Installation Views

About

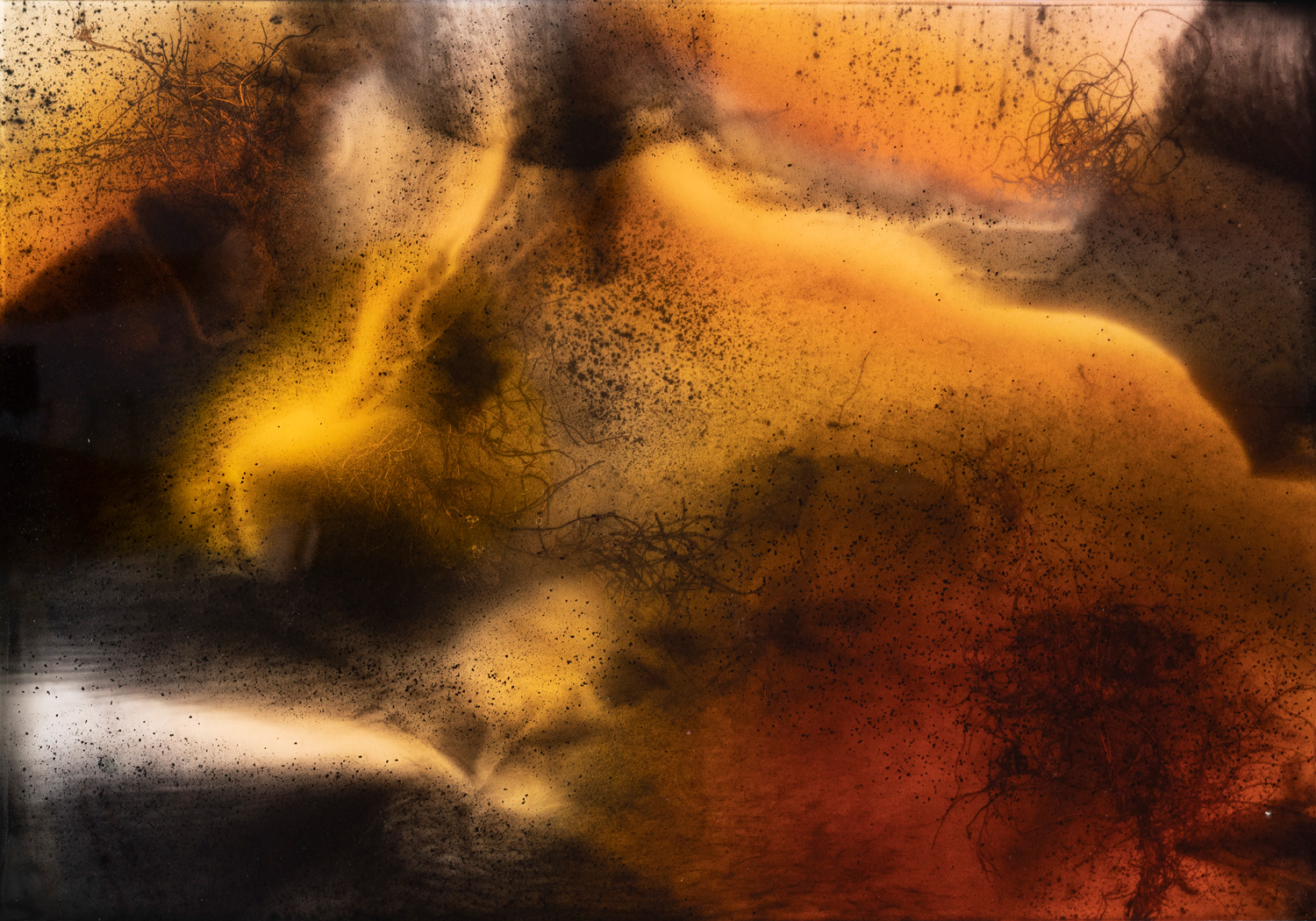

Find all-over paintings and rock-like fragments that have thick amber surfaces. Do you know about the high demand for palm oil and how it’s in lipsticks, detergents, and ice creams? How about the smoke and haze from burning forests that make way for more palm oil plantations in Asia, Africa, and South America?

