Galleon Trade

Carmen Argote, Patricia Perez Eustaquio, Jorge Rosano Gamboa, Patrick Martinez, Elaine Navas, Bernardo Pacquing, Carlos Villa, Jenifer K Wofford

Silverlens, New York

About

[…] And then the galleons want

to shop in the mall in the suburbs.

Everything they see there is like the secrets

They once carried in their holds.

Racks of blouses like sacks of gold, tiers of blenders

Like crates of silver. The food courts

Remind them of their full bellies before the trips home,

The weight in the center of the body

After it has eaten everything, the stomach glossy and pink

As a shopping bag. […]

—Rick Barot, "Galleons 8," The Galleons (Milkweed Editions, 2020)

The word hold bears many meanings. Among other nuances, when used as a verb, to hold can indicate possession or ownership; it can suggest physical restraint or temporal delay; and it can reference one’s perspective or judgment, one’s esteem or position. When used as a noun, the hold indicates storage space. Often related to transport, it references the cargo area of a plane or ship, and is usually interior, under and below the main cabin or decks. These multiple meanings recur across Rick Barot’s poetry collection, The Galleons, which leaps across centuries and continents to consider the enduring hold of the Manila galleon on contemporary life. Such ideas find visible form in the artworks presented in “Galleon Trade” at Silverlens New York. Featuring works by artists from the primary ports of call of this once-dominant global trade route, the exhibition offers a conceptual framework that draws on the historical and material legacies of the Manila Galleon, its ships and its goods, as well as the pervasive, if often invisible, lines of connection about memory and origins.

Starting in 1565 and lasting nearly two and a half centuries until 1815, the Manila Galleon encompassed an armada of ships controlled by the Spanish empire. As a precursor to today’s globalized economy, these vessels carried and deposited resources across a geographically vast network of exchange. However, the significance of the Manila Galleon extended beyond pure commerce: as a mechanism of wider geopolitical, colonial, and cultural structures, galleon trade not only prompted the circulation of goods, but also people, technology, customs and traditions. Hailing from the Philippines, Mexico, and California, the artists included in the exhibition represent the contemporary descendants of this inheritance.

This palimpsest history is manifest in the paintings of Patrick Martinez, whose Birds of a Feather, references connections across cultures, time, and material histories in its very title. A composite form, the wall-work combines the vernacular architecture and flora of Martinez’s natal Los Angeles with Filipino Machuca tile and iconography derived from ancient Mesoamerican mural paintings at Cacaxtla in Mexico. From this latter site, Martinez extracts the outline of a bird in neon, which in its original context, faced off with the Mayan god of merchants. A reference to the Indigenous trade routes that existed prior to the Spanish, Martinez’s sourcing of this imagery, in combination with his more contemporary references, extends the temporal parameters of galleon trade, fusing the deep past with the present, and encompassing wider indigenous and diasporic histories.

Jorge Rosano Gamboa and Patricia Perez Eustaquio similarly address the cultures present in the territories prior to galleon trade whose traditions later became absorbed by its commerce. Nenepilli – lengua de pacifico is a pedal-loom tapestry by Rosano, made in collaboration with master weaver José Mendoza. Like Martinez, Rosano looks to ancient Meso-American sources to develop his iconography. Here, he turns to the Zouche-Nuttall Codex to develop the curved forms which derive from symbolic representations for such elements as clouds, water, and blood, and are rendered as tongues. Dyed using indigo and cochineal, two luxury materials transported on the Manila Galleon, the work drapes in a sea of lingue that envelops the viewer within the watery environs of the galleon trade. Eustaquio also adopts the tapestry tradition in her Death of Magellan (After Amorsolo). This digitally woven work transfigures the canonical history painting by celebrated Philippine artist Fernando Amorsolo, which depicts the Spanish conquistador’s fatal attempt to circumnavigate the globe. Magellan’s failed voyage is considered a precursor to the route traversed by this Manila Galleon, and Eustaquio’s work invites us to reconsider the meaning of his death at the hands of the Indigenous peoples on island of Mactan.

