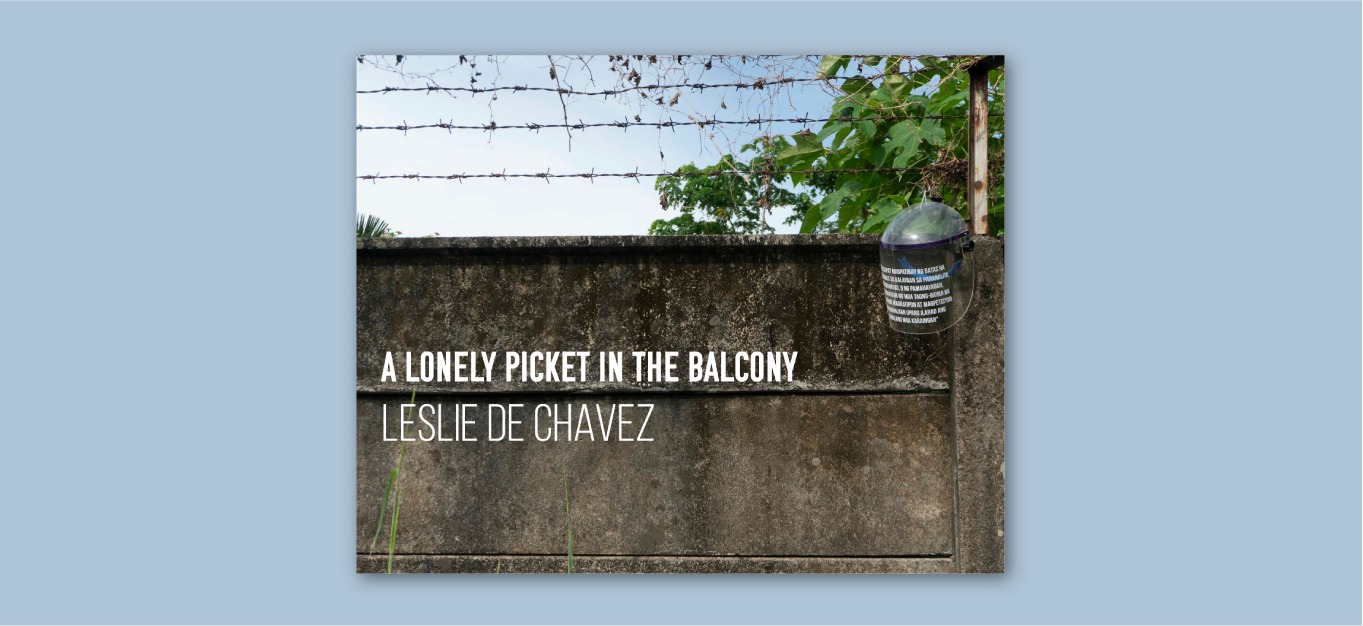

A Lonely Picket in the Balcony

Leslie de Chavez

Silverlens, Manila

About

We are at a critical junction. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated systemic imbalances – political, economic, social, and environmental – which have been festering for some time, all while ravaging the global population. With his latest exhibition A Lonely Picket in the Balcony, Leslie de Chavez presents his dialogical findings of the interwoven causations which precipitated these ‘unprecedented times’. The artist spent the first four months of the world’s longest lockdown in his Quezon home, incapable of producing art; instead, he took the forced hiatus as a moment of respite to reflect on the Philippines’ turmoil. Themes of death, protest, religious exploitation, and economy besieged his quotidian, and has resulted in a deluge of creative output.

A Lonely Picket in the Balcony takes its name from a photographic caption of David Medalla, Mars Galang, and Jun Lansang protesting the 1969 opening of Imelda Marcos’s vanity project, the Cultural Center of the Philippines. [1] The three perched on the first balcony above the CCP’s lobby with signs that read ‘We want a home not a fascist TOMB!’, ‘Abas la mystification. Down with PHILISTINES!’, and ‘RE:GUN/GO HOME’. [2] Though the three were invited to the opening, they remained outside, voicing their dissent against the dictatorship and Imelda’s neoimperial privileging of Euromerican artistic practices at those passing through the door. Indeed, Marian Pastor Roces concisely summarized that despite Imelda’s insistence on showcasing Philippine art at the CCP, ‘[o]utside is where most Filipinos have stayed’ [3] which also poignantly applies to the Marcos’ conjugal dictatorship. With the determination to avoid further antidialogical exclusivity, de Chavez locates his exhibition and protest at the same locus as the trio: at the entryway of a cultural turning point.

