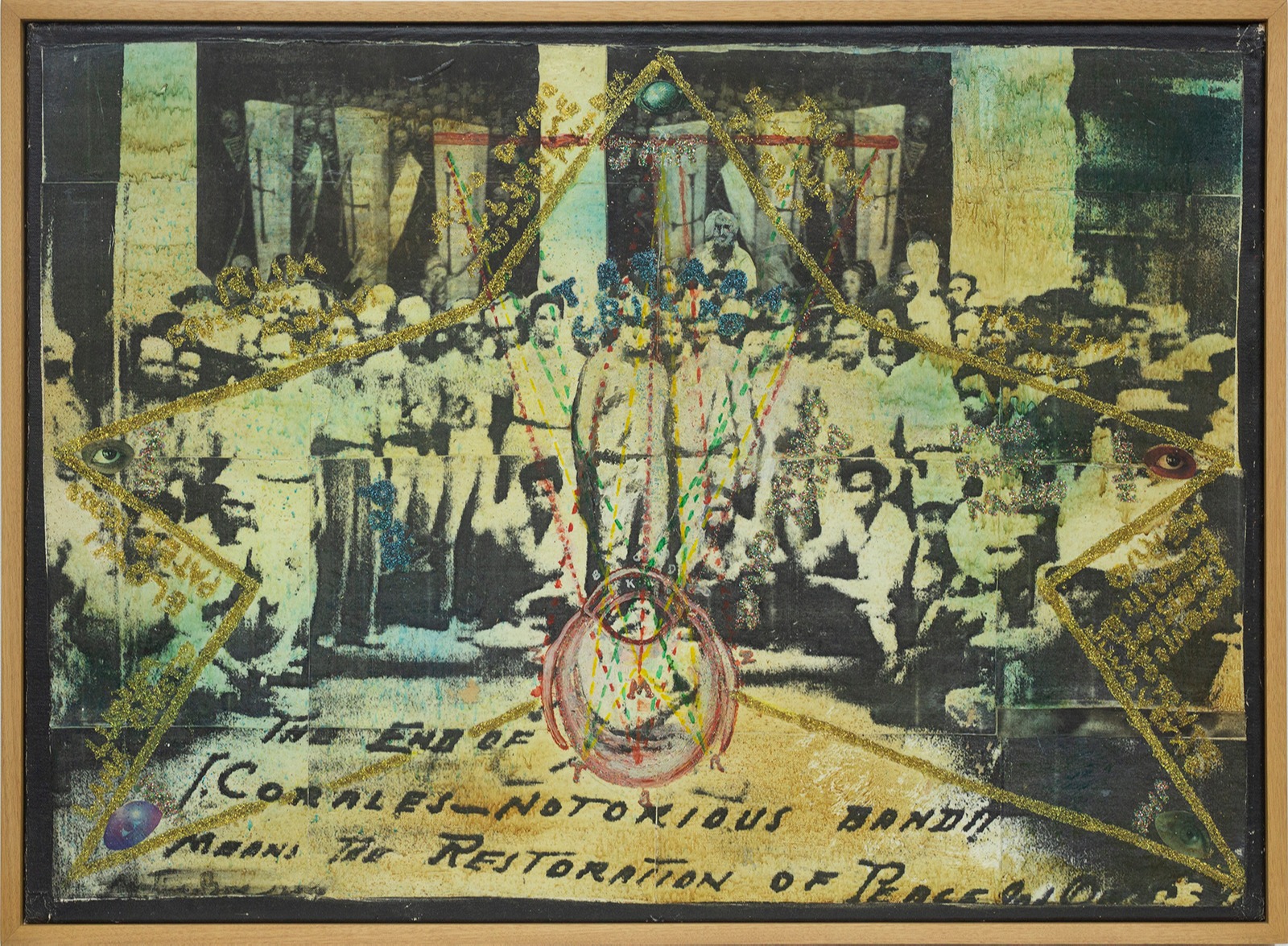

SILVERLENS is pleased to present Striking Affinities, a solo exhibition by Santiago Bose. This show, curated by Patrick Flores, marks the second cycle of the three-part exhibition series planned for the late artist entitled Santiago Bose: Painter, Magician; the first instalment, Bare Necessities occurred in 2019. All spaces within the gallery will be dedicated to this presentation, which features a myriad of works that reflect Bose’s artistic influences from a lifetime of travel and creative experimentation.