Eustaquio’s tapestry is paired with her Fountain series, handwoven sculptures made from abacá, a prized fiber derived from a plant native to the Philippines used in tapestries as well as fine clothing. Playing with scale, Eustaquio weaves abacá to evoke the filigreed forms of native Philippine jewelry, exploded into grand proportions. In turning to indigenous ornamentation for information, the artist evokes another treasured material – gold – which, like abacá, circulated via the galleon trade routes. Indeed, the golden shimmer of the Fountain series is enhanced by Eustaquio’s use of gazing balls, whose mirrored surfaces invite the viewer to contemplate the past, present, and future of the intertwined histories activated in her work.

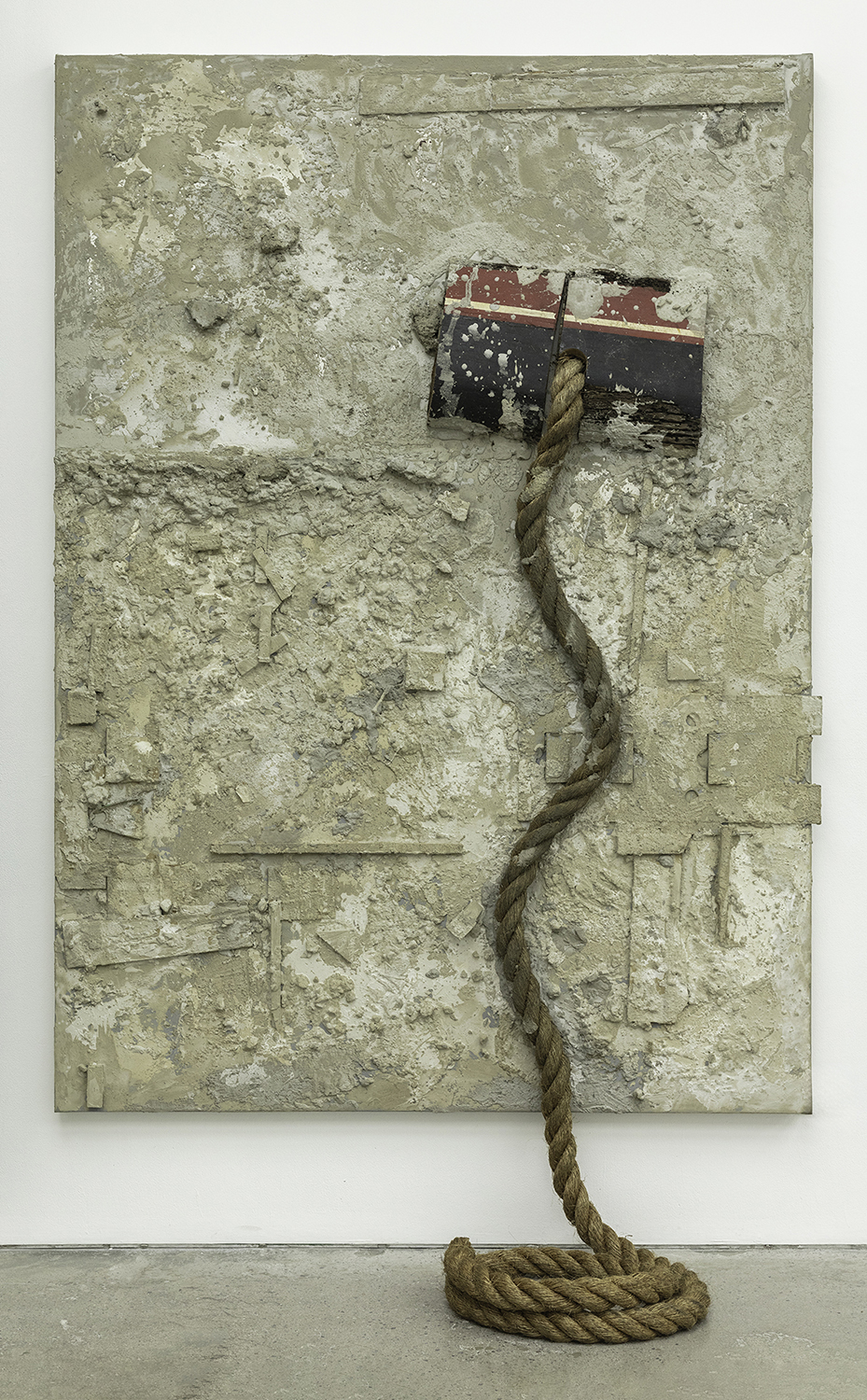

Also known as “Manila hemp,” abacá was not only valued as a commodity, but was also used to make rope and shipping cordage, essential for both Indigenous and colonial vessels of trade. At Silverlens, this connotation allows for Eustaquio’s sculpture to be read in relation to rigging or anchorage. It also invites relations between other works in the show which incorporate rope and binding, including Carmen Argote’s jackets for mom/Domestic Familial and Bernardo Pacquing’s assemblage Stowaway. Pacquing’s piece is created from urban debris salvaged in Manila, such as a found rope and a wooden rat guard, used on ships to prevent unwanted stowaways. Attached to the work’s scarred surface, these elements combine to suggest the time-worn hull of a ship, whose cargo must be protected.

The vulnerability and potential loss of material contents also find form in two works from Argote’s for the Willow Pattern series. Made from raw linen, these sculptural paintings hang in looping folds that billow onto the floor. Evoking the sails of a galleon, these fabric forms are embellished with hand-sewn pockets and folds, which create porous containers into which the artist has poured oxide colorants. Reminiscent of the indigo, cochineal, and other natural dyes transported across the world by the Manila Galleon, these pigments pool, seep, and saturate the fabric in ephemeral traces of material circulation and memory.