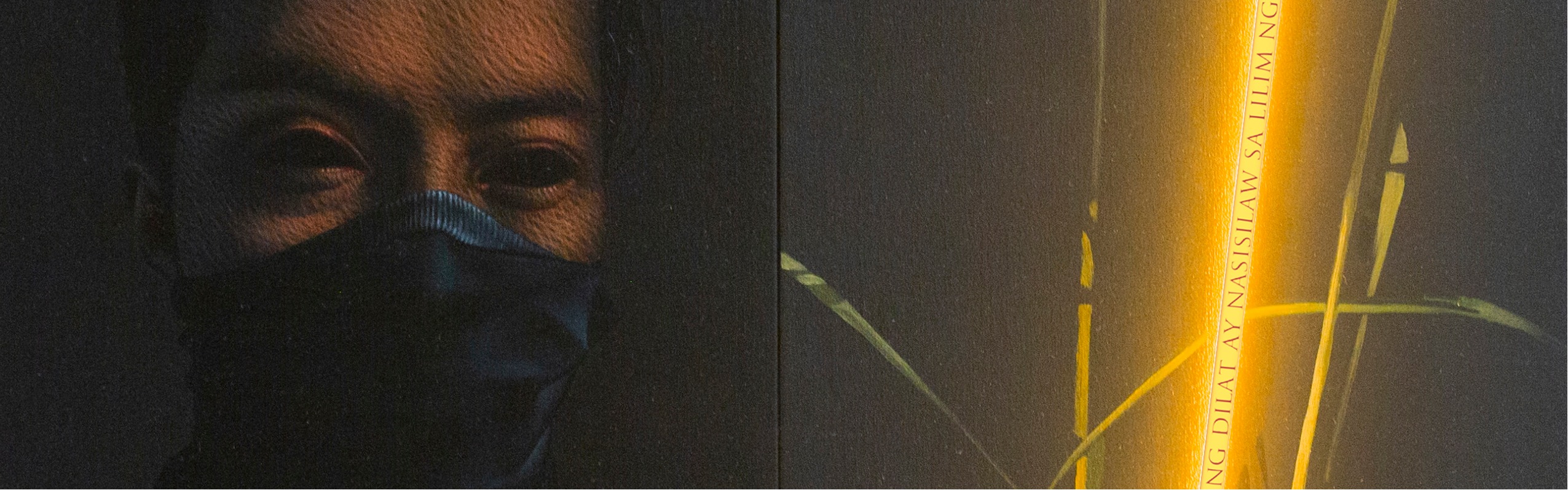

The exhibition begins, and ends, with de Chavez’s Talahib and An Archaic Edifice to the God of Small Things which establish, and subsequently remind, the viewer of de Chavez’s emancipatory agenda against oppressive forces – both physical and ideological. The Philippines has remained tumultuous with dangerous politicians at the head of state for years, simultaneously reeling from the Marcos dictatorship, economic imbalances, social divisions, and the ecological crisis. When President Rodrigo Duterte was elected in 2016, the country entered an era of fear and violence that has since resulted in an unending ‘Drug War’. De Chavez completed Talahib, his self-portrait, in November 2019 to take a defiant stance against the bloodshed: the neon light and talahib stalks boldly signifying his indefatigability despite his missing eyes and covered mouth; the pandemic added further meaning to this diptych, including mask-wearing, isolation, and censorship. Nearby the installation An Archaic Edifice to the God of Small Things [4] acknowledges Marcos and Duterte’s edifice complex where both have proffered grandiose – yet empty – initiatives to hide their corruption. For Marcos, this included the CCP, and for Duterte, his environmental initiatives. Indeed, the ‘God of small things’, borrowed from Arundhati Roy, enacts tumult despite their idolic power – a cautionary reminder as the viewer enters – and leaves – the exhibition.