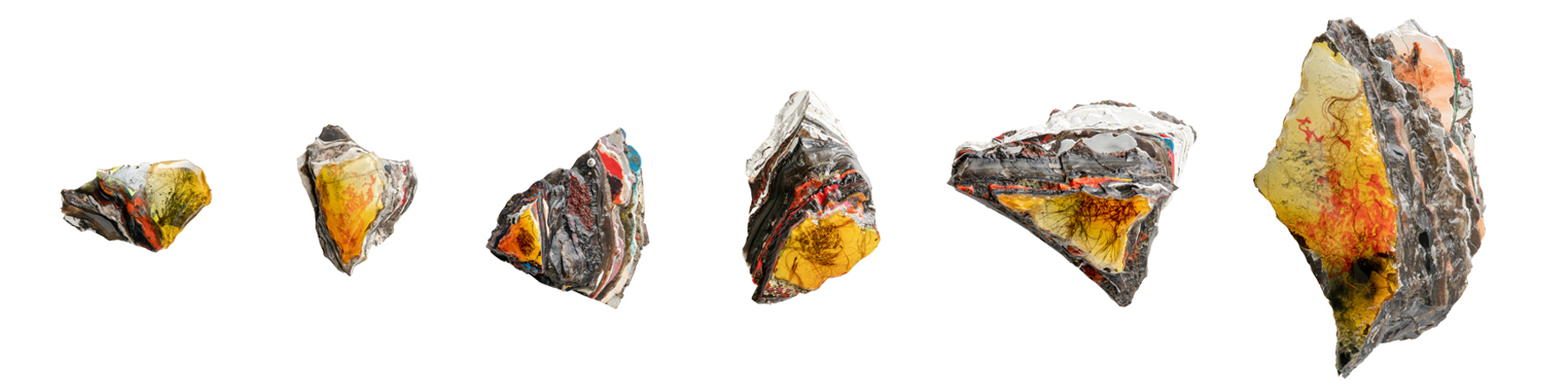

The artist behind these paintings and sculptures, Arin Sunaryo, seems to be more about making than lecturing. He probably wouldn’t dwell on environmental doomsday scenarios. Instead, he might tell you about his studio table in Bandung, Indonesia. He had been using it for more than twelve years and was ready for a new one. Over time, he had covered it in piled-up layers of excess paint, resin, and other sundry materials. The sediment was so thick around the table, he and his studio assistants had to carve the table out. The chunky fragmentary remnants from around the table are historical records of a studio life of mixing, pouring, dripping, splashing, coating, and encasing.

Sunaryo frequently uses resin as a preservation agent along with unusual materials: palm oil, but also volcanic ash, sugar, and shrimp paste. Fried eggs don’t work. Even encased in resin, they smell. Chili powder produces small bumps on the surface of the resin. With turmeric, the resin won’t set.

Sunaryo is fascinated by how people want to freeze time and attempt to preserve things for the next generation. He says he tries to make any material neutral before he works with it. He wants each painting to have an energy all its own. He doesn’t want to force anything but lets materials speak for themselves.

Find a whirring projector without film. Its unaltered light hits the wall. Nearby, a vibrating metal sheet. Hear reverberations from the metal that reshare a loaded song from across time—Nabasag Ang Banga (The Jar Breaks), part of the soundtrack for arguably the first Filipino feature-length film, 1919’s Dalagang Bukid (The Farm Girl), which is now lost. The song’s lyrics suggest a rape by a man who claims he is in love but won’t take no for an answer. The jar that breaks is an awkward symbol for virginity.

“‘Do not pester me,’ the lass decried.

‘But I am in love,’ the man replied…

When I told him to be careful, he snatched my jar. So I’ve come home without water, and my dress is muddy.”