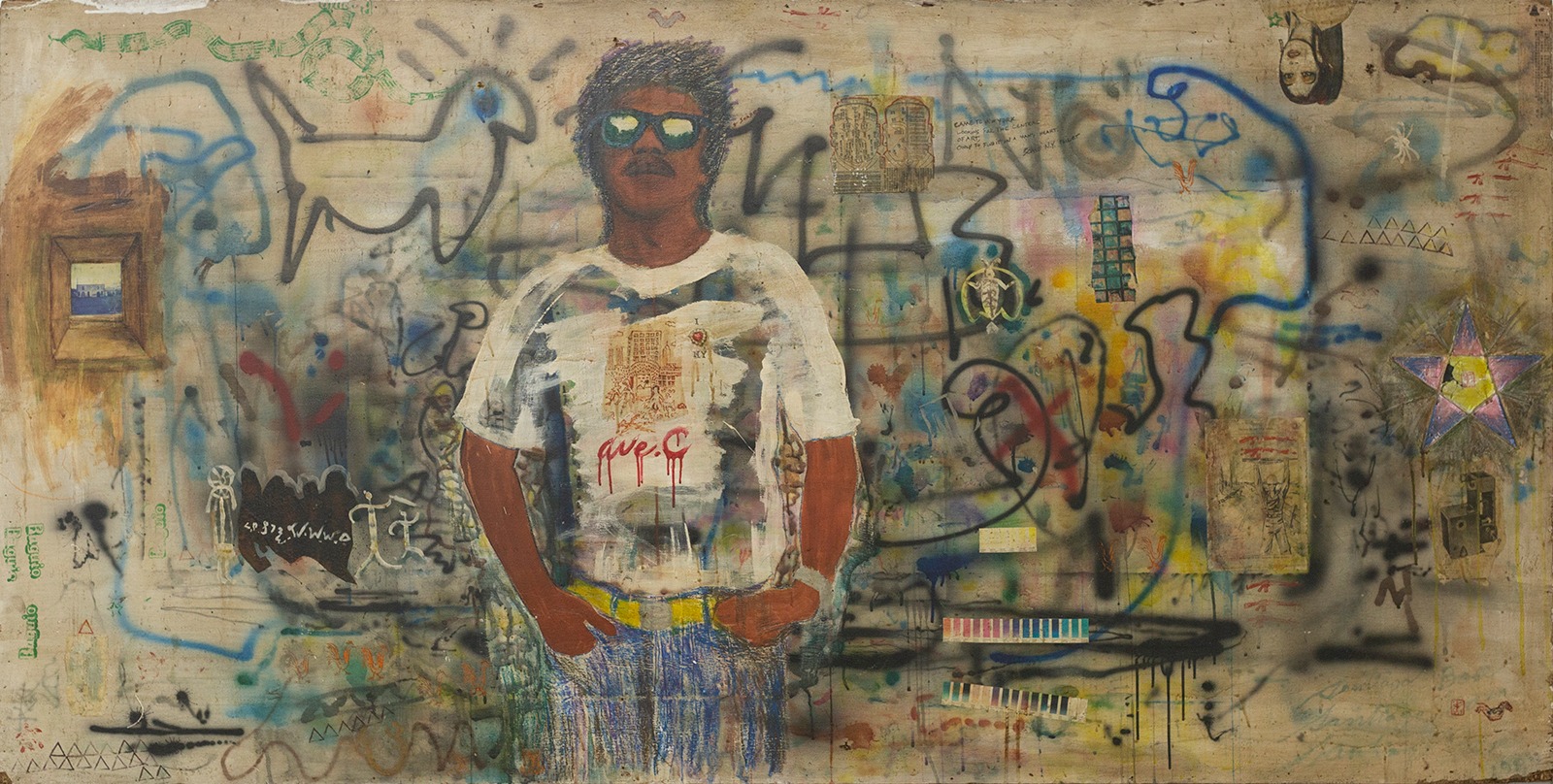

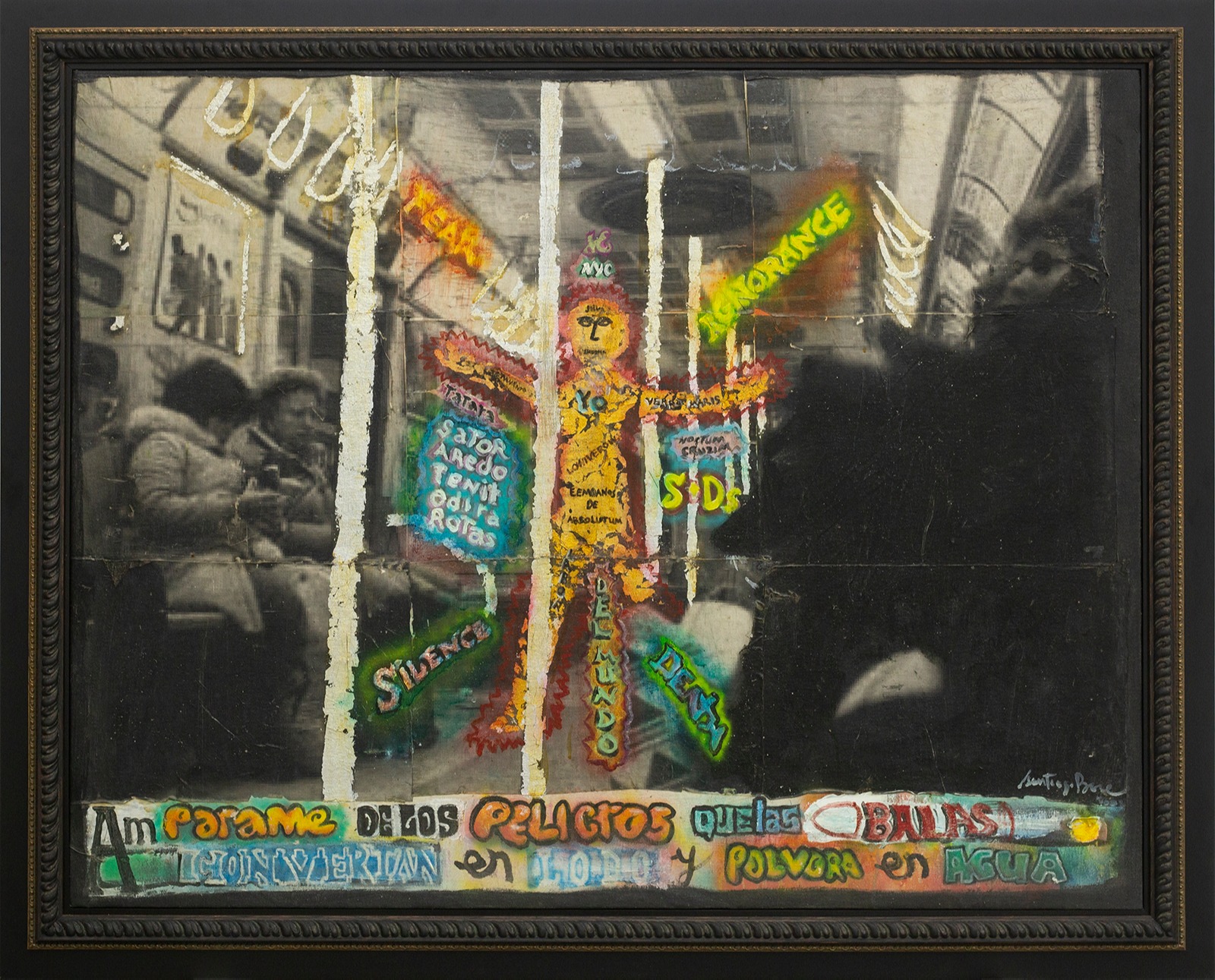

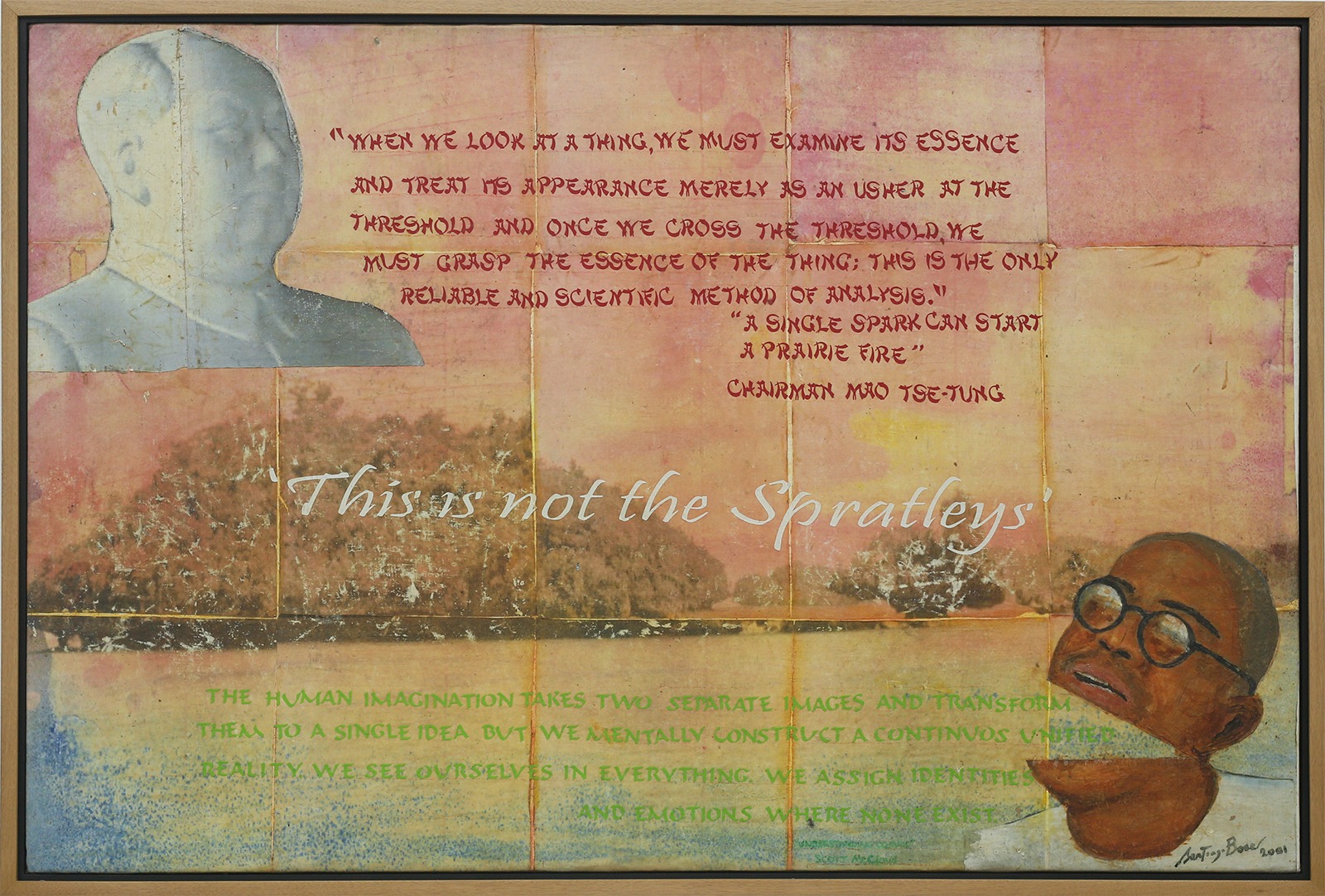

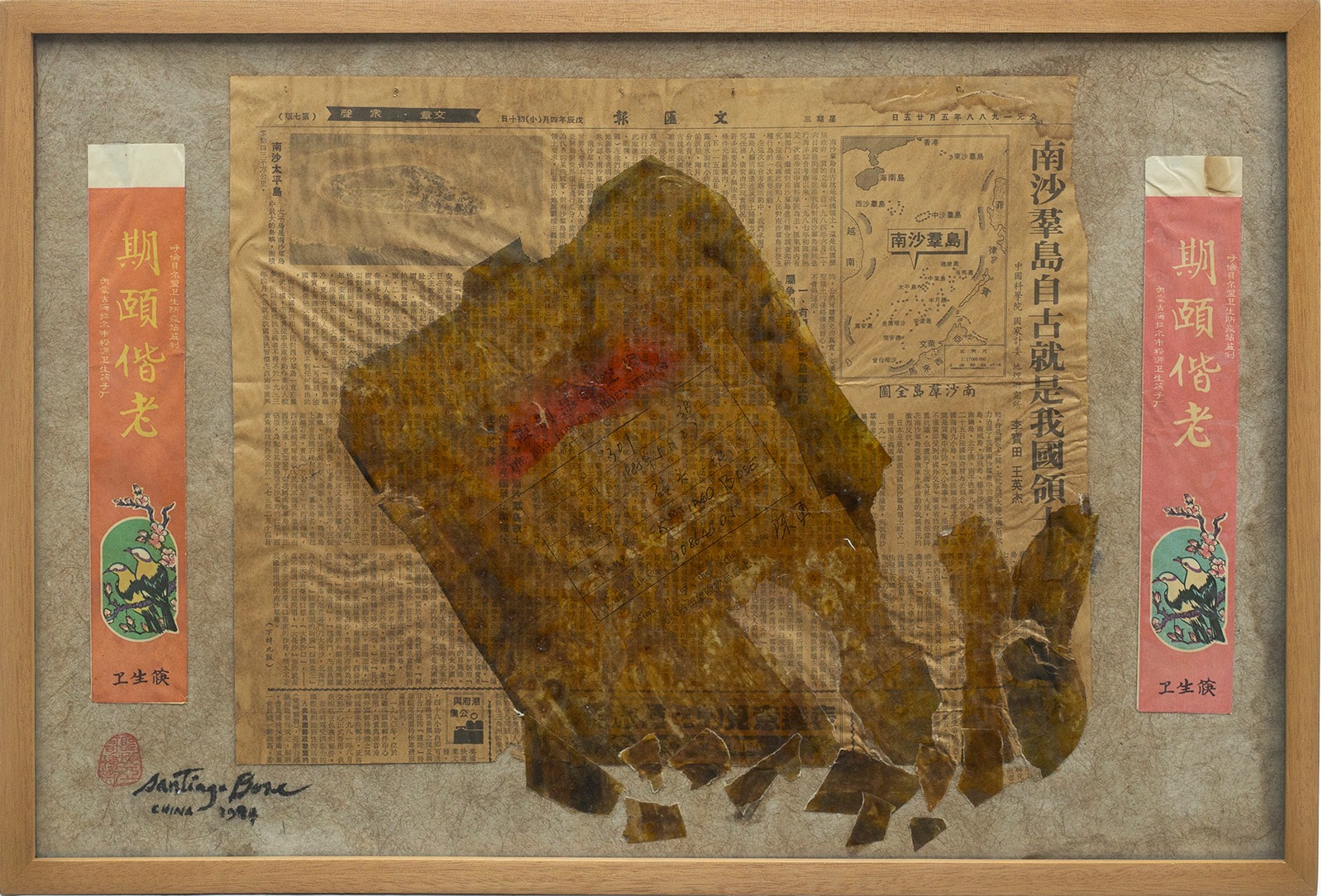

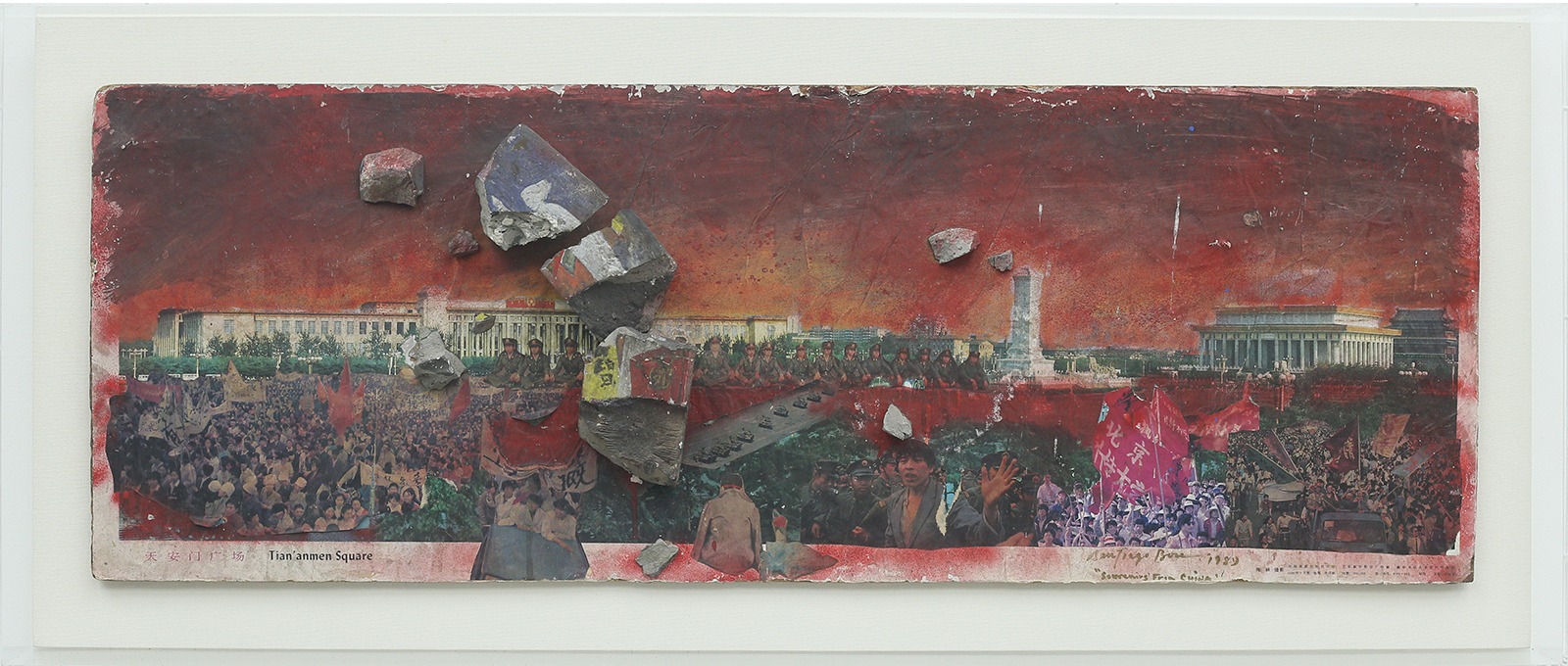

The exhibition explores the geographic coordinates of Santiago Bose’s practice: Baguio, Manila, New York, Adelaide, Bali, and Spratly Islands. These places are homelands, contact zones, passage ways, hot spots, exhibition sites – shaping the work of Bose in the same way that the artist in a reciprocal gesture shaped them. They are mapped out in the exhibition to remember the movements of Bose as well as to understand how he likewise speculated on possible worlds beyond the existing cartography within which he circulated with interest, if not with alacrity. Part of the three-part Bose project, this second iteration follows through Bare Necessities, which laid out the groundwork of artistic impulse and the fundamentals of risk.

Words by Patrick Flores.

The exhibition explores the geographic coordinates of Santiago Bose’s practice: Baguio, Manila, New York, Adelaide, Bali, and Spratly Islands. These places are homelands, contact zones, passage ways, exhibition sites — shaping the work of Bose in the same way that the artist in a reciprocal gesture shaped them. They are mapped out in the exhibition to remember the movements of Bose as well as to understand how he likewise speculated on possible worlds beyond the existing cartography within which he circulated with interest, if not with alacrity. Part of the three-part Bose project, this second iteration follows through Bare Necessities, which laid out the groundwork of artistic impulse and the fundamentals of risk.

