Shrines

Catalina Africa, Poklong Anading, Santiago Bose, Chati Coronel, Patricia Perez Eustaquio, Kawayan de Guia, Lani Maestro, Wawi Navarroza, Gina Osterloh, Gary-Ross Pastrana, Judy Freya Sibayan, Carlos Villa, Ryan Villamael, Eric Zamuco

Silverlens, New York

About

Curatorial Sections:

History and Identity

Patricia Perez Eustaquio

Norberto Roldan

Gina Osterloh

Identity

Poklong Anading

Lani Maestro

Judy Freya Sibayan

Eric Zamuco

The Body

Catalina Africa

Santiago Bose

Chati Coronel

Wawi Navarroza

Carlos Villa

Vessels

Stephanie Comilang

Kawayan de Guia

Gary-Ross Pastrana

Ryan Villamael

Shrines amasses iconographies familiar to the Filipino psyche: agimat (talisman), bululs (ancestral idols), and devotional indices like scapulars, hair, bone and litany set against tropical flora while hinting at a monsoon temperament. Prompted to think about environments that relate to higher powers, these visuals remain steadfast containers to the intricate grammar of a relational subjecthood that reckons with histories of colonial legacy and modernity’s pulse to identity. Embodied contexts of diaspora, itinerancy, and retreat mark the artists here in Shrines. Their works are poignant approaches to identity, where experiences with the body (here being the artists’ subjectivity and the artworks) engender the translation of belief systems that also ensoul distinct realms of personal history. While these artists and their works converge in a vernacular distinct to some Philippine cultures - à la “primitive mysticism and slick modernity”¹ - they circumvent such representative posturing in the palimpsests of experiences that initiate practices of attending to powers that be.

In the case of Shrines, it is a hope that such powers may be transcribed through the language of spirit. Let’s regard the practice of shrines as an enduring impulse that exteriorizes animating forces. Parallel and also prior to built institutions (temples and churches) and liturgies, shrines were approaches where “each person possessed and made in his house his own anitos, without fixed rite or ceremony.”² Built environments for spirits, and shrines are constructed as altars for ancestral reverence, or nooks set aside for elemental entities within proximity of one’s residence or business.

Stephanie Comilang’s sculptures hark to such domestic architectures prominent to mainland Southeast Asia that continue to shelter spirits. An Architecture of Belonging (Spaceship House) and Fake Plattenbau are speculative designs that connect memories and ideals of homes by Isan migrants in Berlin with the craft of a Thai architect and a traditional spirit-house artisan. Spirit houses are stable units of social spaces, anchored within a daily custom of sustenance and lodging. Their inception, adoption, and retirement are settled in ceremony, often arbitrated by elders or monks. In the case of the Isan women who are naturalised in Germany from the 1980s, spirit houses are the schema to which Comilang regarded their stories of migration and reconnection to Thailand. The local ecologies that spirit houses are attendant to are remote but the exigency to create communality in spaces becomes mobile, modular as the people who carry their home with them.

The virtue of relating designates a shrine. Offerings are arranged, picked from the bigger environment of produce, and prepared with intent. Contrary to the quote that such practices of anito reverence are “without fixed rite or ceremony,” protocols are observed according to affairs that are interior, domestic, vernacular. These systems participate in lineage and transform what is immediate.

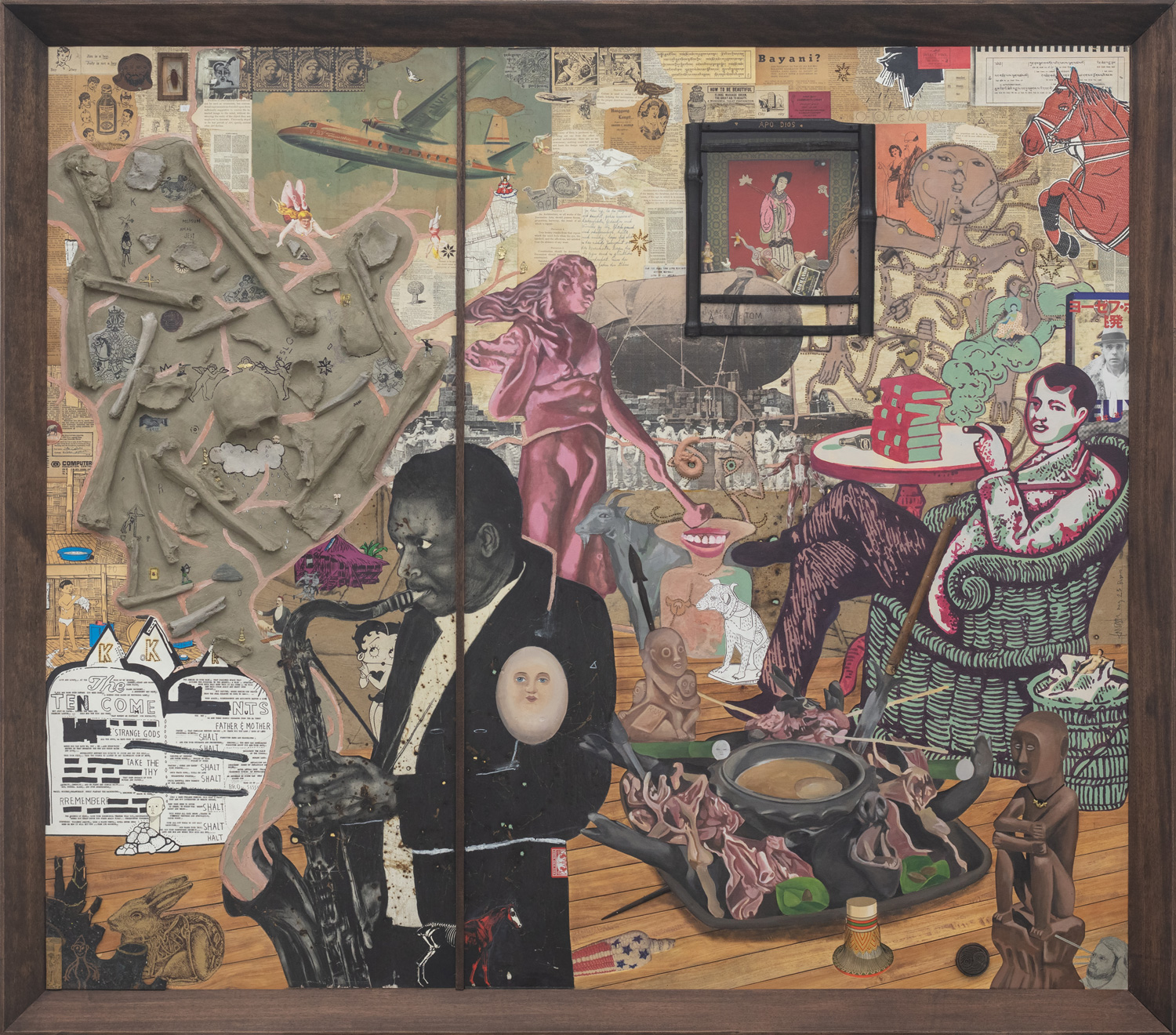

Carlos Villa wrote of the ceremonial aura of tributes in his auto-ethnographic essay³ that translates the artist's journey in Asian American history. The concept of atang is prevalent in his body of work as an artist, teacher and activist, where each gesture (including the recognition of every artwork in exhibitions he curated and participated in) is a memorial to the cultural and political worlds artists touch and struggle with. The work Group Grope Dream #1 (1982–1986) was conceived at a period when Villa emerged as a public intellectual orienting the discourse on multiculturalism in the Bay Area. This painting is situated in his body of work that reckons with the culturally-bound formalisms of painting and Villa’s ways of ritualizing materials.

