Frieze Los Angeles

Stephanie Syjuco & Jenifer K Wofford

Booth 15, Santa Monica Airport

About

They couldn’t be more different from each other. And they couldn’t be closer to each other.

In traveling the few steps between these two artists’ works on exhibition together at Frieze Los Angeles, we embark on a journey of intimate dissonance between Stephanie Syjuco’s black and white archival photographs and Jenifer Wofford’s birthday confetti colored paintings.

We pace back and forth between what Syjuco calls the “volume of things” and what Wofford calls the “in-betweenness of things.”

If the juxtaposition of stark opposites yields the pleasures of rupture, it also yields the pleasure of detecting deep continuity.

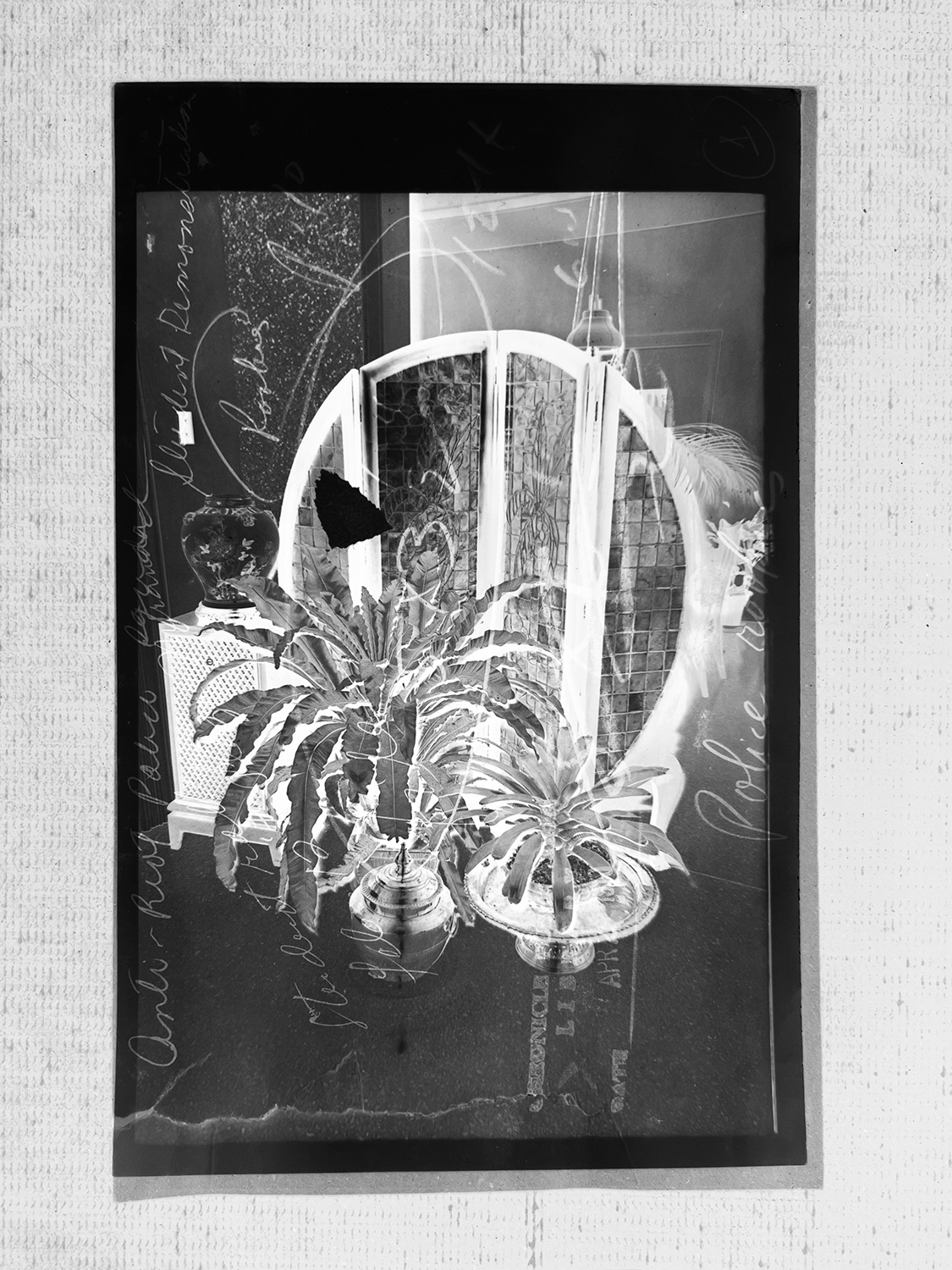

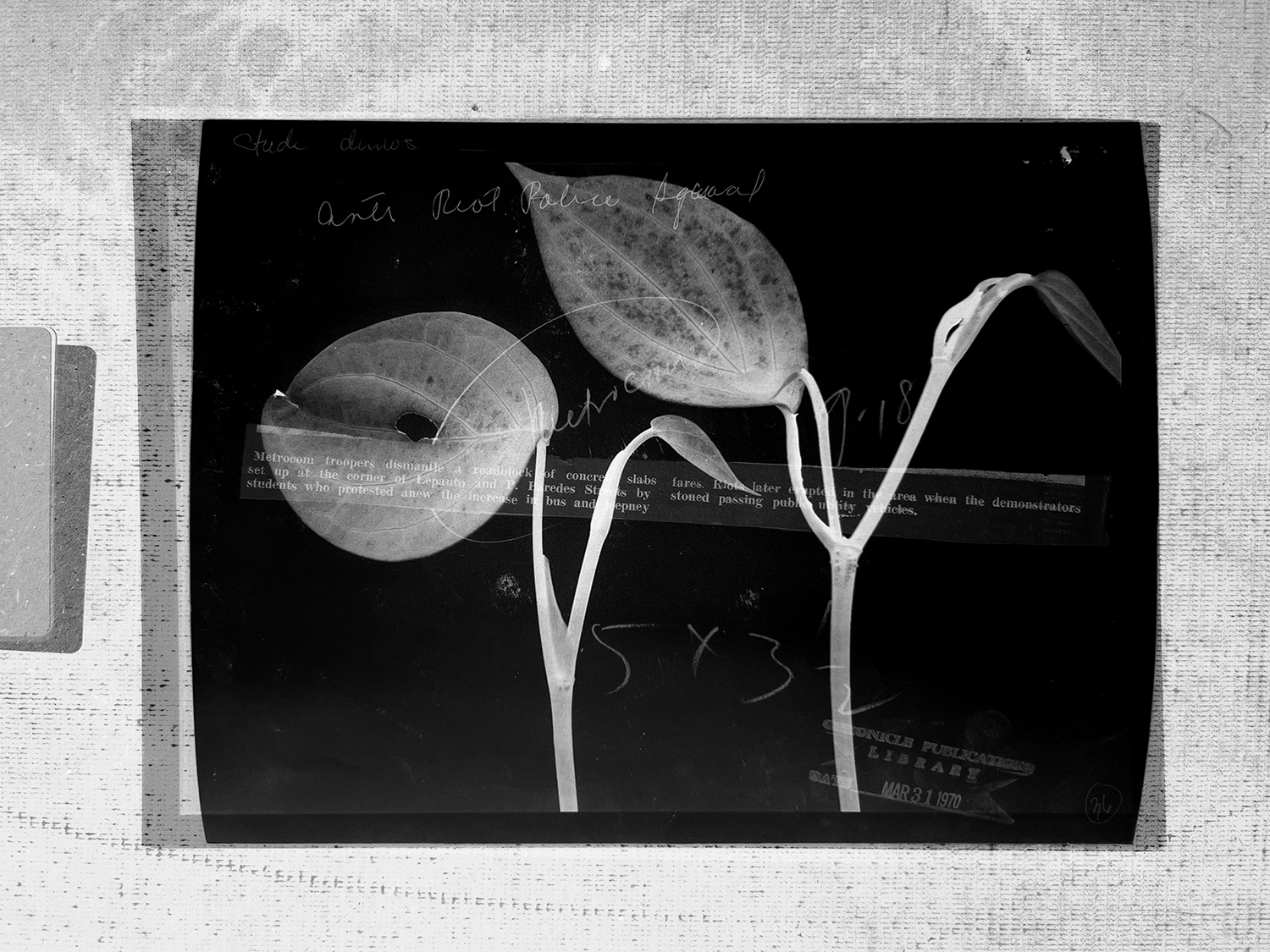