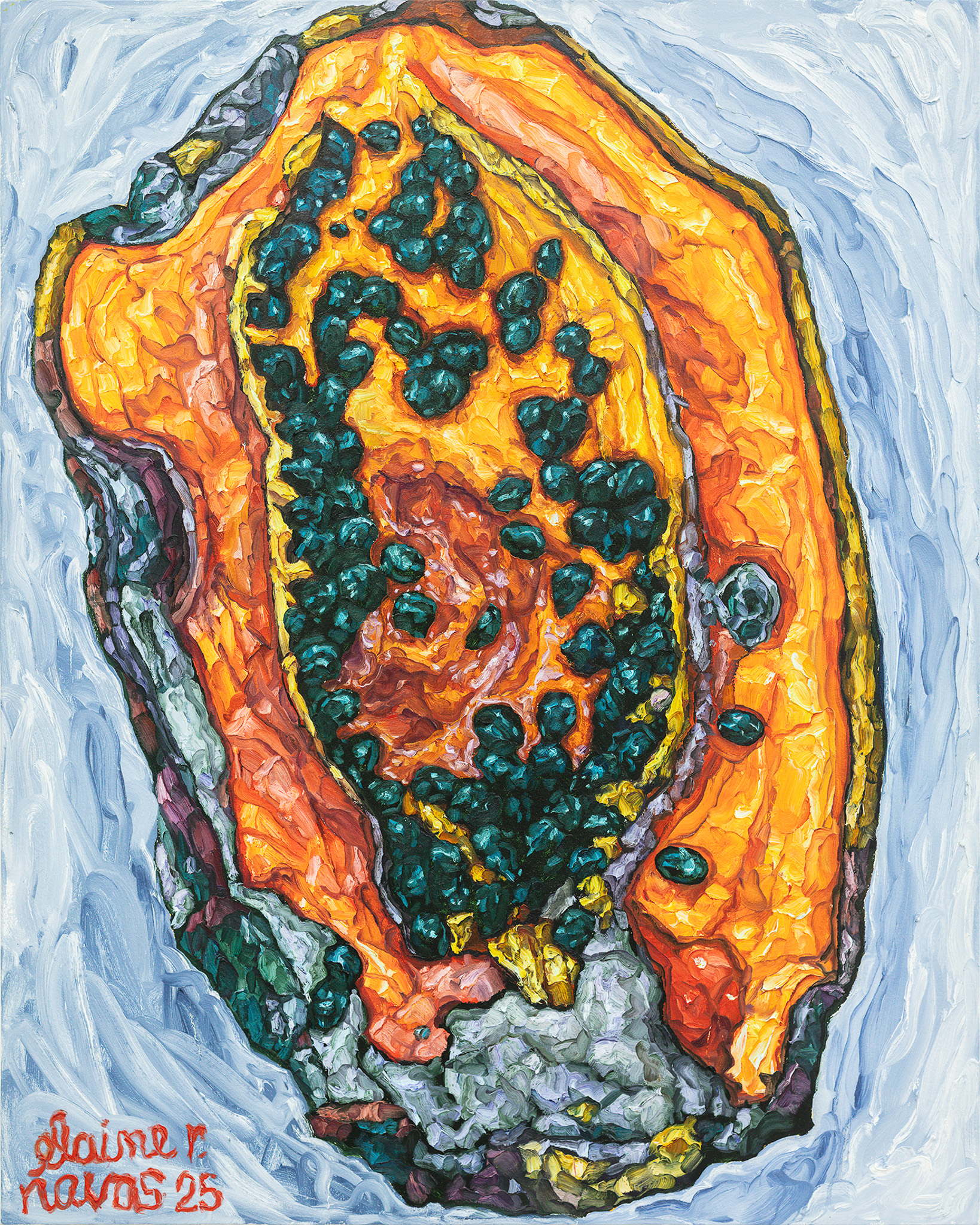

Leaky and stained, Argote’s Willow Pattern series abstractly translates ideas related to the transport and durability of commodities. These issues are also manifest in Elaine Navas’ Bulok, a massive portrait that bisects the Viewing Room at Silverlens. Painted as a large-scale diptych, this work is the latest in Navas’ on-going engagement with the tropical fruit, so ubiquitous to Filipino culture and cuisine. Yet, in contradiction to its quotidian nature, papaya is not endemic to the region, and instead arrived to the archipelago from the Americas via galleon trade. Having been absorbed into local tastes, these exotic origins are today little recognized, and illustrate how the flows of commerce have the potential to be altered and absorbed over time. The possibilities and pitfalls of transformation are further raised via Navas’ subtle painterly gestures, which allude to rot and spoilage. With galleon trade voyages often lasting months from port to port, the susceptibility of such putrefaction remained a distinct possibility. In addition to time, the safe passage of the Manila Galleon was also under constant threat from marauding pirates, mutinies, and shipwrecks.