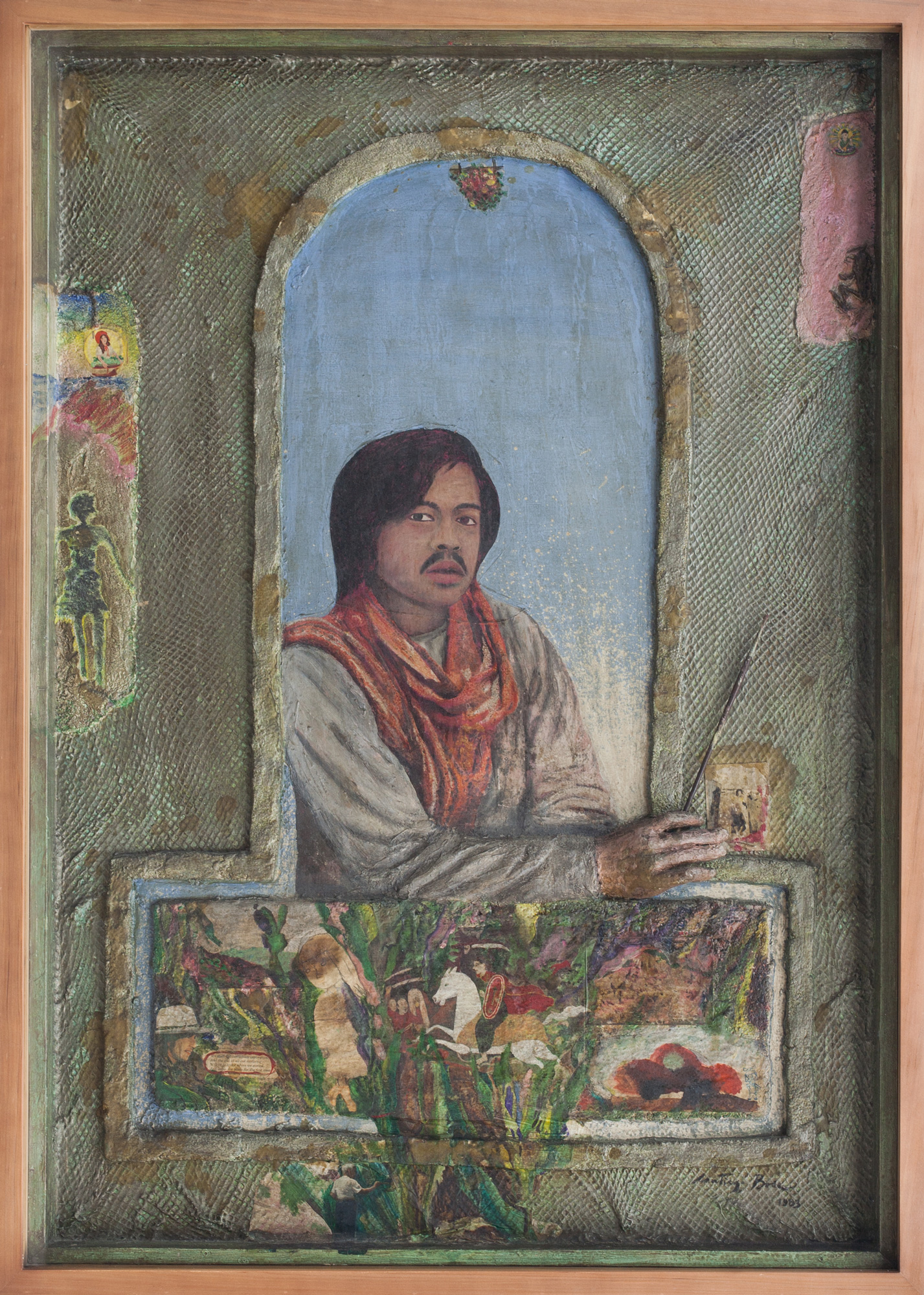

There is atang afforded to another elder in this exhibition. Santiago Bose, whose legacy of community cultivation and art practice springing from the north Cordillera region, mediated the vocabulary of indigenous cultures and the entanglement with colonial occupations. Eyes of Gauze plays on the irony that is in the undercurrent of Bose’s bricolage impulse, demonstrating “how textures and texts may generate not resolutions but doubts over doctrine or dogma.⁴” Relentless in the self-referentiality of the self-portrait as an artist (leaning on a painting, a paintbrush and photographic reference poised in hand), his gaze pierces as all-seeing. Bose is cavalier and comic as he frames himself as if around an altar, artist as god?, the punctum here is the space all around: gauze, an everyday mesh.

The critique on the artist embodied in pictorial rites as in Bose’s enshrinement of his artist identity extends to the critical processes in which creative forces are subjected to. As much as the body becomes a vessel to which worlds are conveyed and reforged, it also transcends the limitations in which its expression move around these worlds.