We delight in these visual artists’ commitment to conceptual puns and word play. Syjuco’s staged archival photographs of 1960s-1970s Philippines are all about turning the volume – the noise -- of things up or down, which she achieves by making the volume – the quantity – of amassed photos bigger or smaller. Wofford’s Comfort Room paintings series bring bright-colored whimsy to threshold spaces like the hospital room, the motel room, and the “C.R.,” the Filipino shorthand euphemism for the American restroom or the British water closet. Wofford’s signature deployment of color comic aesthetic is preceded by her extensive work on the sterile white uniform of the nurse.

We thus are invited to reckon with the coupling of two iconic female figures of the Philippines: Imelda Marcos and the nurse. Even those who know next to nothing about the Southeast Asian country and former American colony easily can conjure images of Marcos’ bouffant hairdo. And if one ever has visited a hospital in the global North, there’s a pretty good chance that one has been treated by a migrant Filipina nurse, even without knowing much about the Philippines’ decades-long policy of acting as a labor-brokerage state that exports its workforce around the world in exchange for remittances.

The Volume of Things

Up until recently, Syjuco’s interest in the archive has focused on American archives like the Smithsonian and she now has moved to the Filipino archive. In Manila, Philippines, Syjuco conducted research on the newspaper Manila Chronicle, active from 1945-1972, a period that spanned the end of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, decolonization from the United States, and Ferdinand Marcos’ declaration of martial law. The newspaper collection consists of thousands of photographs taken by Filipino photojournalists in the newly independent republic and used to print the news.

