About

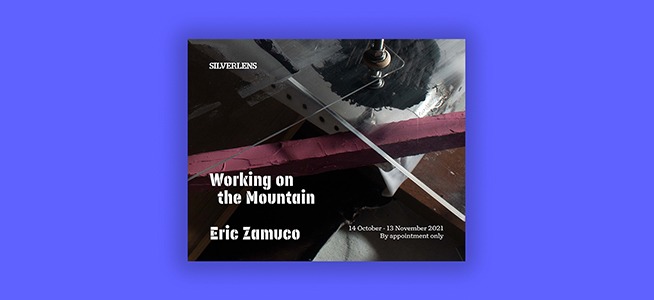

Silverlens is pleased to present a new show by Eric Zamuco called Working on the Mountain taken from the title of a book on writing by N.V.M. Gonzales. In one of the essays, the creative process is compared to the carving of ancient temples found in Ajanta, India.

To work on a mountain is to work in precarious conditions, knowingly accepting the risk of collapse amid an indomitable landform. Zamuco relates this process to his art practice where he believes painstaking construction and deconstruction of reality can illuminate the everyday. This meditative unraveling is seen in the five mixed-media assemblages made from gathered studio detritus and leftovers from days marking life spent in isolation. The new works display the artist’s distinctive technique which began developing as early as 2001 during his art residency at the Vermont Studio Center in the United States.

Each “Templo” is a compound of linked plexiglass sheets, wood, and metal rods. The threaded rods hold seemingly random objects and images together at first glance but relate by way of the medical shorthand or cursive codes found in each one. The abbreviations are painted as thick brushstrokes. In the first Templo, the scribbled code in black means vaccine while the one in white is terminology for detached. The work is predominantly black and white varying in gathered texture and material that looks more like they are shifting than floating. There is a surprising image of fish heads tucked in at the second layer and a ghostly impression of chain links peeking just above the base. Zamuco uses the medical terms as compositional totems to guide which disparate elements could be associated together. The viewer is reminded how in the context of a pandemic, the names for medical conditions have seeped into the lexicon of ordinary conversation.

On the other hand, “Templo 2” with the word wound gathers pressed purple leaves, a spoon, a disintegrating pink rag, and an image of an empty sink among other objects. A purple rod slices across the work to its side as if to give the spatial arrangement some volume where the top of the work is heavy and the bottom tapers in. It is meant to be topsy-turvy by being physically and visually disorienting. Zamuco says he thinks of the Templo series as inverted stupas or ziggurats tiptoeing on their apexes.

These ideas of instability and uncertainty somehow held by a center we cannot see are further explored in the rest of the works. “Templo 3” contains two codes combined to mean corpus or body. There are Polaroid shots of doorknobs, a printed image of a stiffened paintbrush, and weathered woodwork along with a chipped yellow number sign. Photography is one of the artist’s adept mediums of choice and the images used here are domestic and solitary though not necessarily foreboding. For “Templo 4,” the selected shorthand is scribbled in light blue for the word, paralysis. The sequence of the objects feels looser here with much of the accretion concentrating on its peripheries. On closer inspection, there are small corroded hands drilled to wooden slats with blue patina protecting its bronze form. The artist also introduces line drawings of single blocks on plexiglass sheets as if they were thrown haphazardly and not used to build.

The mass of materials intensifies for “Templo 5” making it look more of a layered short ladder. For this assemblage, the shorthand codes used are for the words: oxygen, immune, and transfusion. Miniature silver leaf cut-outs of a person standing and gesturing are dotted throughout the work. The multiple line drawings of bare feet splayed outward or feet bound by tape or the soft flesh of soles visible are unsettling. They are based on the photos of EJK victims found in news reports with their identities hidden and only their arms and legs visible. This is the last of the Templo iterations but it does not seem like a conclusion but rather a flashback to pre-lockdown times, to a recent past interrupting our collective present tense concerns but no less important because it is part of the story now.

Just as sites of worship make distinctions between the sacredness of what is inside and the profaneness of the world outside it, so does Zamuco do away with this segregation. The rituals and rhythms that define an ordinary life in terms of words, objects, images and unpredictability are transformed into an opportunity for contemplation where the profane is made sacred.

- Josephine V. Roque

Eric Zamuco’s (b. 1970, Manila, Philippines) body of work has been about filtering the unfamiliar, responding to circumstances from a particular time and place, through arrangement/assembly of a hybrid of ordinary objects, materials,processes and imagery. Zamuco’s themes run the gamut from ideas about dislocation, identity, post-colonial narratives, spirituality, geo/politics to the need for reclamation of space. His works,which are of a diverse range of media, including sculpture, installation, photography, drawings, video and performance, serve not only as social commentary but also as self-critique. The intention in transforming the commonplace is to pull the immaterial and possibly find knowledge for some kind of human order.

Zamuco was a recipient of the Thirteen Artists Award (2003), the Ateneo Art Award (2005), holds an MFA in Sculpture (2009) from the University of Missouri-Columbia. He was an artist-in-residence at the Centre Intermondes, France in 2015. Working on the Mountain is Zamuco's 6th solo exhibition at Silverlens Gallery.

Josephine V. Roque is a writer and lecturer based in Manila. Her first book of essays was recently published by Penguin Random House SEA.

Works