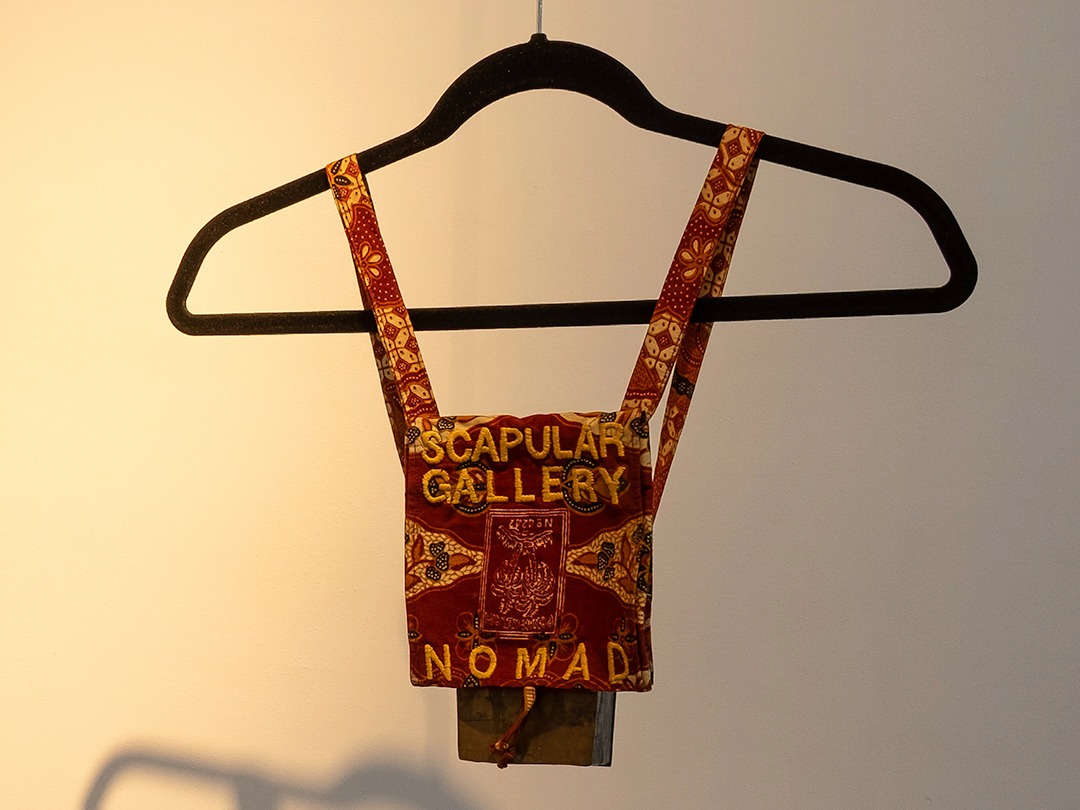

“Scapular Gallery Nomad” finds Judy Freya Sibayan channeling the operations that artwork and artworld weather. These practices are carried from one body (a commissioned artist) to another (Sibayan’s), performing a moving shrine. In 1994 and from 1997–2002, Sibayan acted the roles of a gallery managing a work - curator, writer, dealer, as she wore these exhibitions like the grace garment this project is named after. Art hoisted around her neck, the mechanism of institutions to exhibit, make meaning and enable commerce were enabled when the scapular was acknowledged. Corpus takes on another substance as Sibayan gathers an archive: the textual and the performative communize with the objects that record these modular galleries. The reimagination of institutions through the agency of the artist is a devotional one, influenced by the enduring reverence associated by the Carmelite Brown Scapular. Scapular Gallery Nomad #1 (Artwork and Gallery are one and the same) and Scapular Gallery #2 hark to other forms of piety: the sacred heart and the Tibetan Buddhist gau.