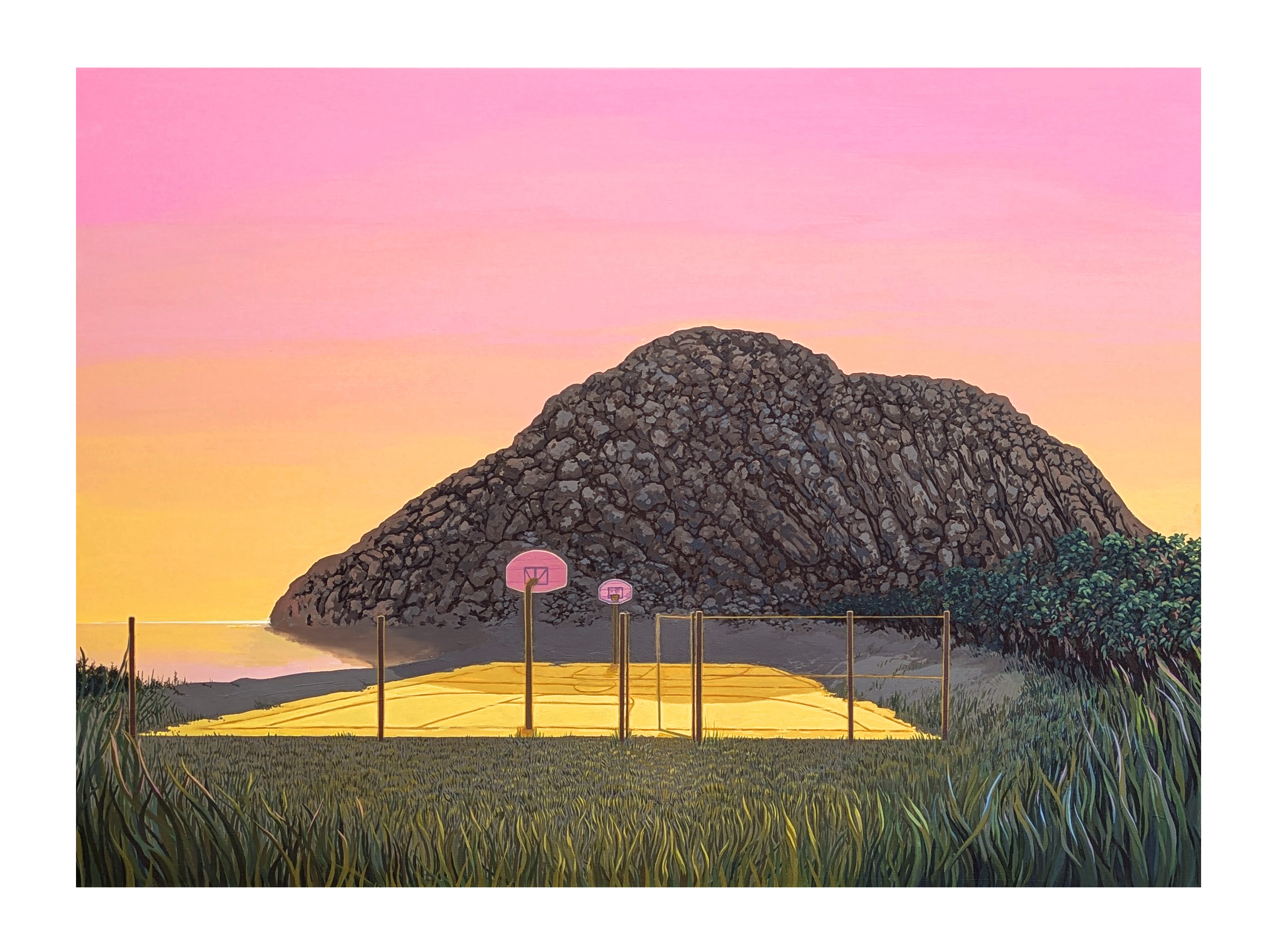

Though the Manila Galleon is today best known for the exchange of goods, the trade route also facilitated the circulation of people – whether as sailors or stowaways, indentured servants or slaves. This movement of bodies is implicated in the paintings by Carlos Villa featured in the exhibition, in which the artist used his own bodily imprint to create dynamic and psychologically fraught compositions. Indeed, though these works do not directly address galleon trade, Villa’s identity as a diasporic Filipino artist whose practice was based in San Francisco, raises similar implicit and indirect connections between the galleon past and our contemporary present as addressed in Barot’s poems. Building off these histories known and unknown, Jenifer K Wofford’s rosy pink and yellow abstractions reflect the artist’s invented mythology around the first Filipino basketball court in the Americas, their arcs and rectangles reminiscent of the game’s three point line. At Silverlens, these works are presented alongside Wofford’s more traditional representation of the basketball courts at Morro Bay Park. This site is recognized as the first point of arrival for Filipinos in the Americas, when crewmembers of a Spanish galleon landed in area in 1587 only to be killed by the Indigenous Chumash people. Reminiscent of Magellan’s death in Mactan, this encounter and its ongoing reverberations via Wofford’s creative practice exemplifies the hold of Galleon Trade and its continued legacy.

(words by Susanna V. Temkin)

Galleon Trade is on view at Silverlens New York from 26 June through 23 August 2025.