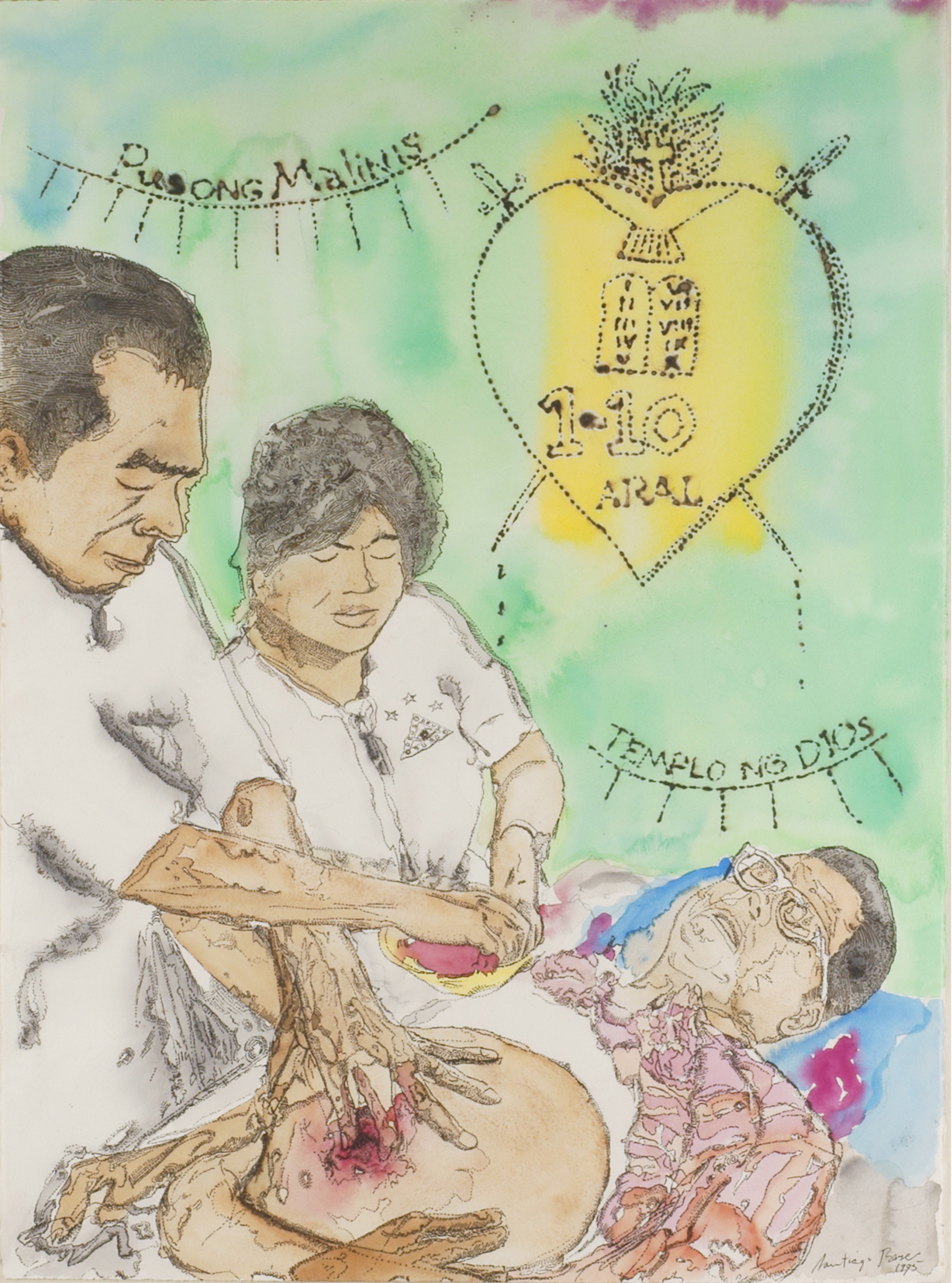

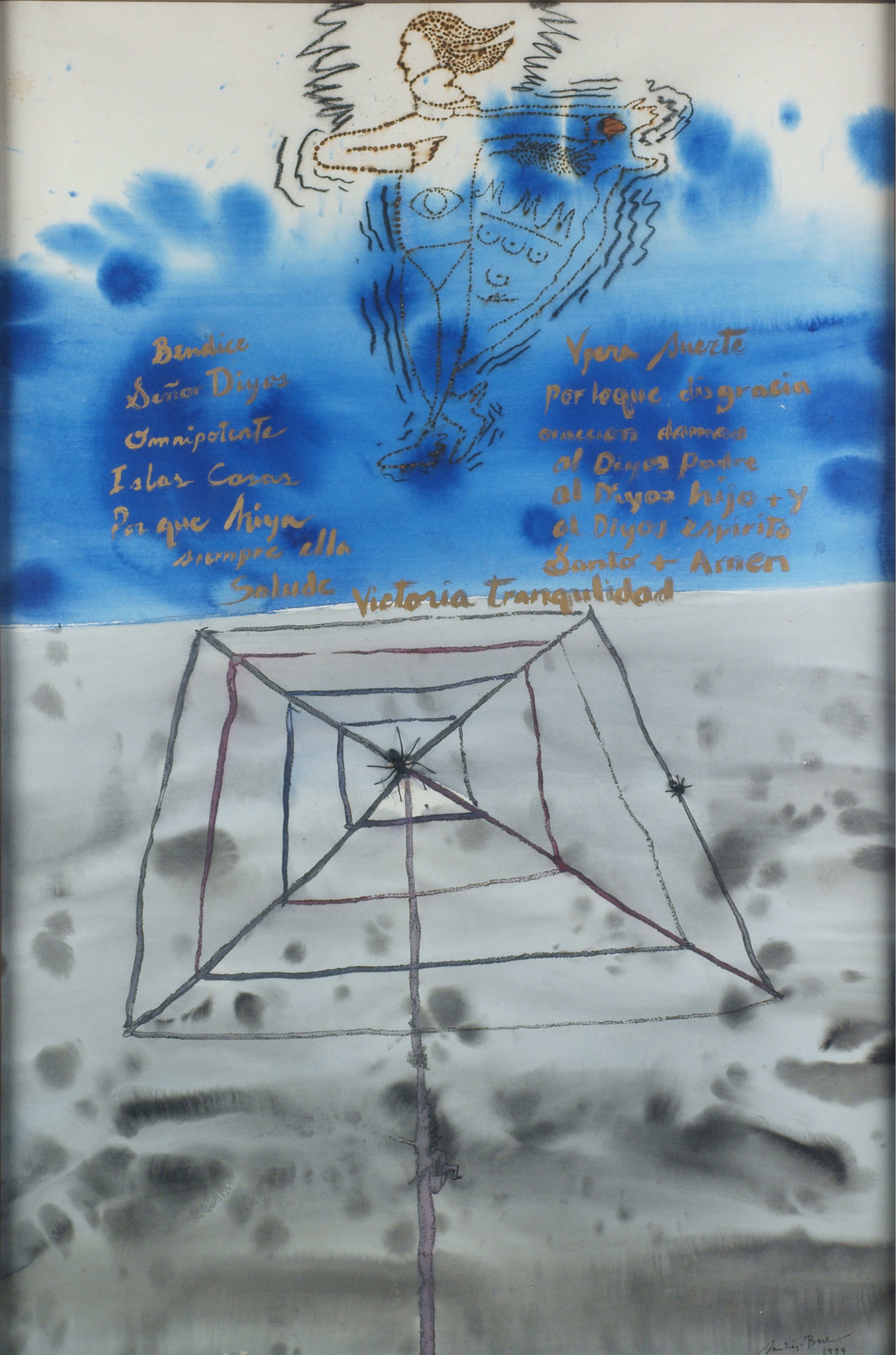

The term “striking affinities” flips the phrase “striking distance” to allude to how Bose has travelled extensively and reached out to peers for collaboration, solidarity, and discursive and political possibilities. The distance, in other words, would be crossed through various forms of engagement; and Bose does it strikingly, leaving marks in the places through which he passed and in the works made through and with those places. The word “strike” is vital here as it signals the urgency of a situation as well as the opportunity taken by the artist to make things happen in transitional space, reminding us of another phrase “strike anywhere” and the storied meaning of “strike” in protest and revolutionary movements. That being said, Bose has also stood his ground in the matrix of locations that has enabled him to sharply facet the global scene with an edgy perspective, or a perspective on or from the edge. This is evident in how his hometown Baguio yields a critical mass of images pertaining to kin, childhood, visual culture, and everyday folklore. Manila was for Bose an intersection, specifically at the University of the Philippines where he would be exposed to intellectual ferment and the means to effect social change. It can be speculated that notions of the “national consciousness” or “Philippine identity” may have taken root in Manila in relation to experience in and memory of Baguio but inflected by the cultural politics in the city. The anting-anting trope could well be a condensation of interests speaking to the need for an index of the “national” without diminishing the “local.” In fact this cipher of the national absorbs the local into its potent Filipino assertion of subjectivity. The fascinating meshing of the folk and the colonial in the talisman and its place in revolutionary history informs a potential nationalist metabolism.