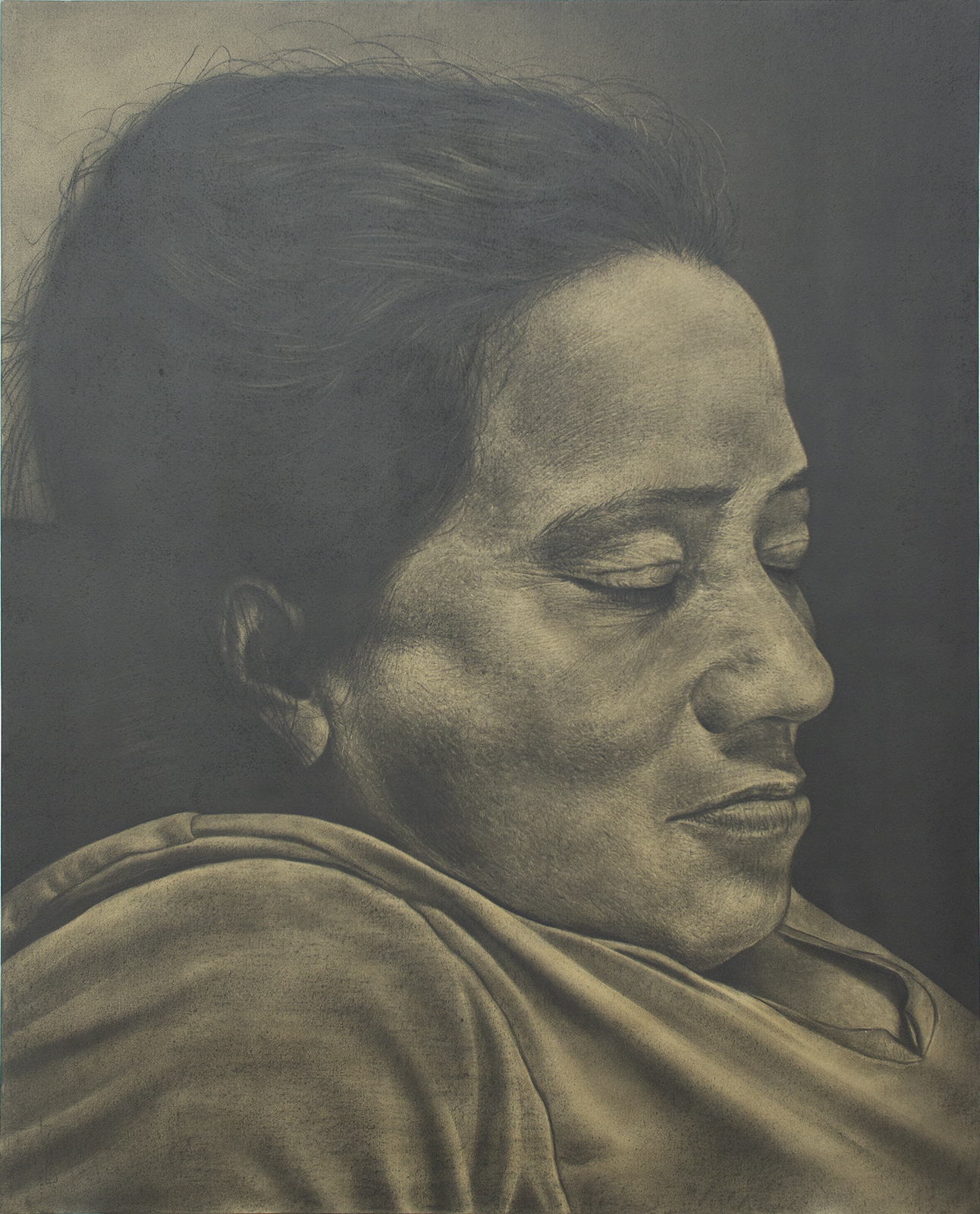

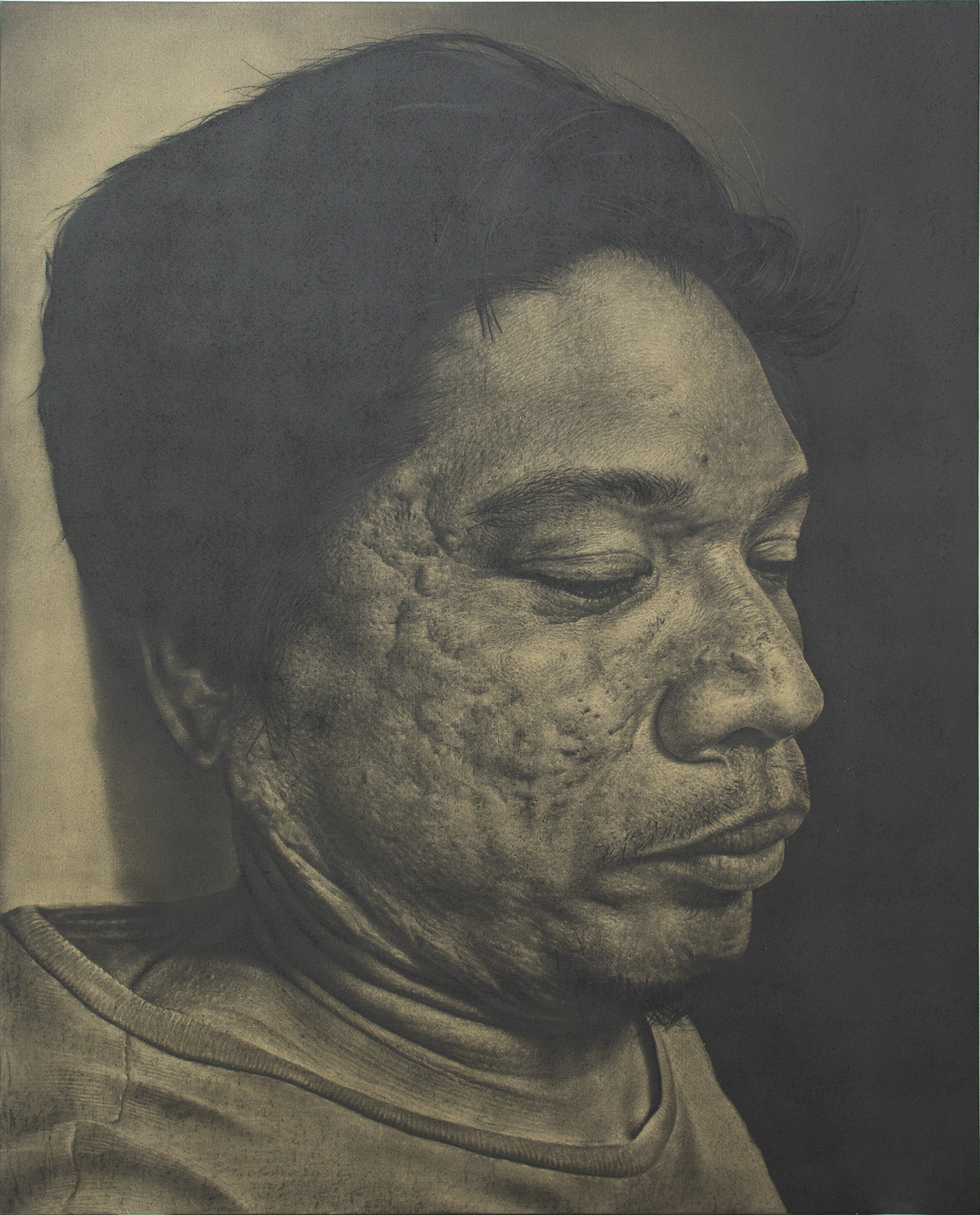

Proximity Series No.1: Jomar and No. 2: Nora echoes this exhibition’s liminality where the viewer is unsure whether the two are alive, their visages permanently suspended in time like death masks. Even before the pandemic, the Philippines was a politically lethal country: installations like Larong Kolateral: Almusal, Tanghalian, Hapunan or To the Persons Sitting in Darkness mourn the many murdered. These numbers increased after Duterte placed the Philippines under ‘Enhanced Community Quarantine’, and his critics have accused him of taking advantage of the public’s distraction and quarantine to justify violence against the populace, [5] as well as implement dystopic policies like the Anti-Terrorism Law. [6] De Chavez condemns these actions in Elehiyang Manhid Nang Sisidlang Walang Malay and Korona at Kalasag, Kalasag ng Korona. The latter, along with Postura sa mga Pagcca Aburidong Ualang Casasapitan, Latigo at Tinik Nang Bitukang Halang, and Ang Pag-uyam sa Dugo ng Paskua further implicate Duterte and Marcos’s exploitation of religion for political gain. [7] De Chavez constantly refers to the Marcos era as this dictatorial legacy continues to reverberate in the present. The artist borrows the Social Realist’s visual language, used during the martial law years as a tool for protest and social change, in paintings like Ang Pag-uyam sa Dugo ng Paskua, Kalakaran bilang Absurd Fascist Semiotics, and Ombrophobia to depict contemporary society’s reality. Lastly, de