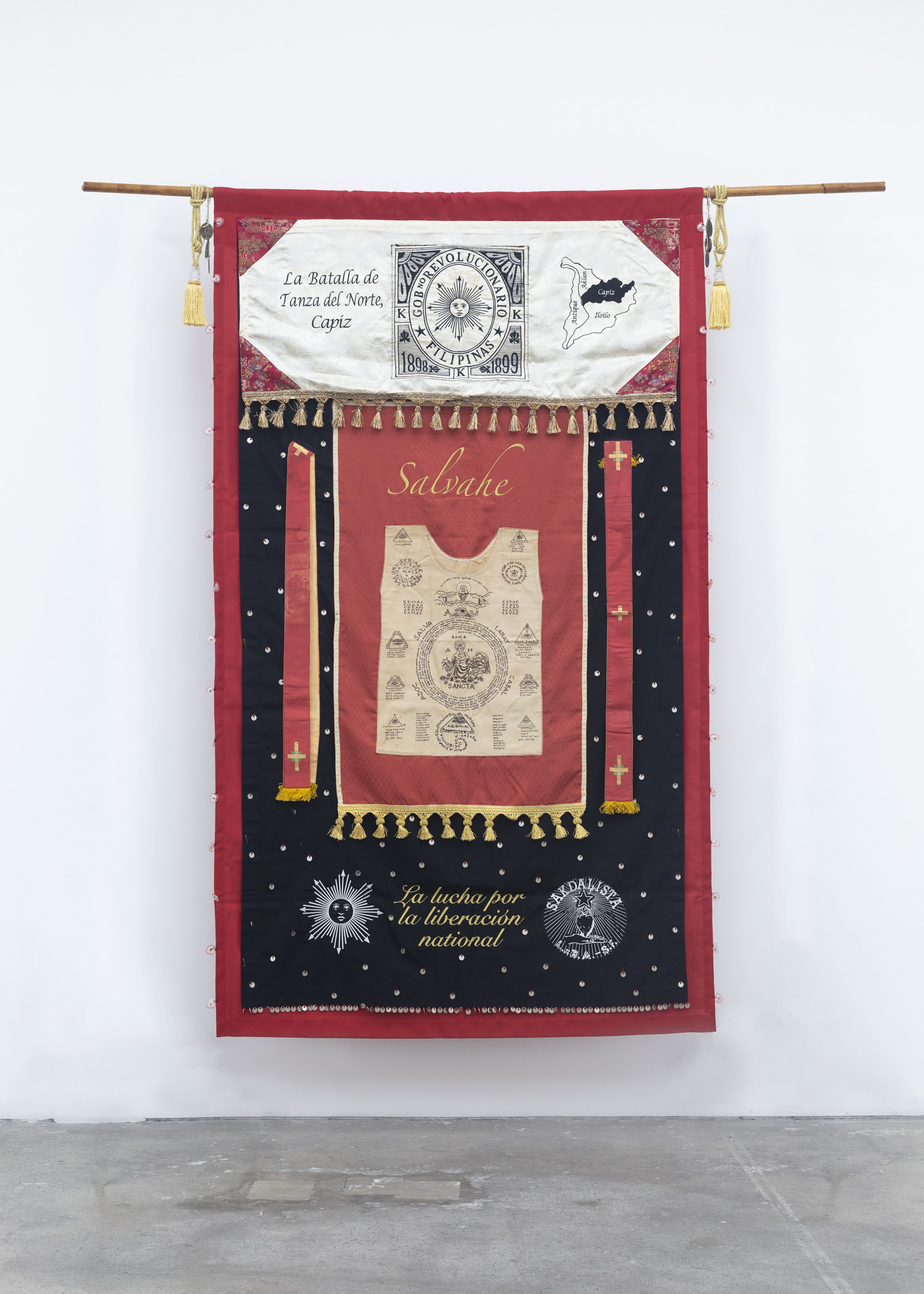

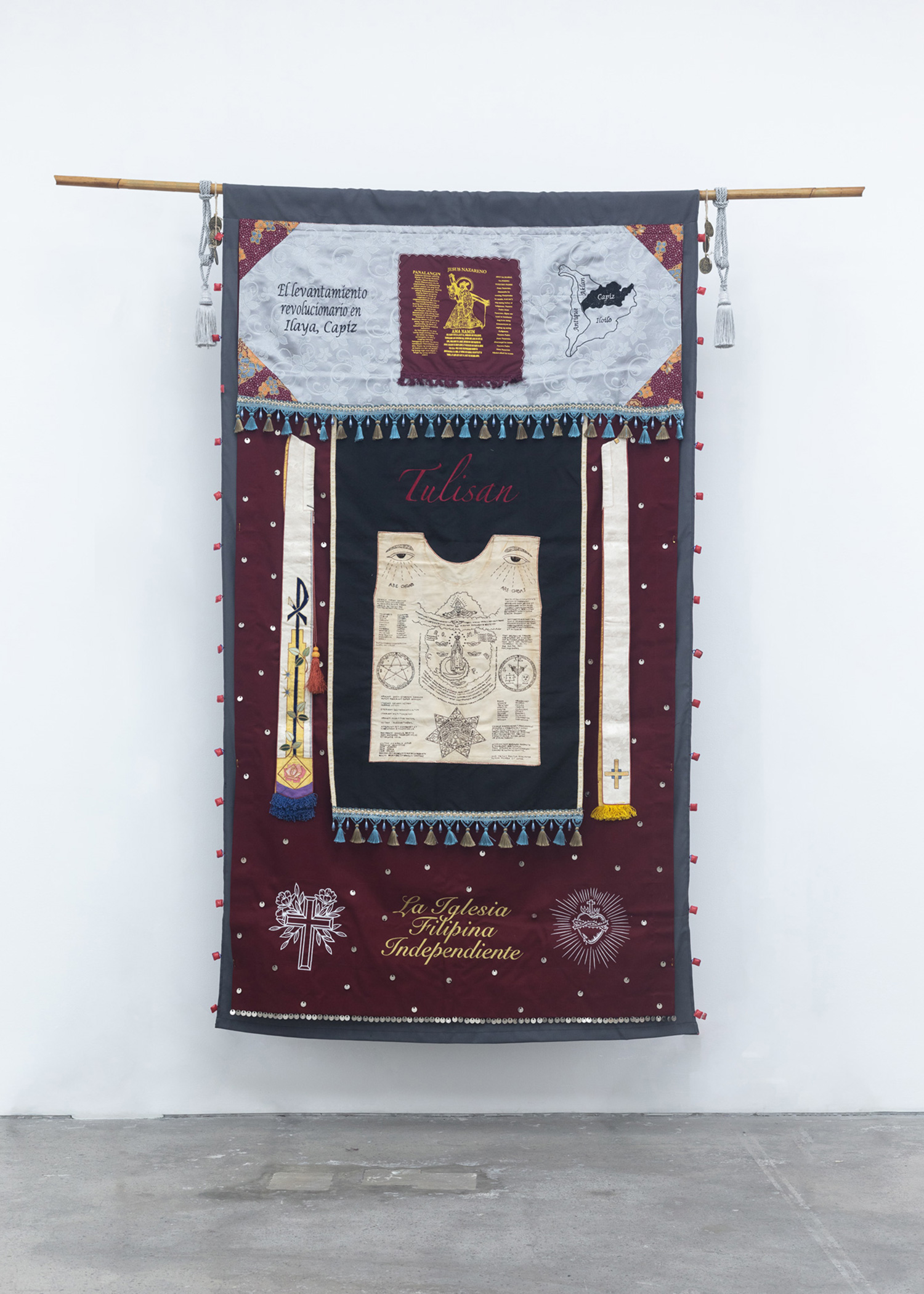

Spirit is material and histories are ensouled in the garb and things one wears to carry expanded realms and invigorate authority beyond the corporeal. For instance, the symbolism of these objects and icons begets an annexed lineage of belief systems that served resistance movements. Norberto Roldan memorializes folk histories of local organizing and the apocryphal accounts of revolutionaries being invigorated, if not infallible, as they bore anting-anting. At the center of the tapestries are the war vests beneath “Tulisan” and “Salvahe,” reputations affixed by colonial governance to their “natives.” Bandits, they misbehaved not only in arms but also in the transformation of church iconography in orasyones - rituals and prayers casting amulets to their talismanic function of garnering powers of protection and combative defense. The work La Iglesia Filipina Independiente harks to its Aglipayan Church namesake, highlighting this entirely-Filipino organization conceived as part of the opposition to Spain. The success of skirmish in Capiz was owed to the indefatigable daring of the rebels with La Lucha por a Liberacion National, eliciting a rallying catalyst emboldened by a syncretic belief system.

Syncretism is a vocabulary familiar to cultures directly reckoning with colonial occupations, much like the notions that multiculturalism engender at a certain period in global discourse. While these discursive opportunities are being re-oriented to amplify indigenous knowledges, we find that the integration of systems that localize ceremony, while taking from imperialist lexicon, is an insurgent’s response. The impulse to order the world, that which is immanent and immediate, is the agency of spirit setting the past in motion.

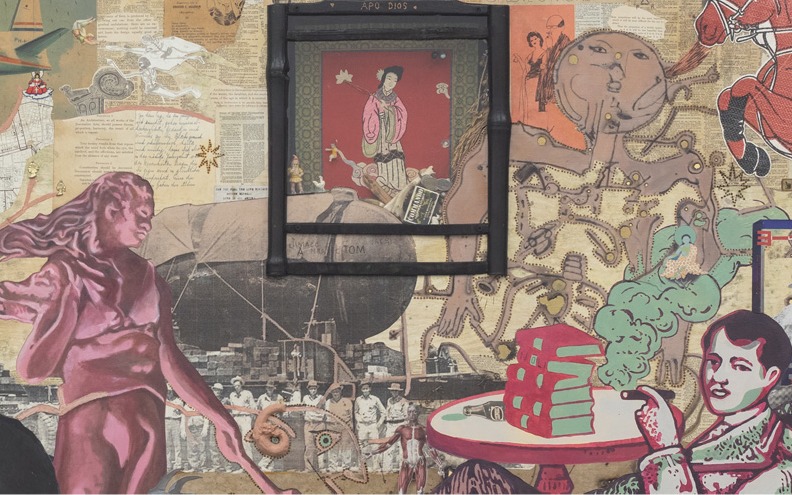

Assemblage is the subjective grammar that sutures wounds of struggles and materializes the sources emancipating communities across time. the great gasp “HUKLIT” a time for abstinence and offering places icons of modernity and tradition in strata: jazz, liberation personalities, cargo carriers, alongside ancestral figures and skeletal remains are framed about loose grids, heeding to the practice of securing ritual pieces in boxes. The frame is primed with newspaper clippings and cut-outs, as classical prints and art school citations are posted as relief, collage and painting by Kawayan de Guia. Like a scholar’s shrine operating on the transversality of his sources, his works are built from maneuvering the syntax of his material collections and collective recollection.