Carmen Argote (b. 1981, Guadalajara, Mexico; lives and works in Los Angeles, CA, USA) Argote's installations—including her Searching For The Willow Pattern series and Comforting Object—investigate inherited histories through domestic material and architectural form. Her work draws connections between personal memory and the cultural migration of objects and motifs, particularly those marked by colonial trade. Argote’s work has been in several recent exhibitions, including Flow States– LA TRIENAL 2024, El Museo del Barrio, New York (2024); Holding, Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles, CA (2024); Experimentations: The Art of Controlled Procedures, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, CA (2024); I won’t abandon you, I see you, we are safe, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA (2023); and La Vida Secreta de las piedras, Commonwealth and Council, Mexico City, Mexico (2023).

Patricia Perez Eustaquio (b. 1977, Cebu, Philippines; lives and works in Benguet Province, Philippines) Eustaquio is known for her multidisciplinary works that demonstrate contrasting sensibilities and provide commentary on the mutability of perception, as well as on the constructs of desirability and how it influences life and culture. Eustaquio has gained recognition through several residencies abroad, including Art Omi in New York and Stichting Id11 of the Netherlands. She has been part of several notable exhibitions and presentations at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, Manila; the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, France; and in the 2016 Singapore Biennale. Eustaquio will participate in the Hangzhou Triennial of Fiber Art opening in September 2025. Her work will be featured in Silverlens’ booth in the Premiere sector of Art Basel, Basel in June 2025.

Jorge Rosano Gamboa (b. 1984, Mexico City, Mexico; lives and works in Mexico City) Jorge Rosano Gamboa is an artist based in Mexico City, whose work departs from photographic thinking by expanding through painting, sculpture and installation, pointing to the importance of the relationship between the instant and its representation: the ritual of creating an image, its registration, its methods, and, above all, the very instant trapped in the form of an image/object. His works create fabricated and manipulated spaces and objects where absence becomes visible, as they are composed of images that seem to be suspended because they are only a trace, a remnant or a memory, where image and ghost are one and the same. His recent artistic endeavors delve into the vibrant and multifaceted realm of Mexican and Latin American culture, drawing profound inspiration from the rich artistic traditions of a mixed culture, the narratives of folklore, magical thinking and poetry. His recent solo exhibitions include Bulto/niebla/piel, Saenger Galeria, Mexico City, Mexico (2025); Interwingle Spectre, Lateral, Mexico City, Mexico (2024); En el En-Medio, LaNao, Mexico City, Mexico (2023); and LANDLORDS, Filet Space, London, UK (2018).

Patrick Martinez (b. 1980, Pasadena, CA, USA; lives and works in Los Angeles, CA, USA) Martinez contributes a large-scale, 10-foot-wide architectural painting that melds thick stuccoed surfaces with construction detritus—a visual language grounded in urban histories and cultural hybridity. Supplemented by two smaller existing works, his pieces explore the landscape of Los Angeles through the lens of Chicano and Filipino American identity. Patrick’s work is held in permanent collections such as the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (MOCA), Los Angeles, CA; the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Washington D.C.; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Los Angeles, CA; and the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA), Long Beach, CA.

Elaine Navas (b. 1964, Manila, Philippines) Navas reimagines Magritte’s The Listening Room in her large-scale diptych, replacing the iconic apple with a monumental papaya. Her reinterpretation inserts Southeast Asian imagery into a Western surrealist canon, creating a humorous and poignant meditation on cultural substitution and visibility. Navas completed Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from the Ateneo de Manila University in 1985 prior to taking up her second degree from University of the Philippines College of Fine Arts, graduating with a Bachelor of Fine Arts majoring in Painting in 1991. Navas was the recipient of Honorable Mention (2004, 2002) from Philip Morris Singapore Art Awards, Honorable Mention (1995) from Philip Morris Philippine Art Awards, and Juror’s Choice (1995, 1994) from the Art Association of the Philippines. Her recent solo exhibitions include Each A Small Universe, Drawing Room, Makati City, Philippines (2025); The Boat Is Empty, West Gallery, Quezon City, Philippines (2024); Found Objects, Art Informal, Makati City, Philippines (2023); and It Takes A Village, Finale Art File, Makati City (2022).