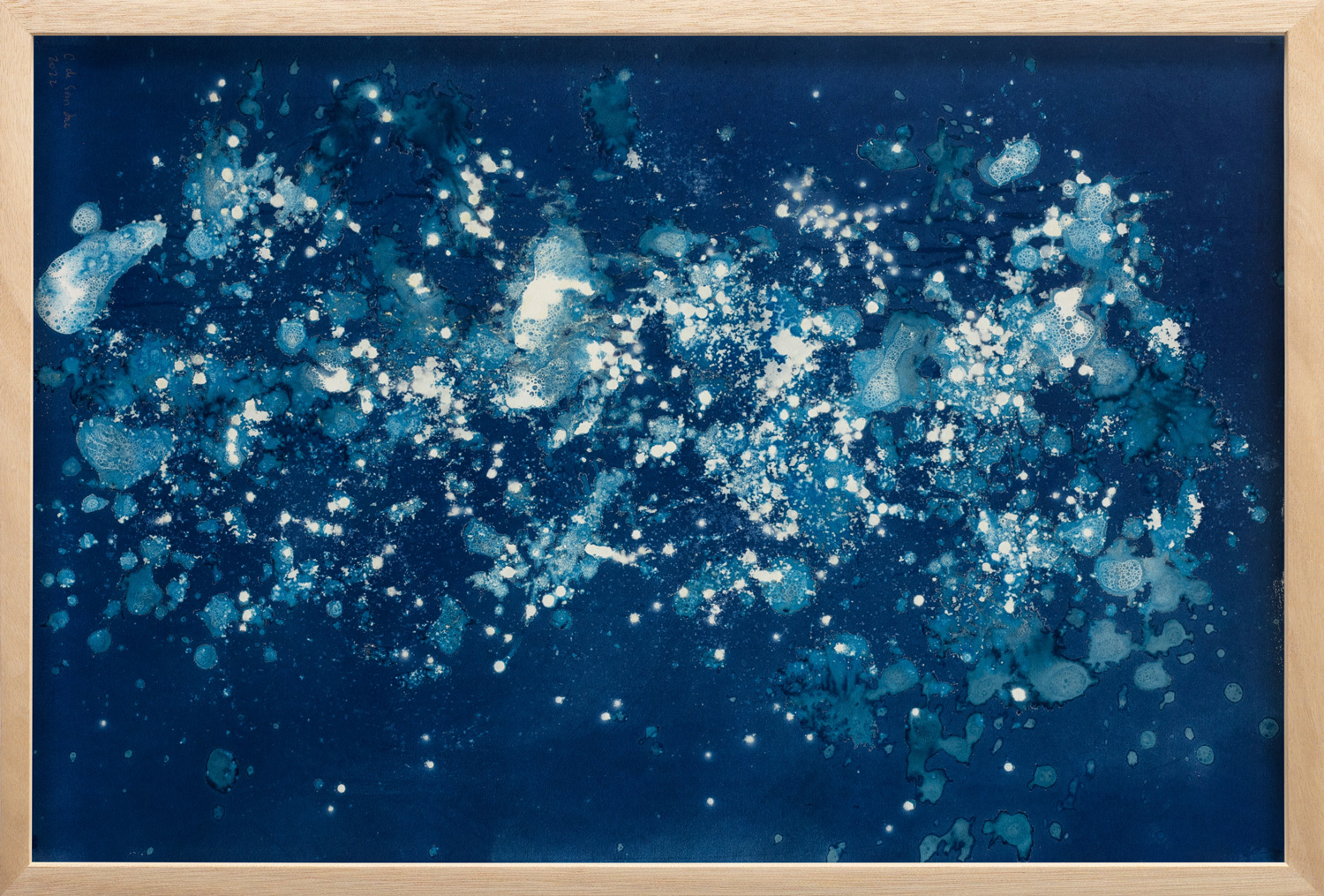

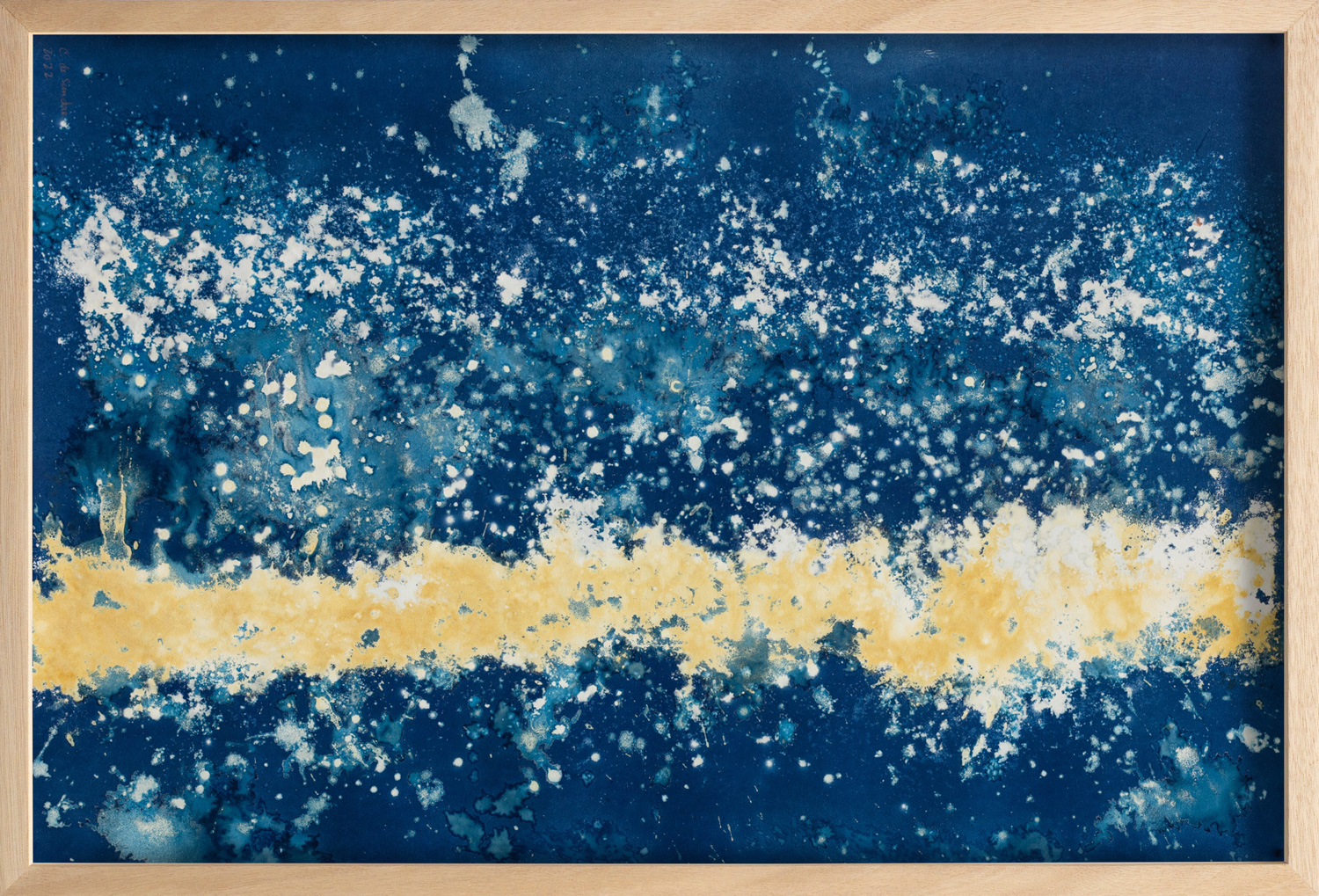

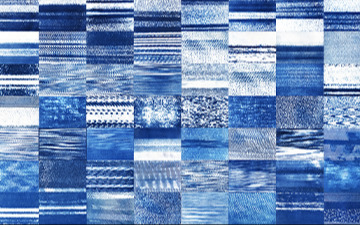

The music accompanying these lyrics is tra-la-la pastoral, evidence of a culture that infantilized and objectified Filipinas. The sound you’ll hear now you’ll find hazy. Think of a far-off voice, a staticky, singing ghost. Nearby are cyanotypes that rework scratched and otherwise degraded film reels.

The creator of this work, the artist and sound designer Corinne de San Jose, is troubled that Ferdinand Romualdez Marcos—the son of dictator Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos—is the new president of the Philippines. In a recent conversation, de San Jose described her general mood as, “What the fuck happened?” In preparatory notes for this exhibition, she writes about how place and history are among her materials. She describes her view of the Philippines this way: “Recent events in the country’s political scene bring to light an apparent need to reassert the past as we find ourselves in a dystopic loop with our history. We have forgotten our past.”