The world may be organized in visual stability as it is in obscurity. What remains are motions in which symbolism becomes processed - symbols are learned, and their visibility contingent on the conditions they take form from. The 1963 work of Fernando Amorosolo is the ritual stage from which Death of Magellan (After Amorsolo) commences; the integrity of the image (and consequently the subject) is deconstructed and translated through the constitution of painting, photograph and tapestry. Patricia Perez Eustaquio materializes the rhizomatic structures of information and public history, gendered and communal labor in medium, the invisible threads of translation, and the scale and fallibility of image.

Devotions are processes, much like the imagery and object deployed to aid supplications and acts of reverence. Visuality may take the primary stage of ritualizing the engagement with spirit as how iconography ensues from materializing what is omnipresent. Invocations like the orasyones, however, are constituents of symbolism as they evoke occurrences that reach for the pervasive divine.

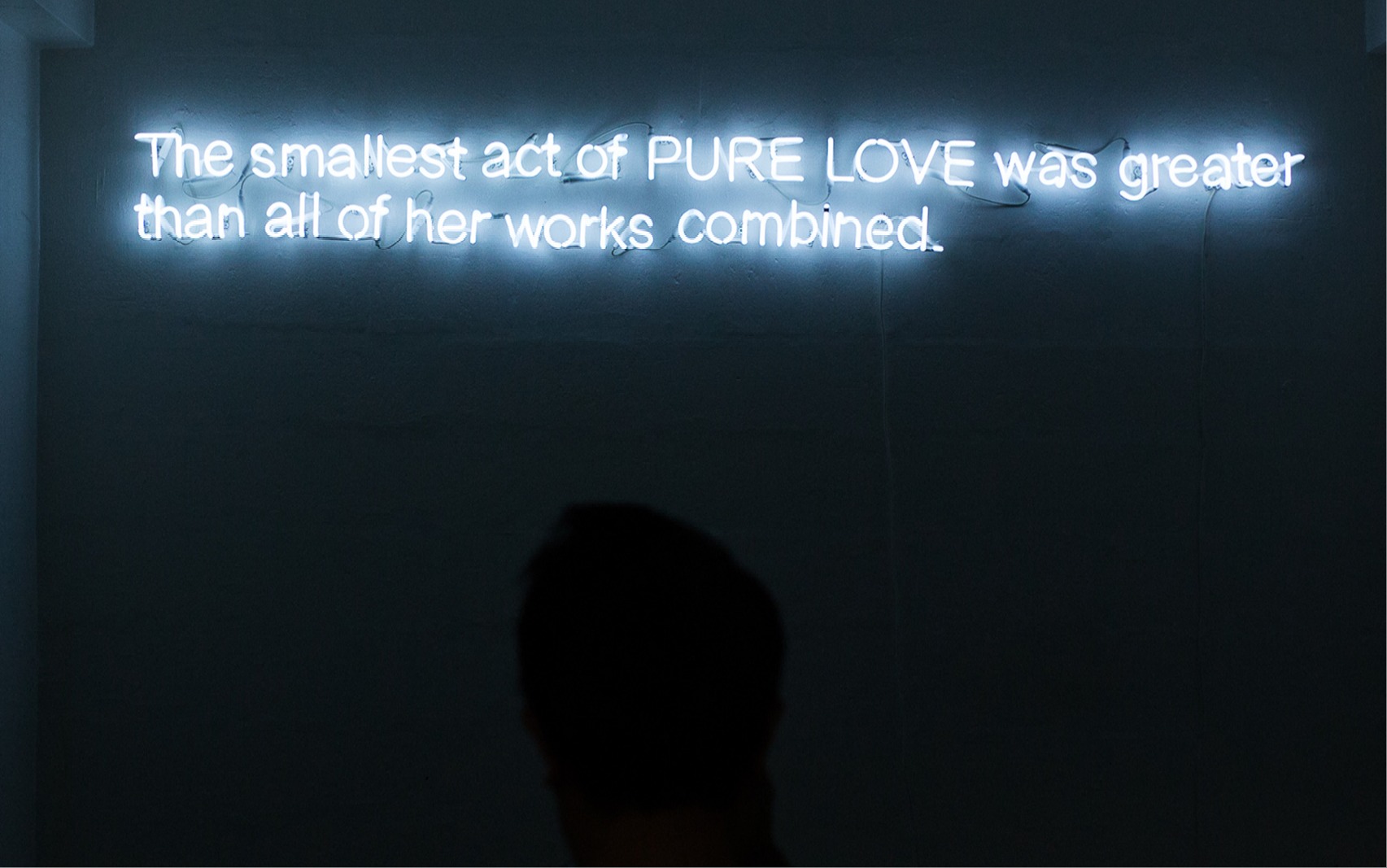

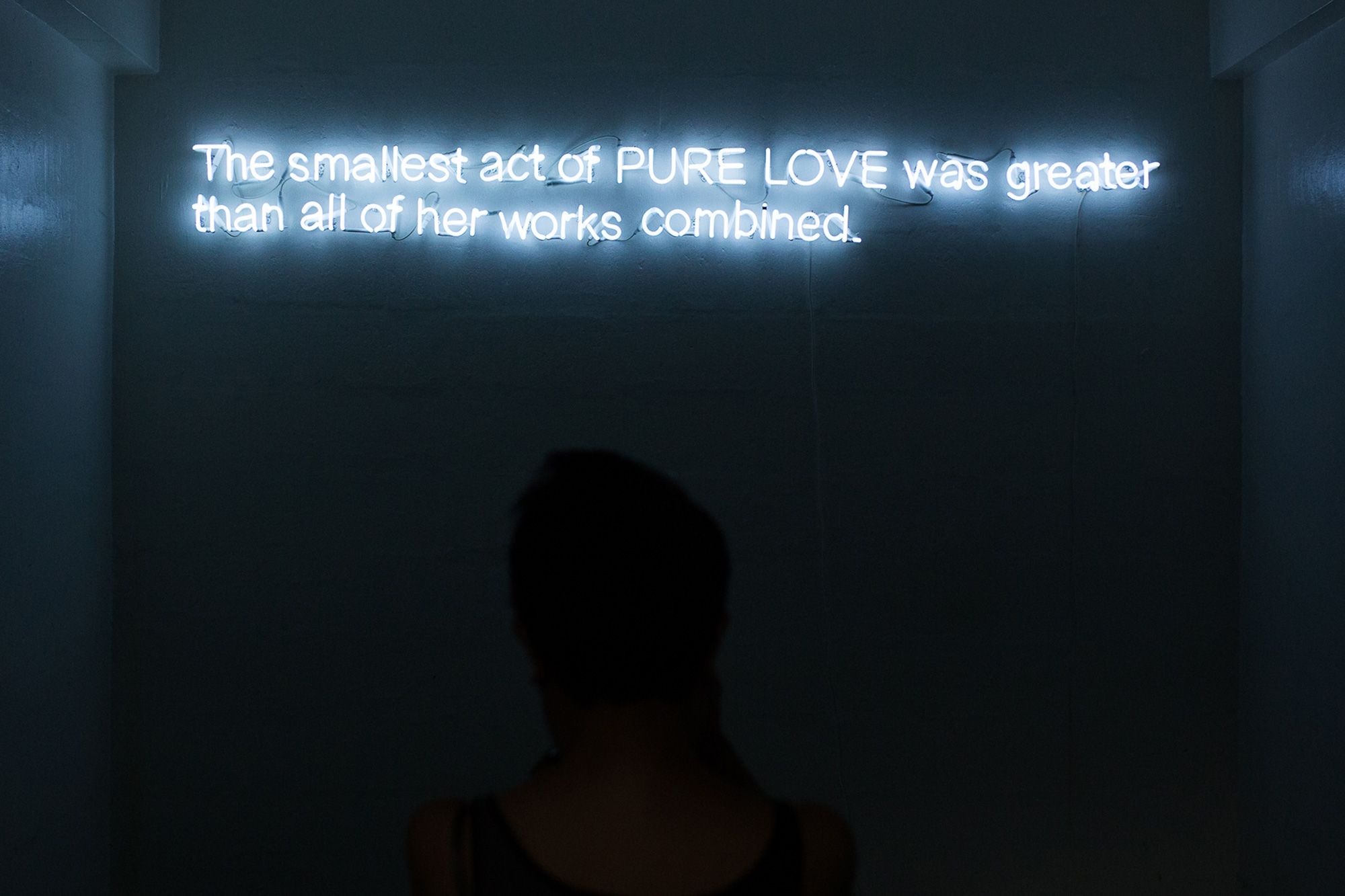