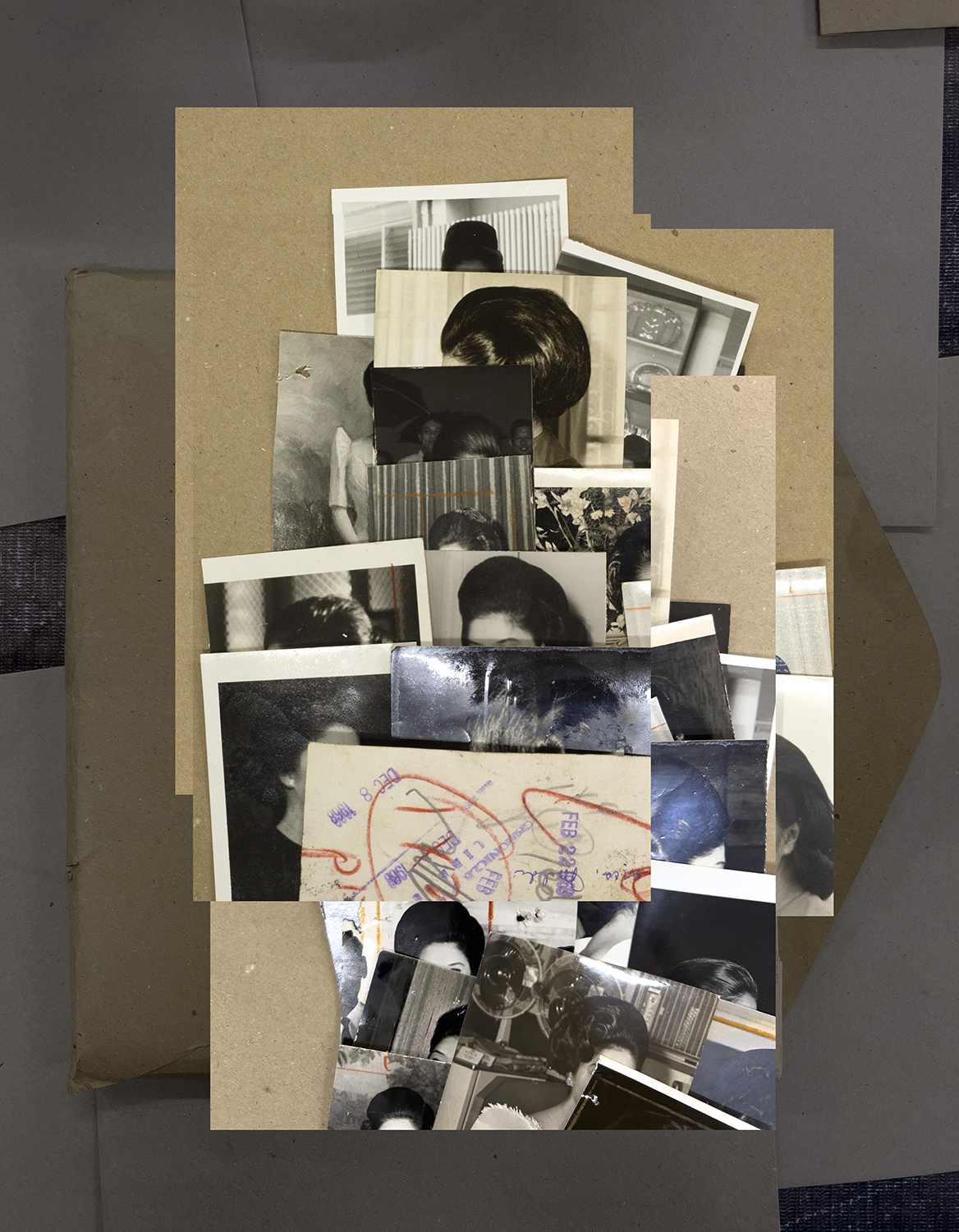

Since none of the images have been digitized, the artist’s task was haptically labor-intensive as she touched, selected, arranged, and shot her own photographs from above. The artist’s digits – her fingers – are all over the images.

Syjuco’s staging of archival photographs has the effect of turning the volume of things up or down. Ear-splittingly loud photographs of riot police and anti-dictatorship protestors live alongside, atop, and beneath photographs of upper-middle class Filipinos’ embrace of quiet elegance, effortlessly mod fashion, and easy consumption.

Syjuco is known for her technique of cropping out details from photographs and films, especially central figures and the main action. In one of the montages, Imelda Marcos’ face is cropped out but the bouffant hairdo of the dictator’s wife is unmistakable. In another montage, all we see are Ferdinand Marcos’ hands, which themselves are marked by the fingerprints of an artist who touches and handles a history of authoritarianism and liberatory struggle now on the brink of amnesia in the current post-Duterte, Marcos, Jr, era.

In her earlier work, well before editing software was available, Syjuco manhandled mainstream Hollywood films about the Vietnam War that were shot in the Philippines like Apocalpyse Now and Full Metal Jacket. Syjuco painstakingly blacked out all images except the Philippine landscape, and so the soundscape of war – helicopters, rock-and-roll music, explosions, screams – becomes even eerier because it’s juxtaposed with large swaths of black screen occasionally interrupted by the gentle flickering appearance of tranquil images of tropical skies, foliage and beaches. When Syjuco crops things out, there is an appeal to other senses. When the volume is turned down, we can pay attention to things that otherwise are crowded out. Trampled on. And yet live on.