Chavez reflects on the global capitalist system that economic experts say have further aggravated the pandemic [8] through the lens of his own complicity in the global art market microcosm with I Like Art Fairs and Art Fairs Like Me.

For many, the past year has been a breaking point. The pandemic has illustrated that existing political, economic, social, and ecological infrastructures are defective. This brings us back to the exhibition’s locus: the decisive impasse. With the end in sight for some, A Lonely Picket in the Balcony operates in revolutionary praxis, ideologically and ideally stationed at the interstitial portal between the past and future. With this exhibition, de Chavez encourages those passing through this junction to engage in dialogical reflection and liberating action. As philosopher Paulo Freire writes in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, “Those who authentically commit themselves to the people must re-examine themselves constantly… Liberation is a praxis: the action and reflection of men and women upon their world in order to transform it’. [9]

Words by Marv Recinto.

[1] See Gerard Lico, Edifice Complex: Power, Myth, and Marcos State Architecture (University of Hawaii Press, 2003).

[2] For a detailed first-account of the protest, see Jose F Lacaba, ‘“Down with Philistines!”: David Medalla’s Protest at the 1969 CCP Opening’, CNN, accessed 24 May 2021, https://cnnphilippines.com/life/culture/arts/2019/02/20/david-medalla-ccp.html.