her by Lani Maestro encapsulates the power of agape in brevity: “the smallest act of pure love was greater than all of her works combined.” A rendition from an account of St. Therese of Liseux, this work illuminates a spiritual course of the “little way” where actualizing transcendence is rarely a singular, monolithic command but a ritualized everyday of small deeds that overcome the limitations of the self. Maestro’s practice pivots in poetic gestures, her works coming into form through intentional conversations between space and her memorialization of people and human experience.

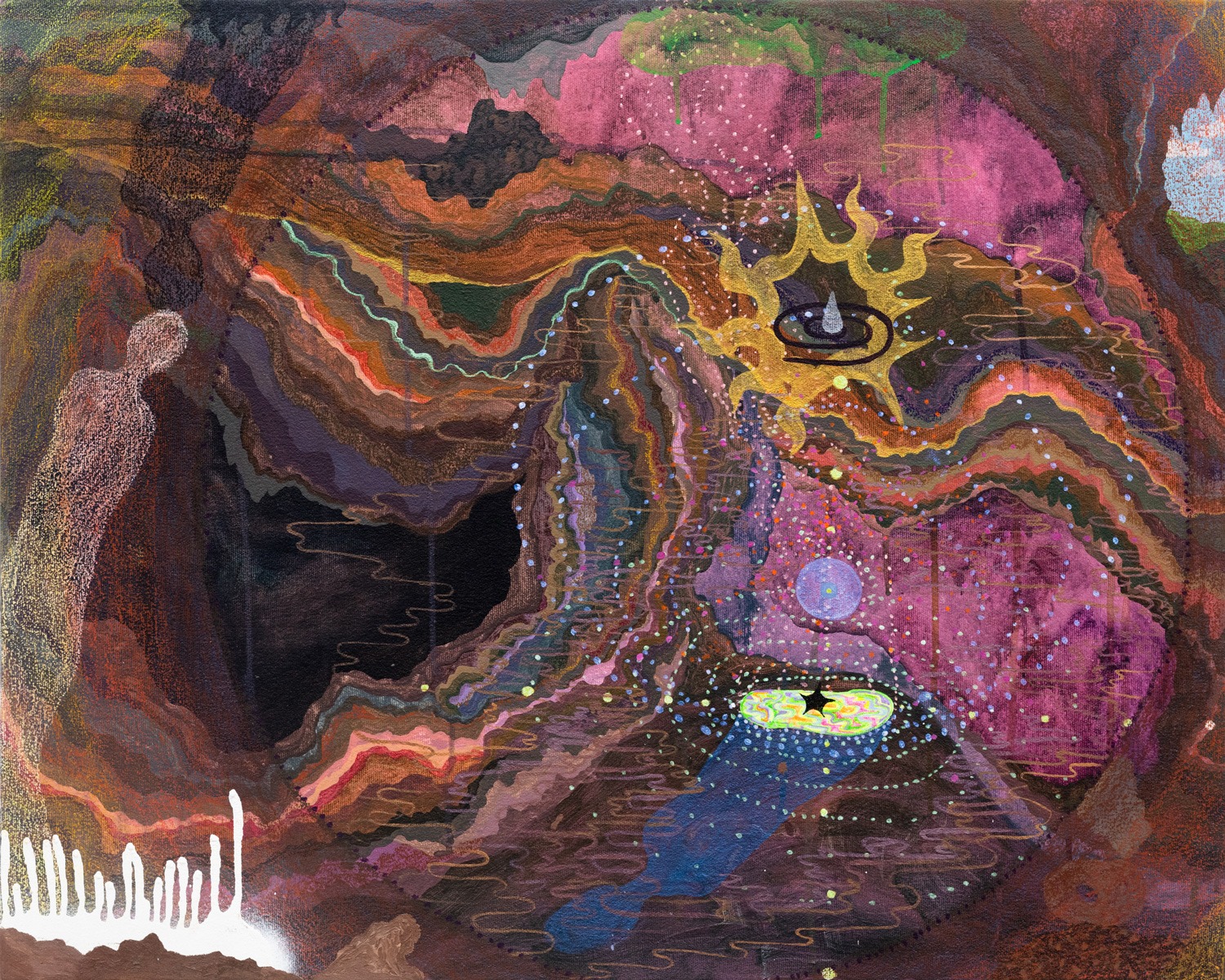

Invocations that necessitate deep methods often rely on a flow state that met the gradual accumulation of “small acts.” Heeding the cycles of creativity where gestation, transformation, completion and composting play equivalent roles, Chati Coronel paints with time more than figurative totality. In a trance-like state, she meets the stages of her painting and daimon layer by layer. Asterisk and Of Fireworks and Halos emerge like as it would a sacrament: a base color or image sets the scene, and a textual rite proceeds over that foundation, and layers of figures and silhouettes eclipse one over the other, until the apparitions surface in completion.