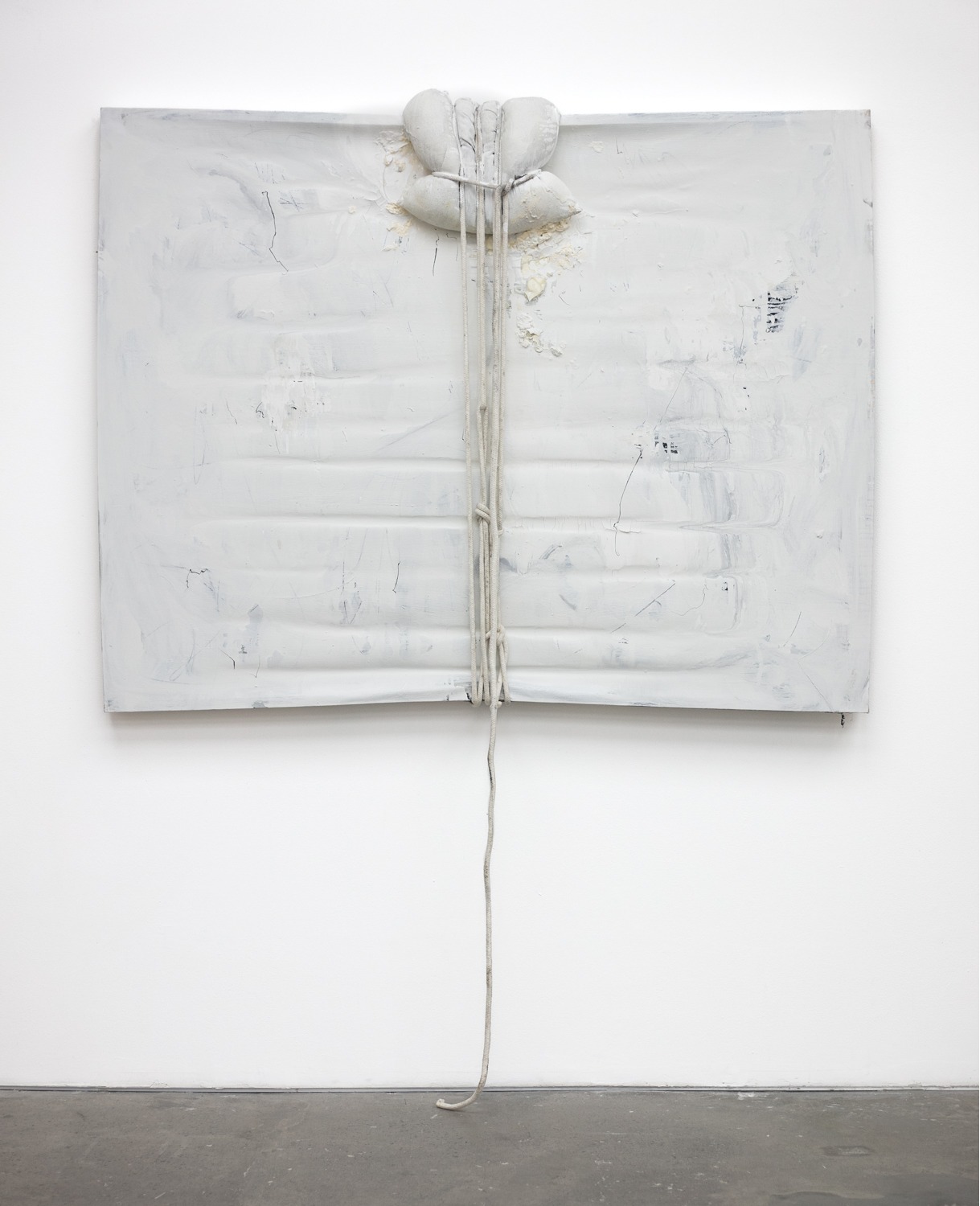

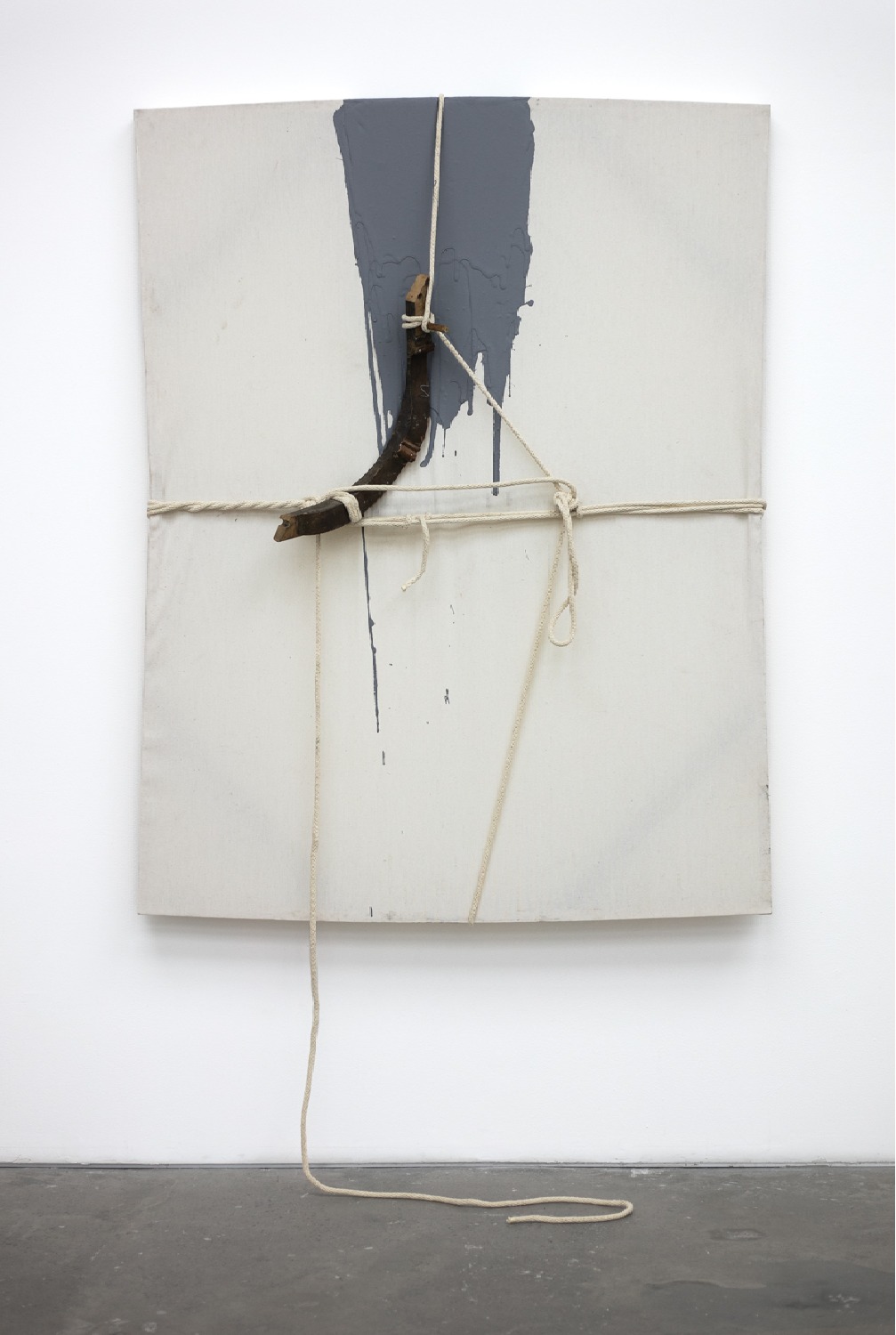

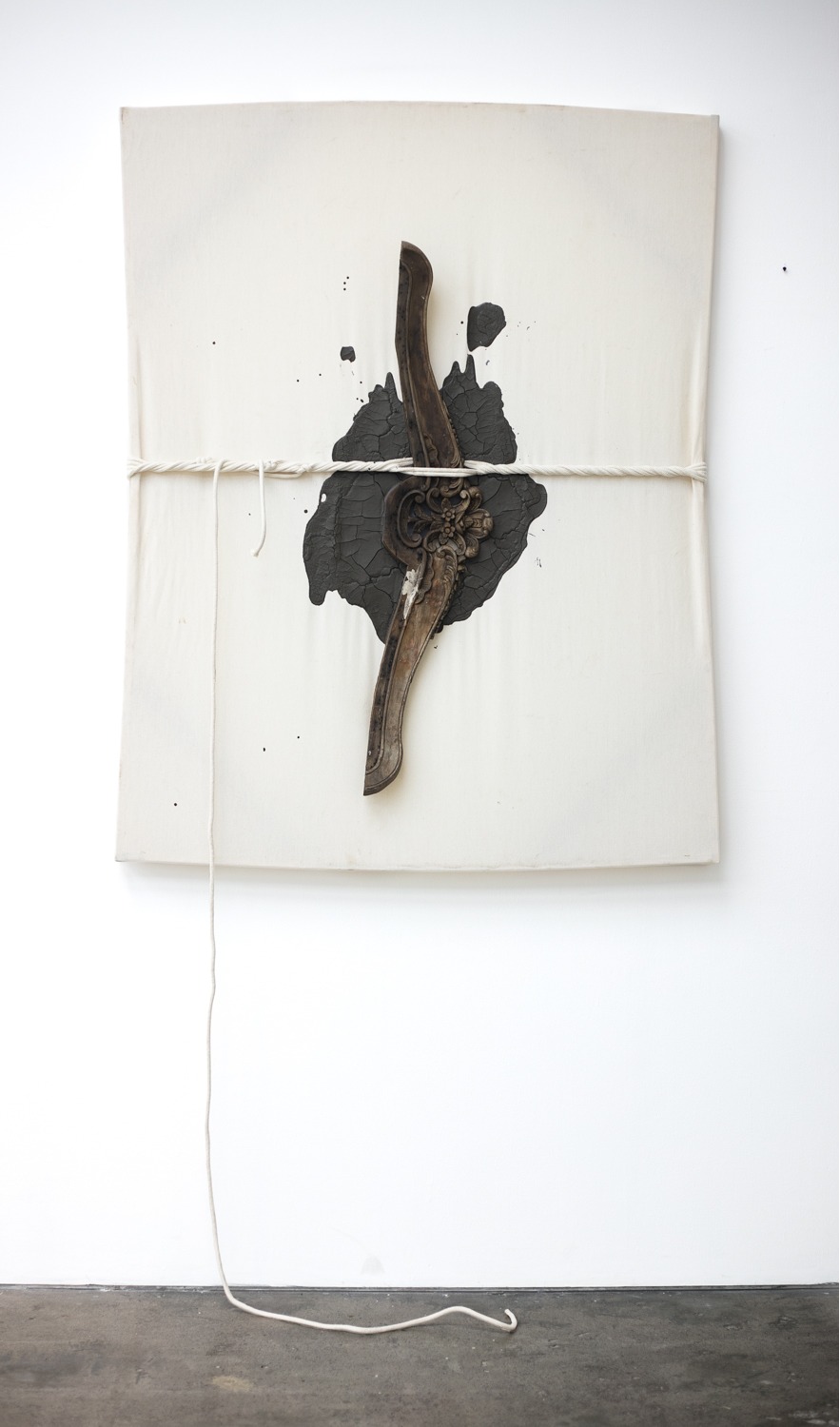

Find a series of recent white and gray canvases involving scribbles and drips of industrial paint. They forgo illusion and appear to endure considerable tension. One features a clamp holding a paintbrush pressed into a pillow hardened with paint. Another is cinched, bent out of shape by rope and a system of knots wrenching the painting’s stretcher bars and holding an antique-looking wooden fragment that was maybe formerly part of the seat back on a nice chair.

Bernie Pacquing, the architect of this series, will tell you how he studied advertising in school but found it rigid. He didn’t like how everything had