[3] Marian Pastor-Roces, 'The CCP Art and Power Pas de Deux', in Gathering: Political Writing on Art and Culture (Malate, Manila: De La Salle-College of Saint Benilde, Inc, 2019), 20.

[4] Part of this title is taken from Arundhathi Roy’s The God of Small Things where eponymous character causes small “fluctuations” which culminate in catastrophe.

[5] ‘Philippines: “Drug War” Killings Rise During Pandemic’, Human Rights Watch, 13 January 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/01/13/philippines-drug-war-killings-rise-during-pandemic.

[6] Rebecca Ratcliff, ‘Duterte’s Anti-Terror Law a Dark New Chapter for Philippines, Experts Warn’, The Guardian, 9 July 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/09/dutertes-anti-terror-law-a-dark-new-chapter-for-philippines-experts-warn.

[7] For Duterte, see Jose Mario C. Francisco, ‘Challenges of Dutertismo for Philippine Christianity: Revisiting Populism and Religion’, International Journal of Asian Christianity 4, no. 1 (April 2021): 145–60, https://doi.org/10.1163/25424246-04010008. For example of Marcos, see Eileen Guerrero, ‘Cults Began as Political Weapon, Ended Up Deifying Ferdinand Marcos With AM-Marcos Funeral’, AP NEWS, sec. Archive, accessed 25 May 2021, https://apnews.com/article/dd513de8cd2b947ff097e68d49d7de85.

[8] Vicente Navarro, ‘The Consequences of Neoliberalism in the Current Pandemic’, International Journal of Health Services, 7 May 2020, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731420925449.

[9] Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th anniversary ed (New York: Continuum, 2000), 61, 79.