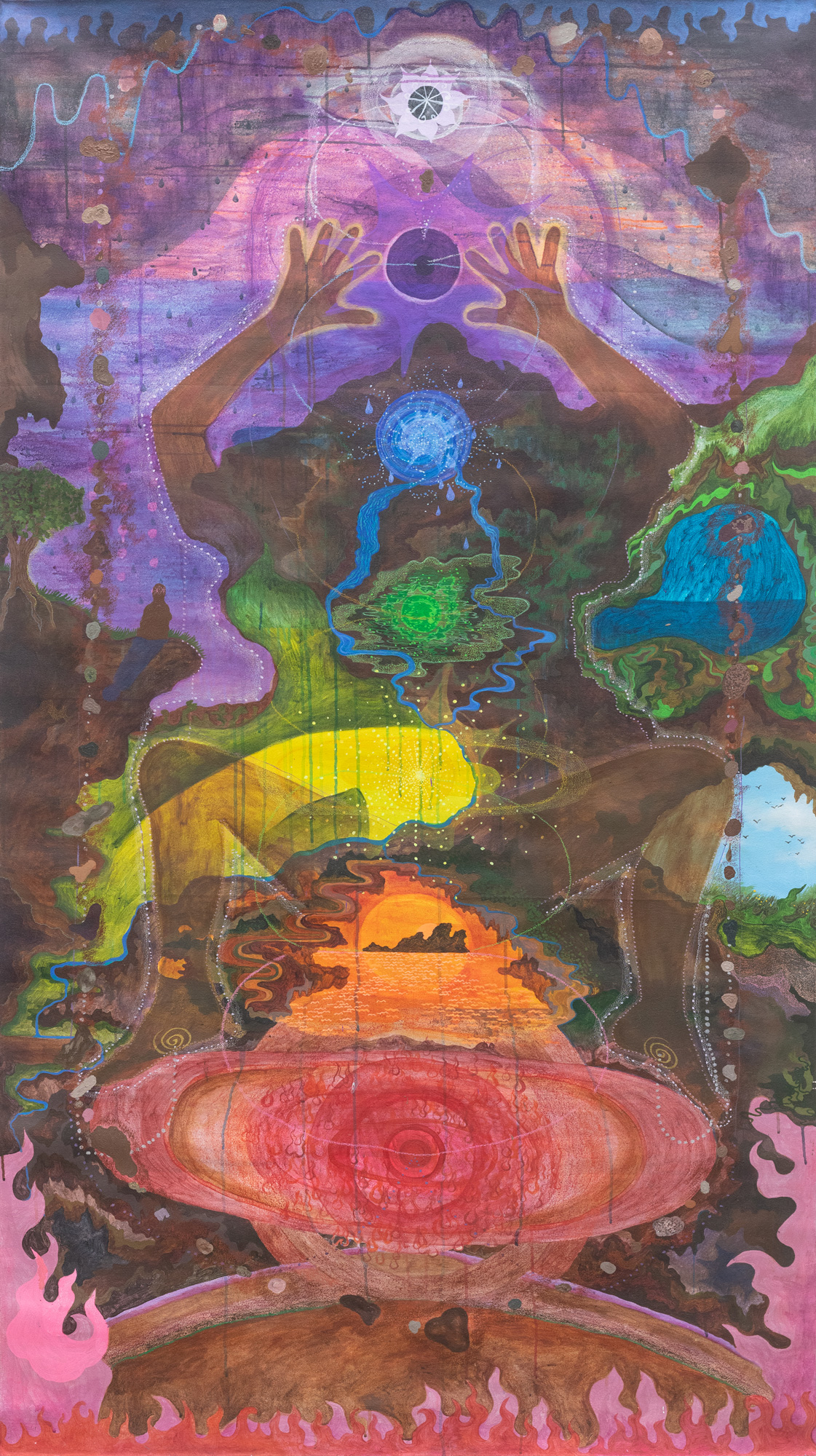

The manner in which matter eludes form is also present in Catalina Africa’s paintings, where spirit operating through material and subject shapes the images in humus/human. Toeing past painterly thresholds, core consciousness and earthbody/dream portal bleed into elemental landscapes. Perception extends from the natural world, bridged by humans stepping up to their portal qualities. The rule of correspondence is at work: what is inside is also outside, that which moves above also activates the same way in what is underneath.

Portals are casted when the limitations of the body are pressed against its edges. I Want To Live A Thousand More Years (Self- Portrait After Dengue, with tropical plants and fake flowers) steps forward out of highly charged occasions that opens Wawi Navarroza past the boundaries of her person and into numinous interiority. In her photography, the imaginary of the tropical gothic translates as a site of endless bloom amidst the turmoil of becoming. Tracking the scripts of archetype and stormy footing that begets self-actualization is the arena where decay, artifice, exaltation and renewal mingle and wed. The only way to put this to the fore is certainly by the offering of the self: portraits of the natural (and under-) world itself, as seen in the jubilation of New Pleasures and Brave New World.

The talismanic body as an interface between worlds are what many works in Shrines convey. Negotiating with historical and geopolitical forces, the body remains the emanating center where spirit incarnates. To ritualize the world in order to conceive and transact with its spirits, is to press against the corporeal edges of one’s own altar that intercede for the atonement from societal limitations.

Gina Osterloh proposes critical lexical approaches in witnessing the body as a conduit to other bodies and their histories. In pictorial strategies that interrupt the conventions of portraiture, she interrogates the rhetoric of representation that encumbers identification. Looking Back bears the question of illegibility of her heritage, but also pulls at that cord. She turns away to turn toward. In Rapture, the figure gives homage, signaling surrender of one’s individuality to a force field that stitches the lines of subjectivity (hers, her mother’s) and offering power to the tapestry that envelopes narrative of passage, lineages across time and country. These gestures vindicate the heterogeneity of selfhood by deferring the cultural determination of the portrait. The photo tableau is a shrine where the body rehearses to touch a space that is immaterial.

Eclipsed by flares refracted from the angling mirrors towards the sun, the visage of the subjects in Anonymity by Poklong Anading eludes recognition. Identity slips away from reductive representation, and the stage of the photographs are not in familiar city scenes but the mirrored gaze between beholder and image. In this series, Anading makes legible the circumstances of illegibility. The background is the field of vision, marking the moment of looking and being looked at. In one image’s foreground, shadows crowd around the subject, suggesting a crowd of onlookers. Evidently, deterministic markers are resisted; and in lieu of face, the punctum of obscurity is what illuminates the measure of individuation. The self recognizes itself in its effacement, as with a portal where the body enters in reciprocal witness.

Withholding the perimeters of matter, a space extends. Recognizing our cohabitation with spirits, there emerges a locality that is elastic, a passage to the interiors of selfhood. As a physical framework, shrines materialize that which is immanent. As an environment, these portals carry us across time like a convoy to the past, precipitating a contemporaneous future that preserves the animation of the world.

The works of Eric Zamuco usher us to objects, or processes that make and undo things, as meditation and physical mediations on the ubiquitous and, sometimes, disorderly divine. Made out of food containers, God To Go forms a candelabra, hinting at the critique towards the smorgasbord of belief systems packaged towards individualism. Hinging on the axis of the banality of everyday and the prospect of providence in the physical relationship to things, Zamuco attunes to found objects of no inherent spiritual essence. Kagandahang loob speculates if spirituality arranges itself, as with the totemic structure of these squashed traffic cones, charred wood, images of firetree flowers and cursive medical shorthand. The conditions of identity may make transcendence elusive, but between the commonplace and the participation of one’s sovereignty, faith may be consummated.