to be perfect, so he handed in his school assignments on plywood. These days, combination and contradiction are central to him. He melds rough or loose gestures with tightness, precision, and stiffness.

Pacquing’s practice is antithetical to the corporatization and technocratic dehumanization currently circumnavigating the globe. In his home studio in Manila, Pacquing welcomes fluidity, miscibility, rust, and mold. He piles up collections (including film reels de San Jose selected from while making her cyanotypes). And, all around him, he sees layers of indexical marks that remind him of paintings. He loves the flood lines on city walls and underpasses, political scrawls, peeling posters, and mud splashes. Yet, he listens to precise classical music in the studio—lately recordings of Yehudi Menuhin playing Bach’s partitas on the violin. When I spoke with Pacquing, he’d just returned from Singapore, a place he found not just sanitized but ordered to the point of sterilization, largely absent of what sustains him.

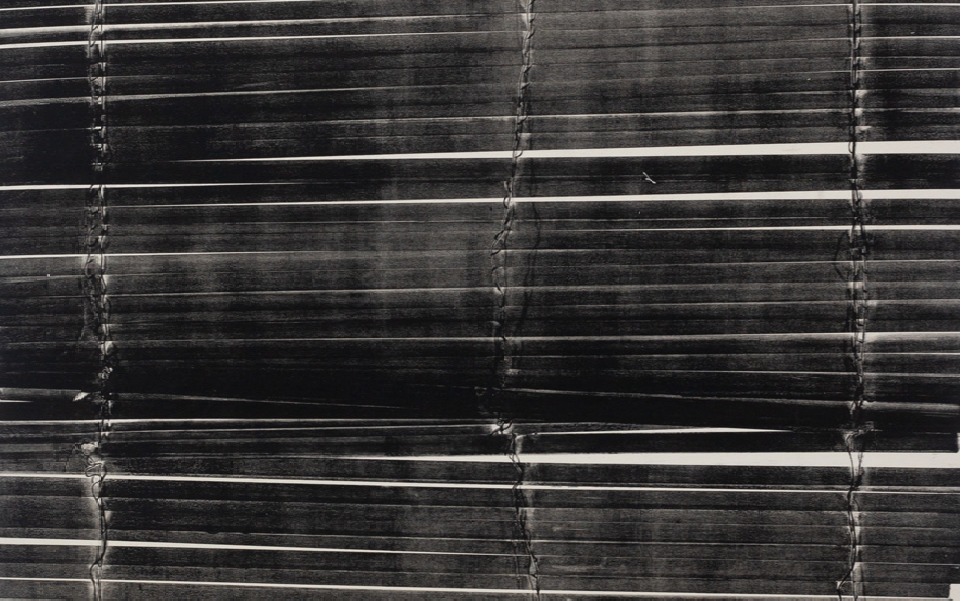

Find a large monoprint on canvas showing an impression left in ink by Venetian blinds. The artist Nicole Coson broke her etching press when making it. She also injured her knee in the process. Coson will ink up blinds, lay them on a piece of canvas, and run that through her press, one of the biggest in London. It’s hard to pull huge monoprints through an enormous printing press, especially prints on canvas.