Manila-born Filipino artist Leslie de Chavez has been widely recognized for his incisive and sensible forays into history, cultural imperialism, religion, and contemporary life. Responding to urgent material conditions through his deconstructions of master texts, icons, and the symbols of his times, de Chavez strikes a balance between iconoclasm and an affirmative outlook to the relevance and accountability of art to one's milieu. Leslie de Chavez has held several solo exhibitions in the Philippines, China, Korea, Singapore, UK, and Switzerland. He has also participated in several notable exhibitions and art festivals, which include the Singapore Biennale 2013, 3rd Asian Art Biennale in Taiwan 2011, 3rd Nanjing Triennial in China 2008, First Pocheon Asia Biennale in South Korea 2007. A two-time awardee (2010/2014) of the Ateneo Art Awards for Visual Art, Leslie de Chavez is also the director/founder of the artist-run initiative Project Space Pilipinas, in Lucban, Quezon. He is exclusively represented by Arario Gallery (Korea) since 2006.

“My practice has involved the creation of diverse art forms that scrutinize various issues in Philippine society such as history, colonialism, religion, imperialism, miseducation, power struggle, contemporary culture, politics and social values. My process entails the resurfacing of historical templates, re-examining contemporary social discourse and rediscovering introspection as methods to pin down the truth about the many realities we Filipinos experience. As an artist, I believe that responding through art to our continuous victimization from the chronic conditions of our society can be truly liberating.”

Marv Recinto is a Filipino arts writer and editor based in London, specialising in contemporary art of the Philippines and Southeast Asia. Raised in Manila, Singapore, and San Francisco, she studied Art History and Anthropology in New York and obtained her MA at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London. She is presently the Managing Editor for ARTMargins, MIT Press; a contributing writer to ArtReview Asia; and recently organised / moderated the conference, ‘Art and Democratic Struggle in Myanmar: 100 Days After the Coup’ (Transnation x Arts of the Working Class).

Installation Views

Works

This triptych alludes to the hand game 'bato-bato-pick' to symbolise the current administration’s trivialisation of the national justice system. Being the husband of a public prosecutor, de Chavez is familiar with narratives of injustice and power struggle. These paintings include judicial affidavits; although the text may appear identical, they are of three different cases, reflecting the absence of legitimacy – a ceremony without meaning. Juxtaposing this exploitations are six small tondo paintings contained within the larger panel, referencing the Spanish artist Francisco Goya, who was also critical of socio-political issues during his time. These six studies illustrate a missionary being tested and then exonerated; de Chavez incorporates them into this work to demonstrate the proper way to conduct legal offences. Multi-layered in its application, as well as its cultural and historical references, this triptych reveals not only the artist’s mastery of the medium, but his ideologically rooted practice.

This portrait is a part of de Chavez’s ongoing 'Proximity' series, which is intended to suggest the idea of distance and demise. With the possibility of death becoming all too apparent during the pandemic, interpersonal relationships have virtually ceased; the threat of eternal rest lurks in our collective reality – all within our proximity.

This portrait is a part of de Chavez’s ongoing 'Proximity' series, which is intended to suggest the idea of distance and demise. With the possibility of death becoming all too apparent during the pandemic, interpersonal relationships have virtually ceased; the threat of eternal rest lurks in our collective reality – all within our proximity.

During the pandemic, the local government seized power by implementing destructive programmes that implicated citizens uncooperative to authority. Outraged by their insensitivity – utilising the health crisis as an opportunity to strengthen their party – de Chavez created this installation. The main piece, modelled after a cadaver bag, has become a common symbol due to the escalating deaths caused by COVID and extrajudicial killings. Using dry pig intestines, the artist invites his audience to consider the interior of the administration, which he believes is marked by slaughter and corruption.

In 2020, at the height of the health crisis, the Philippine government introduced the Anti-Terrorism Act, which could incarcerate any citizen expressing criticism against current political leadership. It was during this period of oppression, reinforced by the nation-wide lockdown, that Leslie de Chavez conceptualised this installation. Highly symbolic, the piece itself – a torn crown situated within a face shield – represents the pandemic’s effect on society’s social situation, inhibiting one's physical freedom. This notion of captivity is further emphasised by the government’s subjugation of local press and free speech, which de Chavez alludes to through the text displayed on the face shield: a section from the Bill of Rights, reminding people of their prerogative as citizens.

This work is a commentary on current Philippine president, Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs. Constructed in concrete to resemble a brutalist structure, this installation takes the form of a sungka board. In equating this socio-political conflict with a game, de Chavez makes a clear statement on the present administration, specifically in the violent treatment of its citizens, symbolised here by slippers collected from a dumpsite. The objective of sungka is to occupy your opponent’s territories, which de Chavez points out is applicable to the war on drugs, one that claims the narratives and positions of regular people – victims who become collateral damage in the power play of the mighty.