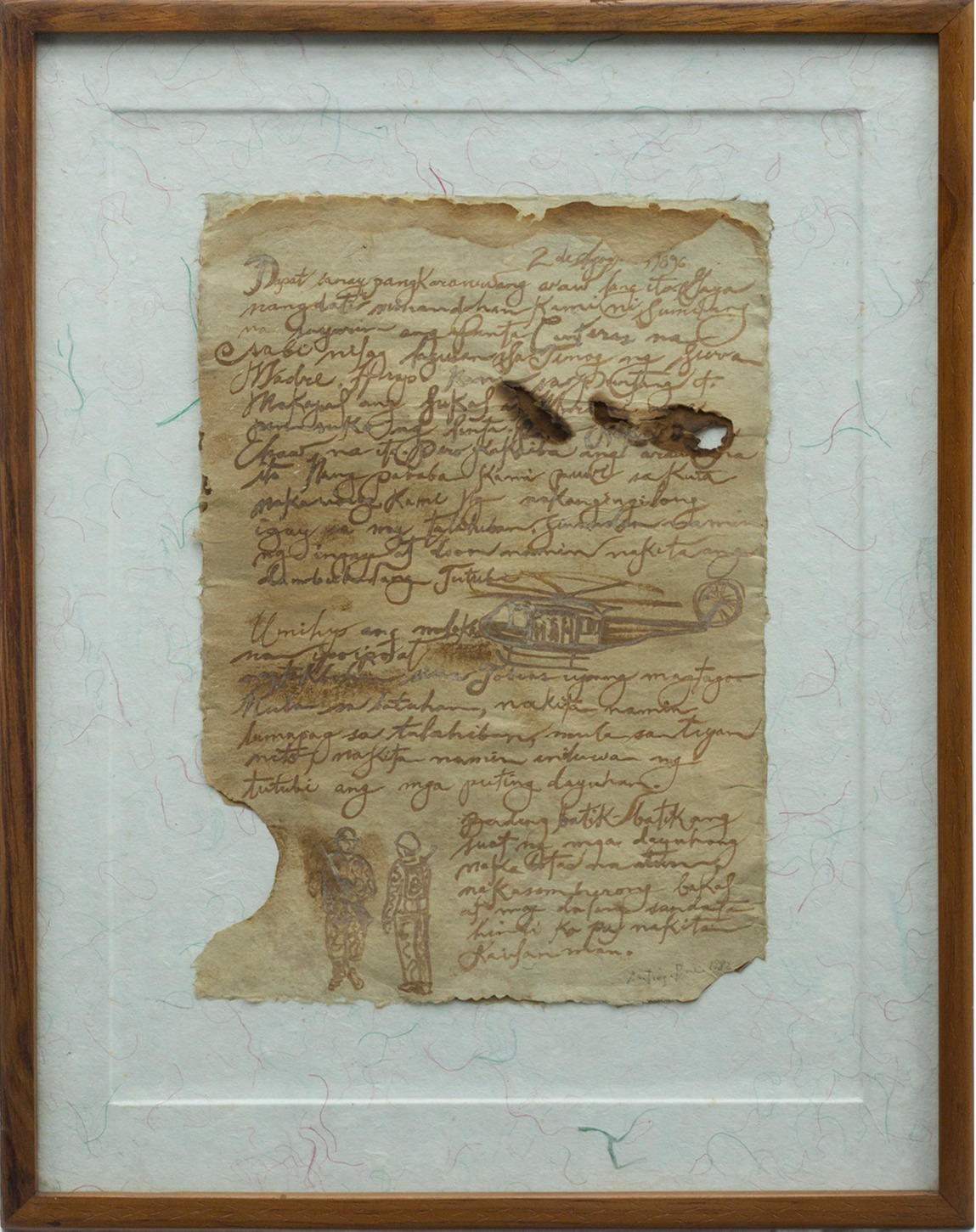

Bali was kind of a sojourn, a trip taken when he was in Jogjakarta, Indonesia in 1997 for the ASEAN Creative Interactions project. But it was interesting for Bose to produce works on paper using the method of boring fascinating holes into the paper from the sun’s rays, with the marks becoming pattern and then figure. If the Hindu Bali is imagined as typically prone to exoticism as well as a contrast to the Islamic and Javanese dominance, his Baguio may well be an equivalent site, owing to the sediments of American colonization and the wellspring of indigenous resistance. Just like the contact zone of Bali, Baguio was in itself at the conjuncture of the colonial hill station and the Cordillera. Like Bali, it attracts a large volume of tourists because of its cool weather, a respite from the oftentimes hideous heat of the metropolis. Underlying both Baguio and Bali is the discourse of the exotic and how the native, the hybrid, and the cosmopolitan reshape this fetish of the other, the mixture, and the worldly.

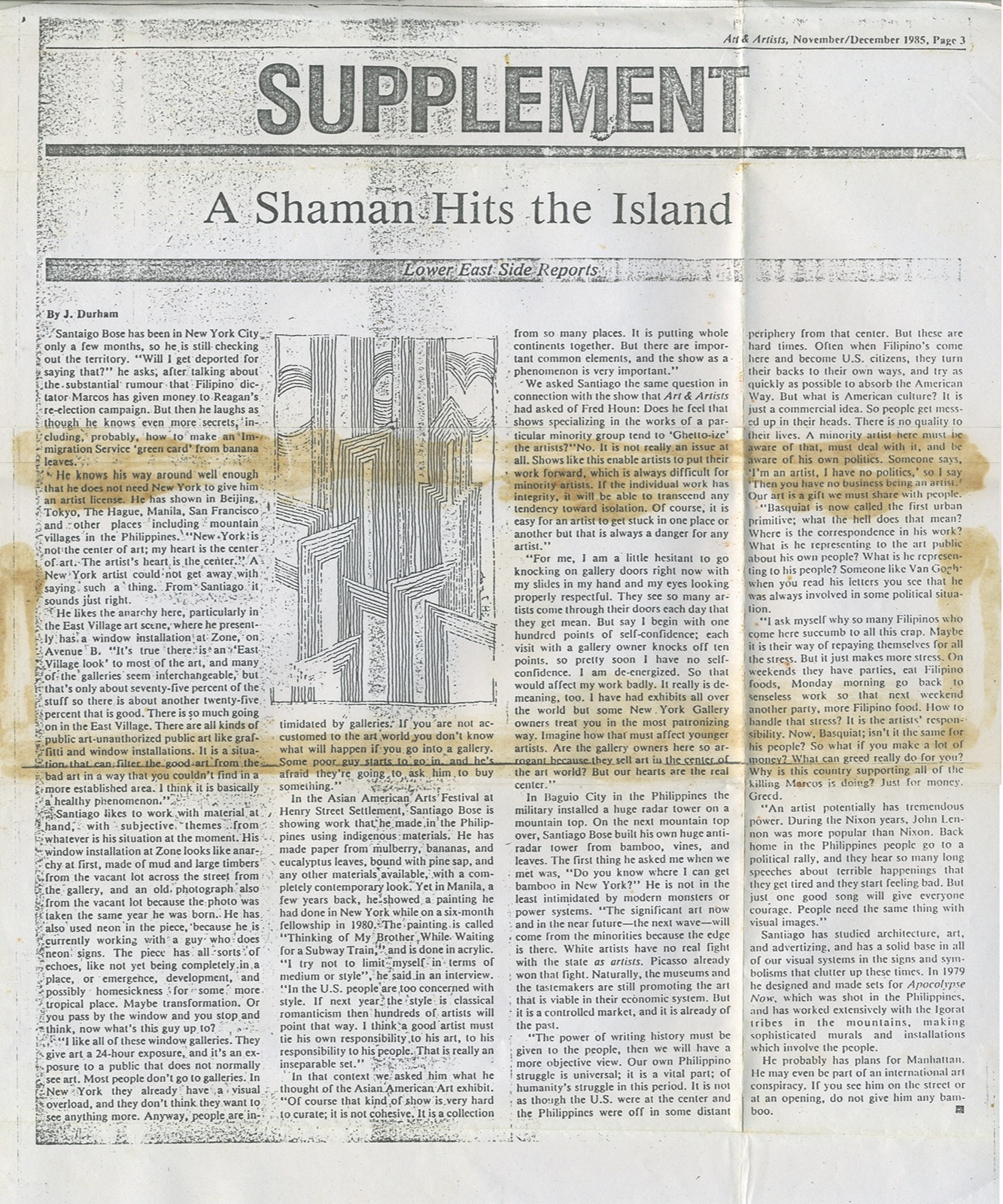

New York bore traces of the west, the center. But Bose chose to mingle at the margins, alongside practitioners who for years had been struggling with systemic discriminations against their persons and against their art. The artist Jimmie Durham wrote a text on Bose in 1985, casting him as a “shaman” who “hits the island.” Durham ends nearly facetiously: “He probably has plans for Manhattan. He may even be part of an international art conspiracy. If you see him on the streets or at an opening, do not give him bamboo.”