Bernardo Pacquing (b. 1967, Tarlac, Philippines; lives and works in Parañaque City, Philippines) Pacquing is an artist broadening the expressive possibilities of abstraction in painting and sculpture. Incorporating diverse found objects that challenge conventional perceptions of aesthetic representation, form, and value, his work displaces the idea of unequivocal forms, introducing possibilities for the coexistence of affirmations and denials. He was twice awarded the Grand Prize for the Art Association of the Philippines Open Art Competition (Painting, Non-Representation) in 1992 and 1999. He is also a recipient of the Cultural Center of the Philippines Thirteen Artists Award in 2000, an award given to exemplary artists in the field of contemporary visual art.

Carlos Villa (b. 1936 – d. 2013, San Francisco, CA, USA) Villa was a San Francisco-born visual artist, grass-roots activist, curator, author, and educator. His groundbreaking artistic career challenged colonial perspectives and laid the foundation for artists to come. Villa received the first-ever major museum retrospective dedicated to the work of a Filipino American artist, which toured from the Newark Museum of Art to the San Francisco Art Institute and Asian Art Museum. Villa’s works were also included at the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts in San Francisco, as well as at the 1976 American Bicentennial. Recent exhibitions of Villa’s work include East of the Pacific: Making Histories of Asian American Art, Amon Carter Museum of American Art (2025) and Cantor Arts Center (2022-2023); Remains of Surface, Silverlens New York (2023); and Carlos Villa: Worlds in Collision, Newark Museum of Art, Newark, NJ and Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, California (2022).

Jenifer K Wofford (b. San Francisco, CA, USA; lives and works in San Francisco, CA, USA) Jenifer K Wofford is an artist and educator who creates work defined by hybridity, history, calamity and global culture informed by her upbringing as a Filipina-American raised in Hong Kong, the UAE, Malaysia, and California, as well as her experience as a longtime educator in a diverse range of communities. She is one third of the Filipina-American artist trio Mail Order Brides/M.O.B. Her interdisciplinary practice encompassing her intercultural education incorporates the intersections and overlaps of drawing, performance, video, web and print. Her work is held in numerous private and public collections, including Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, CA; Meta Open Arts, San Francisco, CA; Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, OH; Nora Eccles Harrison Museum, Logan, UT; San Francisco Arts Commission Civic Art Collection, San Francisco, CA; Hawaii State Foundation on Culture in the Arts, Art in Public Places Program, Honolulu, HI; and the Office of Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi, Washington DC.

Installation Views

Works

In this entirely new body of work, Eustaquio’s materially driven process turns to handweaving massive sculptures of abacá. Also known as “Manila hemp”, the abacá fiber derives from a plant native to the Philippines and was a major trade commodity in the colonial era. It is both fine enough to be woven into fabric for clothing and tapestry and strong enough to be used for shipping cordage, as it has been for centuries—shipping ropes from Manila hemp were not only featured in the almost two hundred galleons built in various Philippine shipping yards and plied the Manila-Acapulco trade route, but also in the thousands of paraws, balangays, and other boats that generations of Filipinos used for trade and travel around the Asian seas. Eustaquio, however, knits the abacá into the structure of a precolonial, gold Philippine jewelry (c. 1000 CE), scaling her works to over one thousand times the size of the original forms.

In this entirely new body of work, Eustaquio’s materially driven process turns to handweaving massive sculptures of abacá. Also known as “Manila hemp”, the abacá fiber derives from a plant native to the Philippines and was a major trade commodity in the colonial era. It is both fine enough to be woven into fabric for clothing and tapestry and strong enough to be used for shipping cordage, as it has been for centuries—shipping ropes from Manila hemp were not only featured in the almost two hundred galleons built in various Philippine shipping yards and plied the Manila-Acapulco trade route, but also in the thousands of paraws, balangays, and other boats that generations of Filipinos used for trade and travel around the Asian seas. Eustaquio, however, knits the abacá into the structure of a precolonial, gold Philippine jewelry (c. 1000 CE), scaling her works to over one thousand times the size of the original forms.