The In-Betweenness of Things

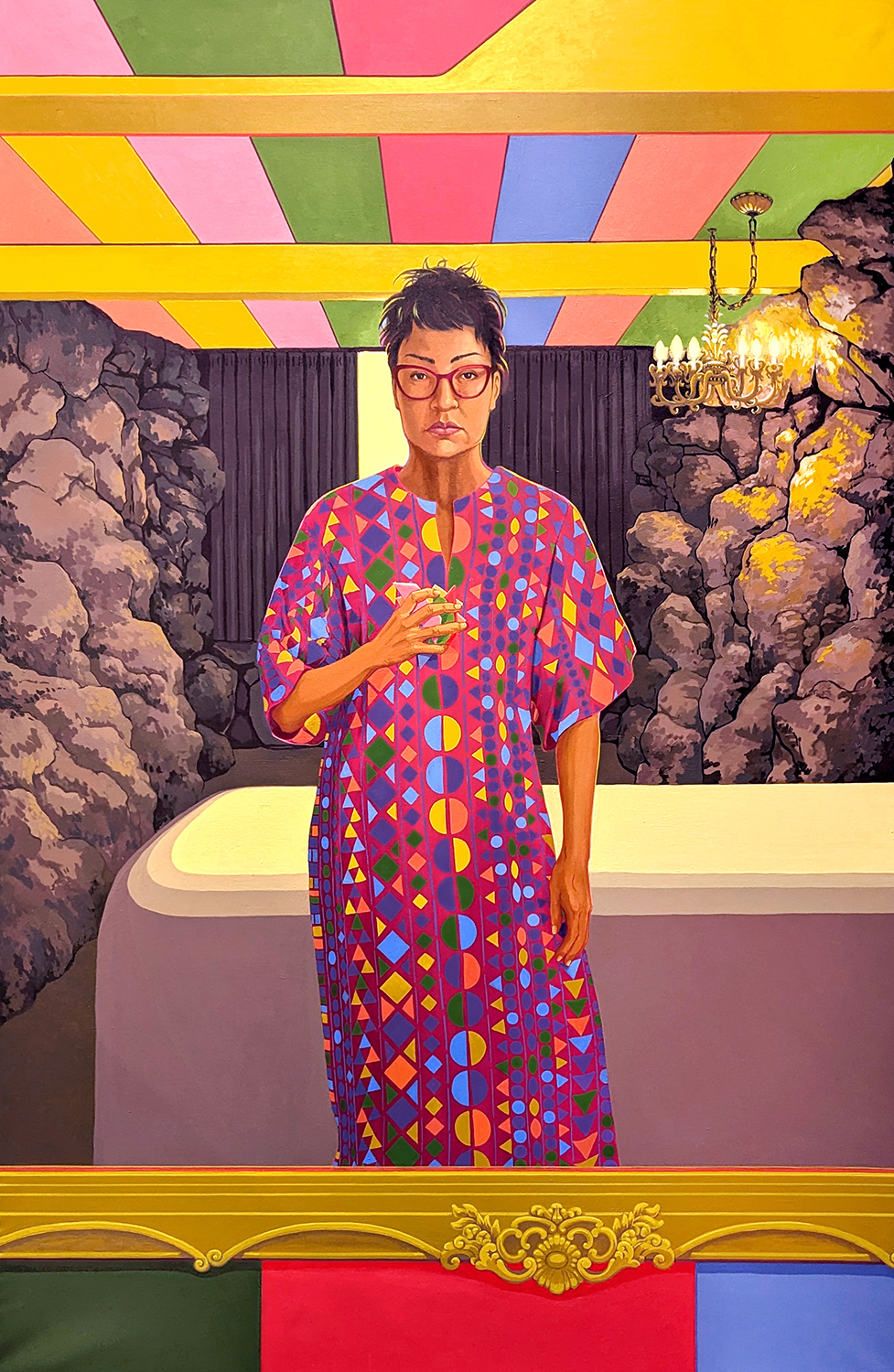

Wofford’s Comfort Room paintings series is a carnival parade of color comic aesthetics and whimsy that nonetheless is tinged with a lonely grief. She bedazzles sterile spaces like the hospital room, the motel room, and the bathroom, which are associated with a series of mutually intertwined oppositions -- hygiene and filth, healing and sickness, and privacy and exposure.

The word “toilet” comes from the mid-16th century French word “toilette” for “cloth, wrapper.” Etymologically and functionally, the toilet refers simultaneously to washing, dressing, and grooming oneself; and to a receptacle, container or room for urination and defecation. The oppositions between care and repulsion and between clean and dirty are built into the space. So it’s no surprise that Wofford paints a portrait of the corner of a room, where two edges meet.