This work is a commentary on current Philippine president, Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs. Constructed in concrete to resemble a brutalist structure, this installation takes the form of a sungka board. In equating this socio-political conflict with a game, de Chavez makes a clear statement on the present administration, specifically in the violent treatment of its citizens, symbolised here by slippers collected from a dumpsite. The objective of sungka is to occupy your opponent’s territories, which de Chavez points out is applicable to the war on drugs, one that claims the narratives and positions of regular people – victims who become collateral damage in the power play of the mighty.

This towering installation entitled ‘To the Persons Sitting in Darkness’ was first exhibited in de Chavez’s 2018 exhibition, The Allegory of the Cave at the Arario Gallery in Shanghai, China. The work itself is composed of nearly two hundred portraits, silhouettes of males and females, from the District Penitentiary of Lucena City. Accompanying these images are the inmates’ names, as well as a clothesline of yellow shirts that symbolise their uniforms. The triangular composition of these photographs suggests the pyramidical power structure of the present government administration, and is intended to address the Filipino people, who the artist believes reside in darkness – even those outside prison walls, who conduct their lives under the illusion of freedom.

SLG_LDC024

This installation references the Marcos regime, which constructed grandiose institutions, such as the Cultural Center of the Philippines, to represent their administration – a strategy being replicated by current president, Rodrigo Duterte. Incorporated into this work are colourful little resin blocks, suggesting natural resources, that were inspired by the computer game, Minecraft, where worldmaking is the objective and big ideas are reduced to basic units. Reinforcing the concept of structure, de Chavez likewise includes aged concrete into the work, which itself is in the form of a religious structure, an altar. A symbolic representation of the government, this work ultimately juxtaposes religion and corruption to encapsulate the deplorable state of the country.

SLG_LDC022

This self-portrait was created as part of a 2019 portrait exhibition that the artist organized in his hometown of Lucban. de Chavez paints himself as the artist who is critical and non-conforming; being able to thrive wherever they are placed—in this case the figure looks out with deep and hollow eyes into tall grass (talahib) illuminated by light. On the neon light a short passage is written: “hindi lahat ng dilat ay nasisilaw sa lilim ng pangakong liwanag” referring to those who view promises of change with a critical lens. The artist had no inkling of the 2020 pandemic, but the covering that obstructs the lower half of his face is both a coincidence and foreshadowing.