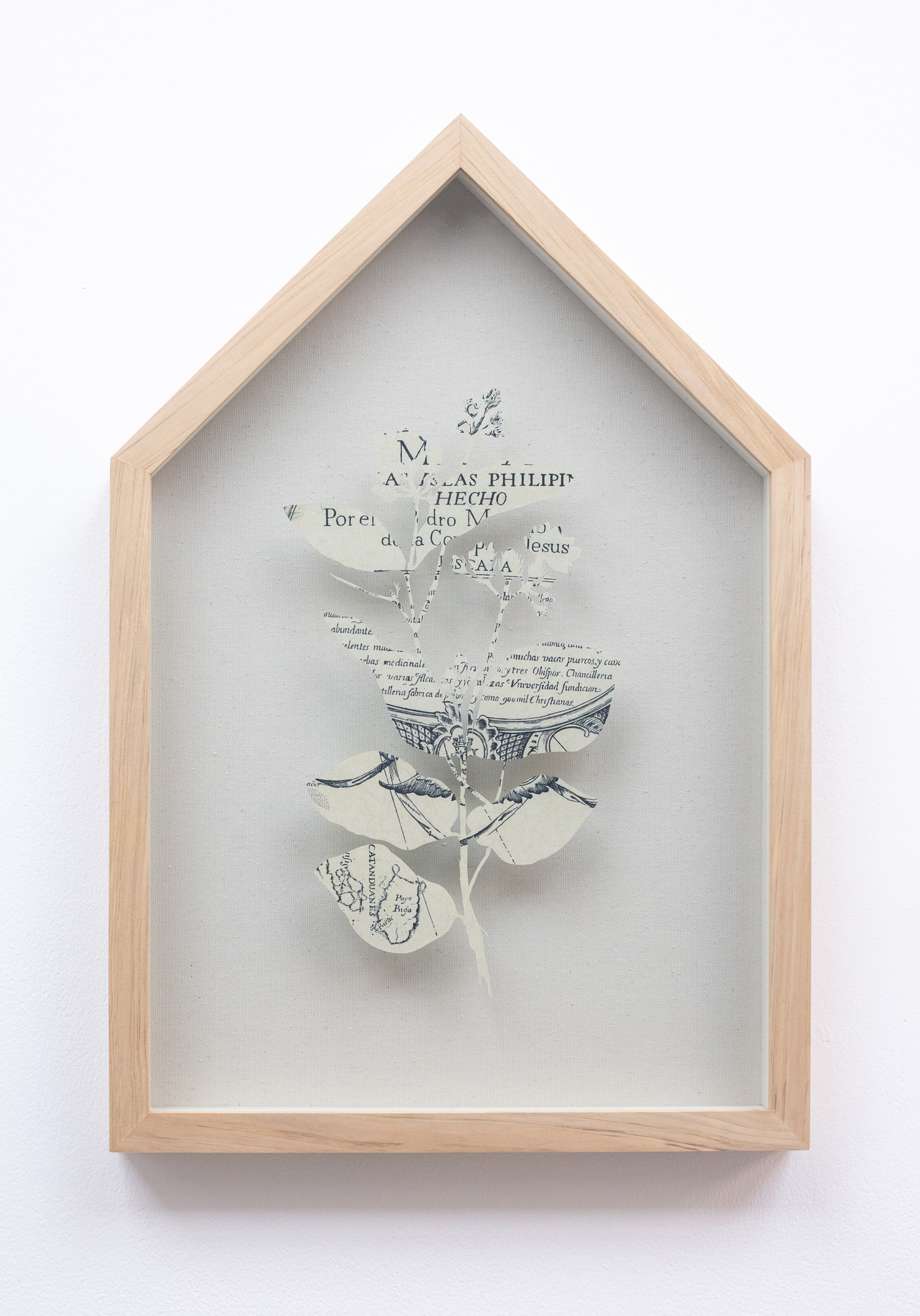

What moves the world is instilled in objects - artifacts that carry gestures of unmaking and re-casting. Ryan Villamael simulates botanical conservation in his terrarium sculptures, using the ploy of colonial plant transportation and exhibition against itself with his use of archival maps to incise the flora into form. Craft appoints a direct line to incarnation in his paper sculptures, exposing the sovereign capacity of configuring the world by the finesse of the hand. Seized in a vitrine, Pulo is an oasis of an island that safeguards a vision of an indigenous loci. Cut from the histories of colonial nomenclature so that their nativity may be cultivated back to consciousness, Ixora manila Blanco, Piper betle L., Jasmin sambac and Oryza sativa L. take pages out of maps as relic to their perpetuity.

A speculative animism is proposed by Gary Ross Pastrana, drawing from sources of science fiction and ethnic cultures to prospect the future of idols and scenography. (Eidolon IV) Lot- 01 Provisional Objects Series touches on the apparitional quality when transacting with thingliness. The imaginary takes on shifting vessels, according to the circumstances from which they are conceived. Commissioning a bulul maker, Pastrana envisions from adaptations of these spectral entities a bankable artifact of a robotic beast stalking humankind. Collective worship shapes a place, extending beyond the boundaries of shrines. The atmosphere of devotion is invoked Untitled I (yellow) and Untitled II (white), inquiring on the portability of offerings so that they may be transported to anoint a space.

In order to face the divine, one goes through forms of intercessions. Shrine to shrine, the works animate this mediation through ritual and objects, crystallizing particular expressions of attending to the transcendent: through symbol and matter, in brevity and mystery, under layered patinas of incantation or synthesis of the polyphony of prayers, by way of the artist as a supplicant for spirit to be within reach.

– Siddharta Perez

¹Nick Joaquin, The Woman Who Had Two Navels (Ermita: Solidaridad Publishing House, 1972), 27. This enticing qualifier sets the tone for plantation heir Macho Escobar’s attraction towards Mañilenos/ Mañilenas.

²This quote by Antonio Morga’s 1609 report was excerpted as an annotation to the Babaylan in history from colonial reports in Grace Nono’s Song of the Babaylan: Living Voices, Medicines, Spiritualities of Philippine Ritualist-Oralist-Healers (Quezon City: Institute of Spirituality in Asia, 2013), 18.

³“(60 Forms of) Atang Payback and Tribute (In Filipino)” (1995) by Carlos Villa is part of the resources gathered by the author in a 2019 research project on Villa’s symposia and curriculum series Worlds in Collision.

⁴Patrick Flores describes Bose’s creative instinct to assemble and codify different sources in the recently concluded exhibition Spirited Traces in Silverlens Manila.

Video

History and Identity

Identity

Edition 1- SOLD

The Body

Vessels

Lot- 01 Provisional Objects Series