Attracted to “liminal spaces,” as she puts it, Wofford implicitly proposes an important alternative way to engage with works by biracial and multiracial artists of color, who understandably report weariness with and wariness of the reduction of their work to simplistic biography. Wofford creates a self-portrait – clad in a loose brightly colored smock that also resembles the outline of a hospital gown, the artist is making a selfie in front of a mirror – through the liminal space of the corner, which is characterized by the meeting of lines (rather than the liminal space of the threshold, which is characterized by the crossing of lines and boundaries). Along with the artists Gina Osterloh and Paul Pfeiffer, who also happen to be biracial Filipino Americans, Wofford is committed to the investigation of architectural corners, perspectival horizons, and the Cartesian grid as a way to interrogate how the figure gets entrapped.

Wofford cannily interweaves comedy and sorrow. The rocks, for Wofford, are “grief markers” and their grey stolidity do indeed threaten to break our hearts. At the same time, for anyone who saw the movie Everything Everywhere All at Once, Wofford’s rocks recall the film’s hilarious scenes of mother and daughter’s incessant squabbling portrayed as two boulders perched at the precipice of a canyon. Wofford’s rocks are looking at her paintings, wondering what to say, one of them with a blank speech bubble emoji.

For paintings that deliberately cultivate the static and the flat, there is so much depth. We just need to know where to look and how not to overlook.

– Sarita Echavez See

Stephanie Syjuco (b. 1974, Manila, Philippines; lives and works in Oakland, California) is known for her investigative, research-based practice encompassing photography, sculpture, and installation. Progressing from handmade and craft-inspired mediums to digital editing and archive excavations, her work employs open-source systems, shareware logic, and capital flows to scrutinize issues related to economies and empire. Initially exploring image-based processes and their implications in constructing racialized, exclusionary narratives of American history and citizenship, she has shifted her focus to the history-building and myth-making undertaken by Filipinos in their newfound independence. From critiquing images of American colonial anthropology in the Philippines, to investigating historical museum collections and shuttered newspaper archives, her projects attempt to reframe and “talk back” to the archive.

Syjuco received her MFA from Stanford University and BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including a 2014 Guggenheim Fellowship Award, a 2020 Tiffany Foundation Award, and a 2009 Joan Mitchell Painters and Sculptors Award. She was a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow at the National Museum of American History in Washington DC in 2019-20 and is featured in the acclaimed PBS documentary series Art21: Art in the Twenty-First Century. Her work has been exhibited widely, including at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art, The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Getty Museum, The Walker Art Center, and The 2015 Asian Art Biennial (Taiwan), among others. A long-time educator, she is an Associate Professor in Sculpture at the University of California, Berkeley.

Jenifer K Wofford (b. San Francisco, California; lives and works in San Francisco) is an artist and educator who creates work defined by hybridity, history, calamity and global culture informed by her upbringing as a Filipina-American raised in Hong Kong, the UAE, Malaysia, and California, as well as her experience as a longtime educator in a diverse range of communities. She is one third of the Filipina-American artist trio Mail Order Brides/M.O.B. Her interdisciplinary practice encompassing her intercultural education incorporates the intersections and overlaps of drawing, performance, video, web and print.

Wofford holds degrees from the San Francisco Art Institute (BFA) and UC Berkeley (MFA). Her work has been exhibited in the Bay Area at the Berkeley Art Museum, Oakland Museum of California, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Southern Exposure, and Kearny Street Workshop. Further afield, she has shown at New Image Art (Los Angeles), Wing Luke Museum (Seattle), DePaul Museum (Chicago), Manila Contemporary (Philippines), VWFA (Malaysia), and Osage Gallery (Hong Kong). Wofford’s awards include the Eureka Fellowship, the Murphy Fellowship, and grants from the Art Matters Foundation, the Center for Cultural Innovation, UCIRA, and the Pacific Rim Research Program. She has also been artist-in-residence at The Living Room, Philippines, Liguria Study Center, Italy and KinoKino, Norway. A well-known arts educator, she is faculty in Fine Arts and Philippine Studies at the University of San Francisco. She has also taught at Stanford, UC Berkeley, San Francisco Art Institute, California College of the Arts and San Francisco State University.

Installation views

Works