Coson, who grew up in the Philippines and moved to London for school when she was seventeen, told me she thinks of the etching press as a painting tool and that this way of working developed during quarantine. “I was feeling like the edges of our bodies were beginning to blur,” she said. “We were these soft bodies that needed to be protected inside. Our concepts of private and public were shifting.”

Think about inside and outside, frustration, claustrophobia, and how opening and closing blinds can mark time. Think about home as a refuge versus home as a prison.

Coson’s works are about more though. Where do our bodies stop and start? Think about windows and blinds and negotiating visibility, how and when you are discernable, why, and for whom. By extension, think about subjectivity, not being classified, put into a taxonomy, or forced to make sense. Coson says, “Sometimes an artist’s ethnicity and race precede the work and render the artist’s ability of individual utterance invisible and unheard.”

In External Entrails, internal is external, and external is internal. The abstractions of Coson, de San Jose, Pacquing, and Sunaryo are individual, complex, and invigorating.

– Marcus Civin

Nicole Coson (b. 1992, Manila, lives and works in London) aims to examine the concept of invisibility, not only as a passive position as a result of erasure, the problematic dichotomisation of culture but also its potential as an effective artistic strategy. Can invisibility be seen not just as a disability but as an advantage or ability? Like the optical survival strategies utilized by both prey and predator in the natural world? Who can benefit from this tactic of concealment and dissimulation and how can one apply these strategies?

In her work, Coson explores the economies of visibility and disappearance in the case of overlooked bodies, invisibility in warfare as tactical countermeasures, and cultural visibility in art. Coson’s work searches for a productive position within invisibility that lends us an opportunity in which we are able to negotiate the terms of our visibility. To vanish and reappear as we please and as necessary to our own personal and artistic objectives, to effectively disappear amongst the grass blades until the very moment we must break that illusion, the very moment when it is time to strike.

Corinne de San Jose (b. 1977, Bacolod, Philippines; lives and works in Manila, Philippines) is an award-winning film sound designer and multidisciplinary artist, whose works deal predominantly with the photographic realm. Her images, whether animated or static, are heavily anchored in processes of time – fluid, malleable, and experiential. There is both a self-reflexively sculptural and performative aspect to de San Jose’s work as she documents varieties of alteration through her recurring subjects, such as the female body, whilst analyzing how it changes them. De San Jose’s visual aesthetic is principally impacted by sound. Specifically, silence in relation to noise as she orchestrates pieces that boast quietude in an increasingly deafening world. Furthermore, the temporal and rhythmic idea of repetition, incorporating visual grids as a method to manage and organize time and progressions in storytelling.

De San Jose has presented several solo shows in Silverlens, the most recent of which is Little Blue Window in July 2020. De San Jose is a respected sound designer, with multiple awards in her career.

Bernardo Pacquing (b. 1967, Tarlac, Philippines; lives and works in Singapore) continues to approach the expressive potential of abstraction in painting and sculpture through the use of disparate found objects that confront and disrupt perceptions of aesthetic representation, form, and value. By focusing on the organic shapes of visual reality, his work displaces notions of indisputable forms and opens possibilities for coexisting affirmations and denials.

Pacquing was born in Tarlac, Pampanga in 1967. He graduated from the University of the Philippines College of Fine Arts in 1989 and was twice awarded the Grand Prize for the Art Association of the Philippines Open Art Competition (Painting, Non-Representation) in 1992 and 1999. He is also a recipient of the Cultural Center of the Philippines Thirteen Artists Awards in 2000, an award given to exemplary artists in the field of contemporary visual art. Pacquing received a Freeman Fellowship Grant for a residency at the Vermont Studio Center in the United States. He lives and works in Parañaque City.

Arin Dwihartanto Sunaryo (b. 1978, Bandung, Indonesia; lives and works in Bandung) received a Bachelor’s Degree in Painting from the Bandung Institute of Technology (2001) and a Master’s of Fine Art at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, London (2005). He is particularly interested in the utilization of resin as a medium that conserves minerals, pigments, and other particles. He concentrates on the idea of expanding painting through investigating its core constituencies and forms. Recently his practice has begun to incorporate elements of video and new media, as well as sculpture. Arin’s work has been featured in numerous exhibitions in SouthEast Asia, Europe and the United States including an exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York back in 2013. He was also nominated as a finalist for Best Emerging Artist Using Painting by the Prudential Eye Awards in 2015.

Works