The time Bose spent in Adelaide to do installations for an art festival generated a suite of three installations and a walk, a remarkable achievement for a singular event. The title of the installations was emblematic of Bose’s striking affinities across terrains, Imagined Enclaves, Ephemeral Borders. His idea of borders and enclaves as imagined and ephemeral has over time prompted him to poach, breach, coalesce, trespass, settle, and span. Alison Carroll describes Bose’s work in Adelaide as constituting “points of cultural positioning” and his perambulation as a form of “painting his footprints...marking his trail.”

Finally, Spratly Islands is the speculative locus. It is a disputed territory with several claimants. The waters around lead to nation-state formations that pursue the rights to possess the domain. The hegemony of China over it reveals Bose’s relationship with the Great Tradition as well as the Superpower.

The approach of this exhibition is to assemble the different ways by which Bose has over time translated his movements across places in a gamut of expressions, from drawing to prints and on to intermedia works. The so-called ephemera that are so central in the production of the work find equivalent footing in the exhibition, sited alongside the more fully formed art work. But the exhibition is interested similarly in the work of art, and not only in the art work. What does art do and how does it do its thing? These questions are inscribed or enfolded into the question of significance: The work of art matters because it materializes within conditions. And so, here presented in the gallery are the hints of how the thing comes to be: sketches from the archives, documentation of exhibitions, visual diaries, criticism, and so on. To this end it can be argued that the striking affinity does not only pertain to cartographies but also to the creative and critical formation of the at once intimate and extensive work of art.

Words by Patrick Flores

Santiago Bose (July 25, 1949 – December 3, 2002, Baguio City, Philippines) was a mixed-media artist from the Philippines. Bose co-founded the Baguio Arts Guild, and was also an educator, community organizer and art theorist.

Bose often used indigenous media in his work, ranging from bamboo and volcanic ash, to the cast-offs and debris (found objects, bottles, “trash”). His assemblages communicated a strong sense of folk consciousness and religiosity, and the strength of traditional cultures in a culture inundated with foreign cultural influences.

Bose worked toward raising an awareness of cultural concerns in the Philippines. After studying at the College of Fine Arts at the University of the Philippines between 1967 and 1972, Bose continued his studies in the United States, at the West 17th Print Workshop in New York.

He returned to Baguio in 1986 and began his explorations into the effects of colonialism on the Philippine national identity. In particular, Bose focused on the resilience of indigenous cultures, like that of his home region of the Cordilleras.

Bose was the founding president of the Baguio Arts Guild in 1987. He became president again in 1992. The Guild is an active cultural association in the northern Cordillera region, emphasising regional tribal traditions and the importance of using indigenous materials. Bose played a formative role in establishing the Baguio International Arts Festival.

Through his work, Bose addressed difficult social and political concerns in the Philippines. His subject(s) were approached with deep criticality and gravity, although never without a sense of humor and wit, however irreverent.

Bose said, “…The artist cannot but be affected by his society. It is hard to ignore the pressing needs of the nation while making art that serves the nation’s elite… We struggled to change society, which is difficult and dangerous, and we also sought to preserve communal aspects of life. I too am haunted by visions of hardship, poverty, disenfranchisement of the ‘primitive’ tribes, but between outbursts of violence and exploitation are also tenderness, selflessness and a sense of community. These will always remain unspoken and unrecognized unless we make art or music that will help to transform society. The artist takes a stand through the practice of creating art. The artist articulates the Filipino subconscious so that we may be able to show a true picture of ourselves and our world.”

Bose was granted the Thirteen Artists Award by the Cultural Center of the Philippines in 1976. He has exhibited in major international events such as the Third Asian Art Show in Fukuoka, Japan and the Havana Biennial held in Cuba, both in 1989. In 1993, he was invited to the First Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art held at the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane, Australia. In 2000 Bose’s work was included in the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco’s exhibition “At Home & Abroad, 20 Contemporary Filipino Artists.” In June 2002, he was presented the “Gawad ng Maynila: Patnubay ng Sining at Makabagong Pamamaraan” (Cultural Award for New Media presented to outstanding Filipino Artist) by the City of Manila. In 2006, he was posthumously shortlisted for the National Artist award.

As a widely sought after artist for public commissions and artist residencies, Bose’s practice included extensive international travel and included several prominent grants and fellowships.

Bose’s work was marked by a conscious avoidance of a single recognizable style, by varied foreign and local influences, and by an experimental bent.

Patrick Flores is Professor of Art Studies at the Department of Art Studies at the University of the Philippines, which he chaired from 1997 to 2003, and Curator of the Vargas Museum in Manila. He is the Director of the Philippine Contemporary Art Network. He was one of the curators of Under Construction: New Dimensions in Asian Art in 2000 and the Gwangju Biennale (Position Papers) in 2008. He was a Visiting Fellow at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. in 1999 and an Asian Public Intellectuals Fellow in 2004. Among his publications are Painting History: Revisions in Philippine Colonial Art (1999); Remarkable Collection: Art, History, and the National Museum (2006); and Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia (2008). He was a grantee of the Asian Cultural Council (2010). He co-edited the Southeast Asian issue with Joan Kee for Third Text (2011). He convened in 2013 on behalf of the Clark Institute and the Department of Art Studies of the University of the Philippines the conference Histories of Art History in Southeast Asia in Manila. He was a Guest Scholar of the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles in 2014. He curated an exhibition of contemporary art from Southeast Asia and Southeast Europe titled South by Southeast and the Philippine Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2015. He was the Artistic Director of Singapore Biennale 2019 and is the Curator of the Taiwan Pavilion for Venice Biennale in 2022.

Installation Views

Baguio

New York

Spratly Islands

Manila

Adelaide