SLG_LDC011

Installation Views

Works

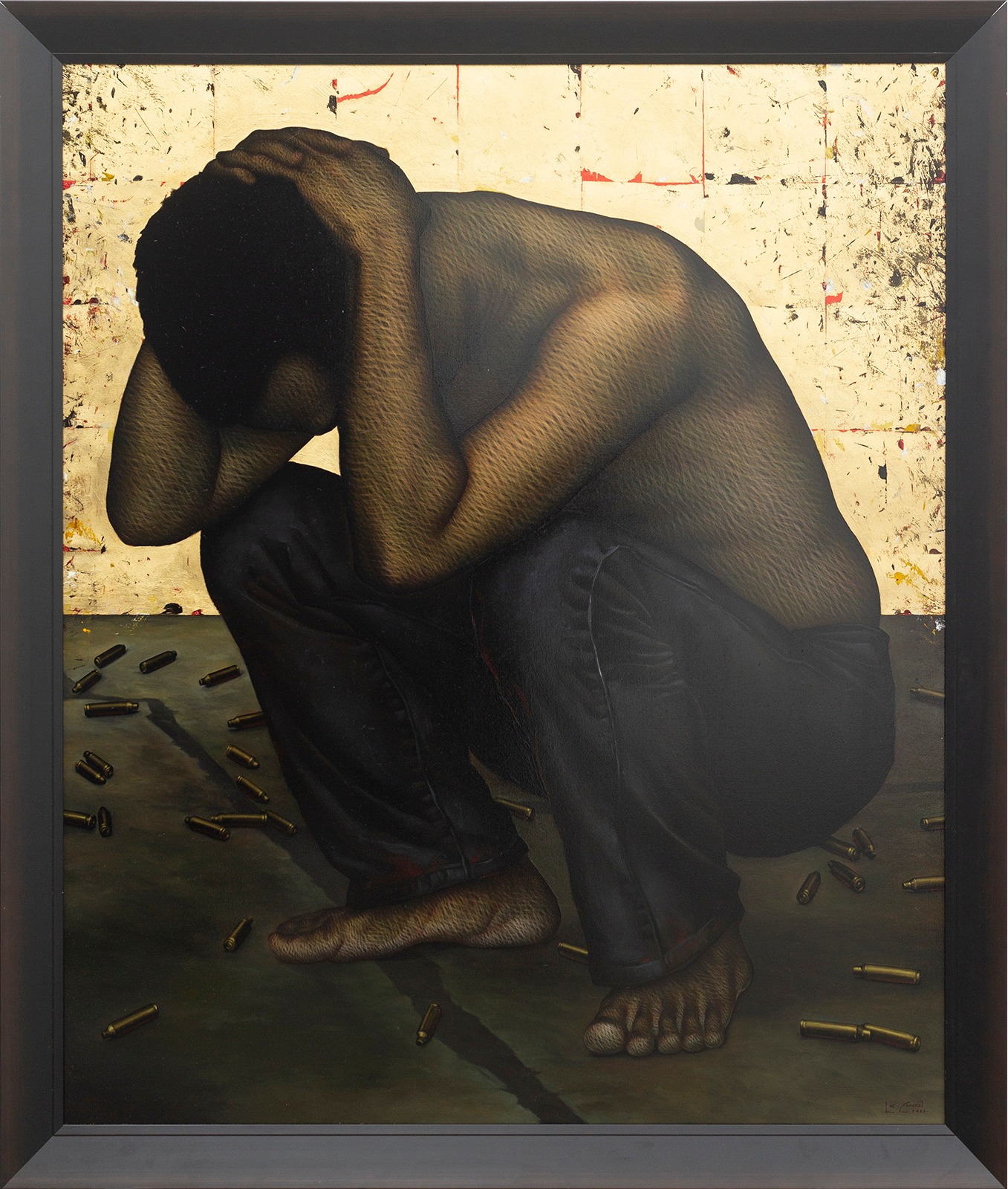

In keeping with his sociopolitical oeuvre, de Chavez remarks on the violence of the government in this painting, as well as those most vulnerable to their systemic injustice: the poor. The lone victim shields himself from torrential bullets, a metaphorical reference to the extrajudicial killings that have come to characterise the current administration.

Evoking a flag commonly found in religious processions, this piece is made of dried pig intestine with an ink drawing of Christ at its center, appropriated from Albrecht Durer’s Man of Sorrow, Seated. Surrounding Christ’s head is a prayer written in gold leaf, forming a halo. The text is derived from 19th century revolutionary Apolinario de la Cruz, better known as Hermano Pule: a Filipino who founded his own religious order as a means to fight Spanish racism and suppression. The work touches on themes of faith and fanaticism.

SLG_LDC018

Fashioned after a rosary, this massive sculptural piece is a contradiction that plays on themes of the sacred and the profane. Upon closer inspection, the object of devotion loses its meaning and becomes a threatening artifact. Heads of Philippine Presidents Rodrigo Duterte and Ferdinand Marcos replace the beads; the cross is fashioned out of molded .38 caliber guns—weapons commonly found in crime scenes related to extra judicial killings in the country—with an encapsulated fist made of decaying plaster of paris at its heart.

SLG_LDC015

This satirical installation is the artist’s mocking commentary on capitalism, which he regards as the root of the virus, the vehicle of the pandemic. A pun from Joseph Beuys’ 1974 performance exhibition, ‘I Like America and America Likes Me’, de Chavez employs this word play to question how the general public views and consumes art, in connection to their relationship with the health crisis. Critical of the global art world, which participated in the spreading and transference of the virus, de Chavez also reinforces its contribution to the propagation of capitalist structures. Loaded with symbolism, this interactive work condemns the objects, apparatus, and establishments that engage in the destructive system that actively damages the natural world, displaces resources, starts wars, and widens the gap between socio-economic classes.

SLG_LDC021